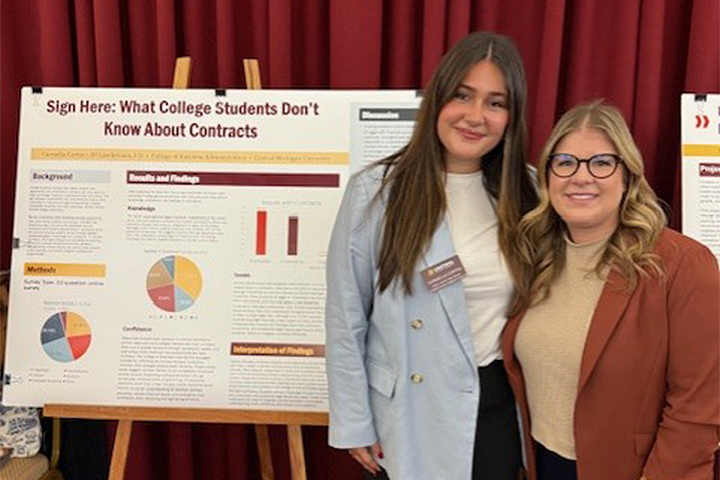

The partnership behind a successful honors capstone

A CMU student and faculty advisor reflect on trust, challenge, and academic growth

For many students in Central Michigan University’s Honors Program, the capstone project looms quietly in the background for years—a requirement that feels distant at first, then increasingly real.

For Carmella Cortes, a finance major with double minors in information systems and legal studies from Clarkston, Mich., the honors capstone became a way to connect her undergraduate studies and her future goals.

“I wanted to treat it like the bridge between Central and then beyond—whatever I was hoping to pursue,” she said. “I didn’t want it to be some offhand thing to get out of the way, or to check off a box on the list.”

Choosing a direction—and an advisor

Honors capstone projects offer students significant freedom, which Cortes describes as both empowering and challenging.

“They really give you a lot of freedom, which I appreciated,” she said. “Definitely a blessing and a curse. A lot of freedom, but minimal direction.”

With plans to attend law school after graduation, Cortes knew she wanted a topic that blended her business background with legal studies. Selecting a faculty advisor became the next step. She approached Jill Lauderman, a business law faculty member who had taught her in BLR 202: Legal Environment of Business.

“I loved her class and I loved her approach,” Cortes said. “I also really value female faculty and women in leadership, so I definitely wanted a woman faculty member to help me with this.”

For Lauderman, serving as an honors capstone advisor was a new experience, but she saw the potential for a meaningful collaboration.

“I knew it was going to be a great journey,” Lauderman said. “Carmella is really easy to work with, so that made it all the more beneficial as we went forward.”

From a real-life moment to a research question

The project’s focus emerged from an everyday experience: signing a lease.

“She had just signed her lease agreement for her apartment,” Lauderman said. “She said, ‘I just signed this huge contract. It’s like 20 pages long.’”

As the two reviewed the lease together, Cortes began to see how unfamiliar language could obscure important details.

“There was one section they phrased very broadly,” Cortes said. “They were able to enter the apartment if and whenever they needed. I didn’t realize that’s what that meant.

That moment sparked a larger question: how well do students actually understand the contracts they sign?

Researching contract literacy

Cortes structured her project around contract literacy—an area she found to be underexplored in existing research.

“The first thing was the literature review and seeing what already existed,” she said. “We found very minimal research. A lot of it pertained to financial literacy.”

From there, she designed and distributed a survey to CMU students.

“We spent time constructing the survey, hand-picking questions,” Cortes said. “We wanted to use the data from every question.”

The results supported her initial hypothesis.

“Students are not understanding the things they’re signing,” she said. “There’s a large lack of contract literacy. Although the College of Business had a slightly heightened understanding.”

Beyond research: Creating a real resource

The capstone didn’t stop at data analysis. As part of her project, Cortes created a tangible resource for students.

“She actually came up with this beautifully designed brochure,” Lauderman said. “It gives students some information and confidence on how to approach a contract, what the common pitfalls are, and what the red flags are.”

The brochure is currently available in the finance and law department office, with plans to share it more broadly.

Growth through collaboration

For both student and advisor, the process became deeply collaborative.

“We developed a friendship throughout this whole process,” Lauderman said. “We really were peers, working together toward a common goal.”

Lauderman intentionally stepped back to let Cortes lead.

“I wanted to take a back seat and let her guide where this project was going,” she said. “She did a really good job taking the lead and asking when she needed help.”

Cortes said the experience required initiative across campus, from working with the library’s law researchers to navigating IRB approval and printing services.

“I had no idea where some of these offices even were,” she said. “It was definitely a learning experience.”

Advice for future honors students

As graduation approaches, Cortes reflects on the capstone with pride—and reassurance for others who may feel intimidated.

“I know it can be so daunting,” she said. “The capstone kind of looms in the background when you first start. It sounds cheesy, but it really kind of comes to you. You’re going to be able to figure it out.”

Lauderman agrees and says she would gladly serve as an advisor again.

“It would be easier the second time around,” she said. “You’re already over the learning curve.”

Together, their experience reflects what the honors capstone is designed to do: push students beyond coursework, foster meaningful mentorship, and transform curiosity into applied, real-world insight.

Strong partnerships, they found, make challenging work not only possible—but deeply rewarding.