Teacher ed grows in many ways

Program adds students, expands support for current and future educators

What can you add to 688 to total 958?

In Central Michigan University’s teacher education programs, the answer is one year: From fall 2017 to fall 2018, admittance and enrollment in teacher ed grew from 688 students to 958, a 39% increase.

To Betty Kirby, acting dean of CMU’s College of Education and Human Services, the explanation is simple.

“CMU is the place to come for excellent teacher preparation,” she said, “and now is a great time to become a teacher.”

Support in the marketplace

Kirby said the Michigan market for highly qualified teachers is phenomenal. Employers are offering signing bonuses and snapping up teachers through early release from student teaching. But don’t just take her word for it:

- “We are feeling the teacher shortage. This year alone we have had at least three teachers be released from student teaching early to take over their own classroom.” — Linda Boyd, assistant superintendent of Mount Pleasant Public Schools.

- “This year, we released a student teacher a few days early to have her cover a long-term substitute position in the building. We also released a student teacher a week or so early to be able to be hired for an interventionist position. The need for highly trained teachers in Michigan is immense.” — CMU alum Mary Lang, principal of North Godwin Elementary near Grand Rapids, Michigan.

- “This past fall, we needed to add a kindergarten section. Abbie Kowalski, a CMU student teacher, was having great success in one of our early elementary classes. We reached out to her and were able to plan for her transition into the new section under the early-release guidelines.” — Justin Gluesing, assistant superintendent for human resources and labor relations at Alpena Public Schools in northern lower Michigan.

- "There is a definite teacher shortage and substitute teacher shortage in the West Michigan area. In this past year, four of our CMU special education majors were hired as long-term substitute teachers. Our regional principals have shared that they appreciate CMU student teachers being well prepared in the foundations of teaching." — Cindy and Tim Hughes, university coordinators in West Michigan with CMU's Center for Clinical Experiences.

Numbers back up the testimonials. The jobs page on the Michigan Association of Secondary School Principals website lists more than 400 open positions.

Even as some schools and districts attract plenty of applicants, others struggle to fill any openings. Special education candidates, for example, are scarce and highly prized, and urban and rural schools see some of the worst shortages.

Some claim Michigan has more teachers than it needs, citing large numbers of qualified teachers not teaching in the state. Kirby said those figures are misleading because they include tens of thousands of people not in the teaching job market: retirees, administrators, specialists and others who use their education degrees in other fields.

Support from the start

CMU’s Professional Education Unit prepares students in more than 20 majors across five CMU colleges to become elementary and secondary teachers.

Teaching is one of the first jobs children see up close. As they start thinking about careers, it’s a popular choice.

For some it will become a passion, and by the time they’re in high school CMU’s teacher ed programs are ready to welcome them.

Each November, the Students Educating Every Child Conference brings to campus 250-300 high school juniors and seniors for a day of exploring education as a career and learning what CMU has to offer.

The invitees are students taking introductory teaching courses at career and technical education centers statewide.

If they later enroll in teacher ed at CMU, students who pass those high school classes with a B or higher can earn three college credits, equivalent to passing Central’s Introduction to Teaching course, EDU 107, said Shannon Ebner-Buning, assistant director of professional education.

Support over the rough spots

No one says teaching is easy, but CMU says you don’t have to face it alone or unprepared.

In response to morale issues like tight budgets and long hours, and because retention is a challenge in the first few years of teaching, Central addresses future teachers’ social and emotional well-being.

“We included a session on self-care at both the fall 2018 and spring 2019 Teacher Candidate Conference,” said Jillian Davidson, director of the Center for Clinical Experiences. “It was extremely popular with candidates, so much so that oftentimes there were not enough seats for all the candidates who wished to attend.”

More self-care opportunities are in development, including a mentoring program for special education alumni that includes a burnout prevention component, said counseling and special education faculty member Brandi Ansley, who facilitates the self-care sessions at the Teacher Candidate Conference.

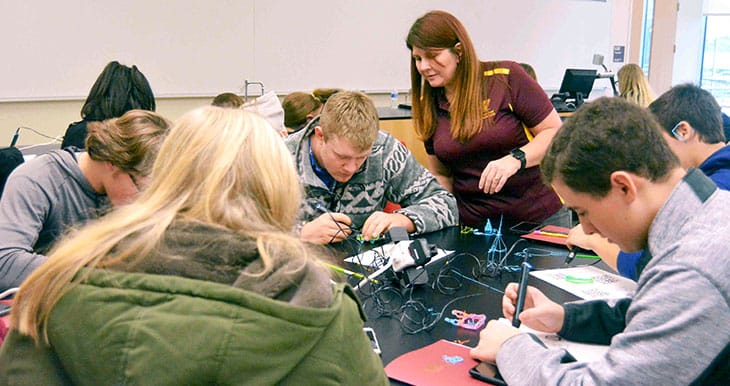

Teacher candidates also build support networks with professionals through classroom partnerships such as CMU’s innovative co-teaching program.

And of course many faculty provide support long after graduation.

“CMU is still helping to develop me as a person and educator,” said Jeremy Winsor, who graduated in 2006 and teaches earth science, biology and environmental science at Fulton Middle School-High School in mid-Michigan.

He cited two of his former instructors — Troy Hicks and Wilene Pangle — for helping him to find his voice in teaching and to embrace “inquiry education” and the value of exploration.

Winsor is one of 10 Michigan Department of Education 2019-20 Regional Teachers of the Year (as is fellow CMU alum Rachal Gustafson, a special education teacher at Rapid River Public Schools in the Upper Peninsula).

Support through professional development

To stay certified in Michigan, teachers must keep learning, often by taking courses at their own expense.

This summer, CMU hosts its first three-day language instruction institute for K-6 teachers, offering 21 hours’ worth of continuing education and follow-up sessions throughout the year. With support from the Meemic Foundation and an anonymous donor, the institute not only is free of charge, it will pay $150 stipends to its 32 attendees.

That tells teachers their time as professionals has worth, said Betsy VanDeusen, teacher education faculty member and director of the Literacy Center at CMU.

The institute is July 30-Aug. 1, and VanDeusen plans to make it an annual event.

Central also hosts occasional informal “dinner and dialogue” educational sessions where Mount Pleasant schoolteachers and CMU teacher ed students can network.

The events lift up the teachers as valued partners, VanDeusen said. That increases job satisfaction, builds understanding between CMU and its alumni in the field, and helps meet the ultimate goal.

“Everything we do, we’re ultimately thinking of students in the classroom,” she said.