Sleuthing out new sources of lithium

Soil contains clues pointing to critical car battery element

Clues in the soil could point industry to new sources of an element critical to moving the world to electric vehicles.

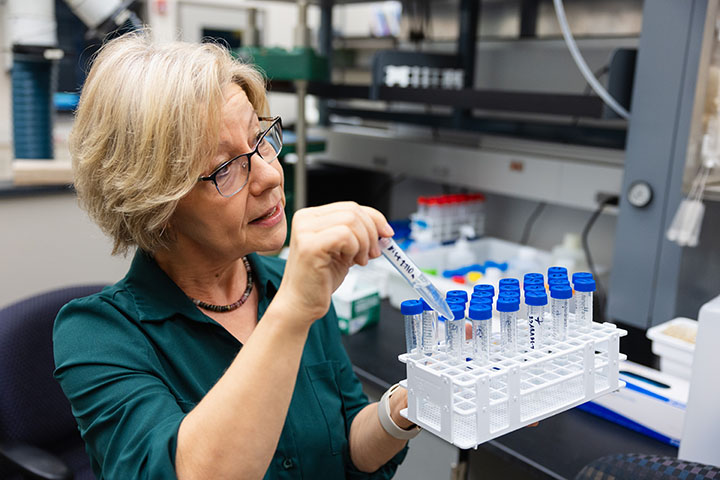

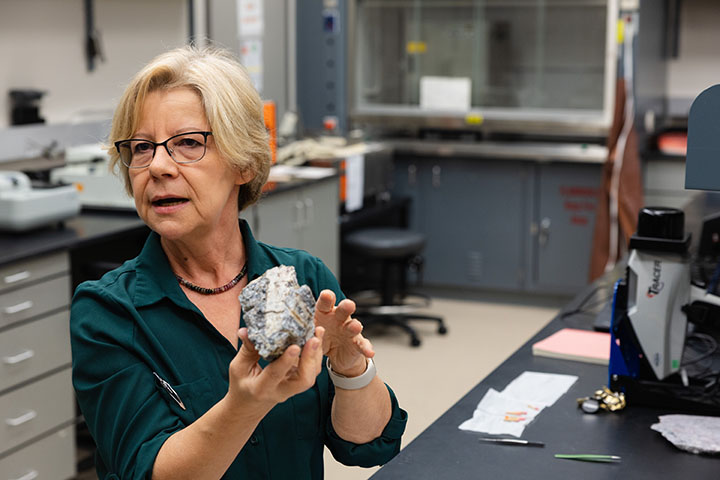

In a pilot project led by Mona-Liza Sirbescu, a geology professor in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, researchers are examining soil and tree samples for elements that point to the location of lithium.

Sirbescu and a team of CMU students gathered the samples first in 2022 and again in 2023 in Wisconsin near the Michigan border. They brought them back to Mount Pleasant for a complete analysis.

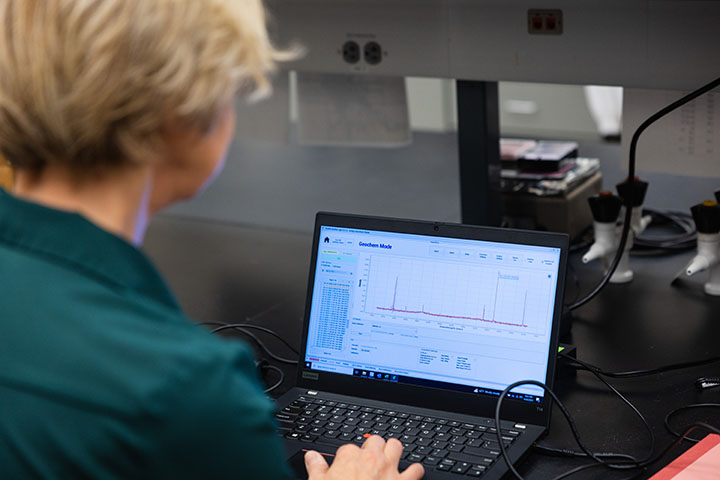

The process begins by pulverizing the rock and soil and then dissolving them in acid. Afterward, the samples are analyzed for lithium and the elements associated with lithium. Researchers hope to use these elements to pinpoint the location and quantity of lithium in the bedrock.

Lithium is in high demand today thanks to the rise in demand for electric cars. To address this demand, private enterprises are looking for new sources. Sirbescu received grant funding from one such enterprise last year to start her project.

Understanding lithium’s relationship with magma is crucial. As magma solidifies, it forms crystals that exclude lithium and related elements. These excluded elements travel through creases in the rock until they solidify and form their own kinds of crystals.

Some of those elements are transferred from the bedrock to the soil on top of it, including lithium. Portable equipment can detect and quantify these elements, which are heavier than lithium.

Samples collected by Sirbescu’s team contain some of those elements. Higher concentrations of those elements suggest higher concentrations of lithium. Where the concentrations decline, concentrations of lithium also decline. She hopes to return to Wisconsin next year with portable equipment.

In some places, the soil is thick enough to block detection of the chemical signature, she said. So, they turned to the trees for a solution.

Some of the companion elements dissolve in water, and the roots of big trees that reach down into the soil can draw those elements into their trunks. Sirbescu sampled the trees – using a technique designed by forestry experts that doesn’t create harm – in hopes that they could see signs of lithium.

Raw field samples might only tell part of the story. Sirbescu said she plans to dissolve the tree samples to get a full picture of what the samples contain.

The trees – and soil – were part of a former logging operation. The property is considered pristine, and a priority is to learn how to explore for lithium and mine it sustainably, with minimal environmental impact, she said.

One potential benefit is replicating the project in similar environments with comparable vegetation and temperate climates, she said – particularly those climates with cold, wet winters.