From fossilized past to sustainable future: Finding the right rock cap

Researcher explores for the right place to store carbon gas

The story of Natalia Zakharova’s latest research project starts 500 million years ago when Michigan was at the bottom of a shallow sea.

Dust, dirt and decomposing organisms floated down through the water to the bottom, forming layers. Layers slowly formed on top of layers, with new sediment compressing the old into two kinds of rock.

One, created by very fine particles, formed rock like shale, smooth on the surface but the particles so tightly compacted that there is little room for water or gas to move through it.

The other, created by bigger particles, formed rock-like sandstone with tiny – sometimes microscopic – pores through which fluids and gases could seep.

Zakharova’s work focuses on identifying the first kind to help unlock the storage potential of the second. She is working with researchers at other institutions to figure out how to store carbon dioxide underground.

To do it, they need to find formations with the more porous rock on the bottom to store the gas and the denser on top to prevent it from escaping back into the atmosphere, said Zakharova, a member of the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences faculty.

Carbon dioxide is very light, she said. Squirt it into the ground and it will try to work its way back to the surface and escape.

The dense rock provides a cap, but the gas will also work its way horizontally looking for a way up. So, they need to find a cap that covers a large enough area.

They also need to identify caps strong enough that the pressure of the trapped gas doesn’t rupture the cap.

“If the containment is compromised, the carbon dioxide can flow through,” she said.

While they understand the basic construction of rock, it’s also not formed with uniform density and strength. In one place, it might withstand the pent-up pressure of stored carbon. A short distance away, it might have a brittle streak that pressure would cause it to break.

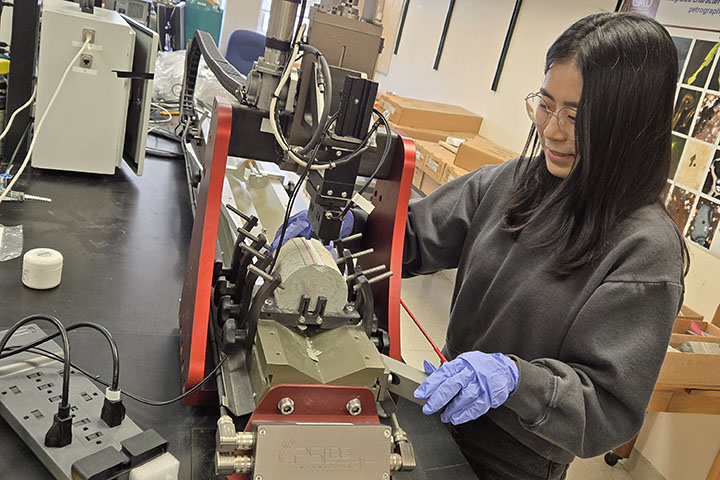

Examining core samples to locate caps sufficiently strong to keep the carbon dioxide below ground has provided opportunities for undergraduate students working in her lab, Zakharova said.

One just presented at a Geological Society of America conference, she said. Two more will work with her this summer.

The grant that is funding the multi-institutional project lasts for two years, she said. Analyzing the data will provide research opportunities for years after it ends.