Newspapers in Michigan

If,

as it has been said, that journalism is the first draft of history,

then newspapers are the original history books. Because of the close

relationship between reporters and scholars, it is particularly

appropriate that the Clarke Library celebrate

the 200th anniversary of Michigan’s first newspaper’s publication.

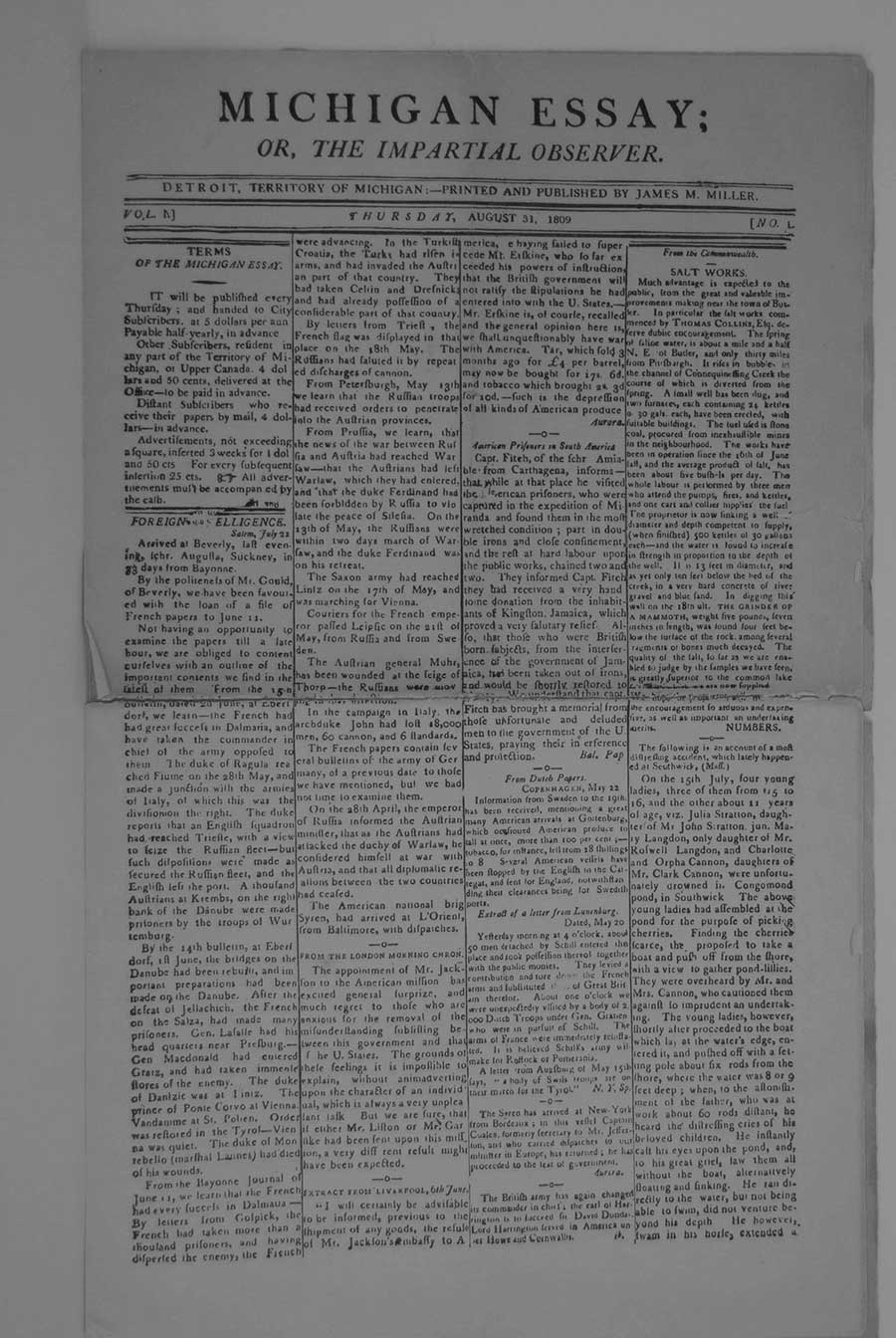

On August 31, 1809 the Michigan Essay: or the Impartial Observer,

appeared on the streets of Detroit. It was a small paper of only four

pages, one of which was

printed in French, and, in the end, a very short-lived enterprise.

But those few pages opened one of the most important windows on Michigan

and its people. Americans, then and now, learned about their world,

exercised their democratic rights, discovered

what was happening in their community, and planned their weekly

shopping trips all from the same source at the same time. And when the

rush of daily life past by yesterday's paper, it was taken up by

historians, who continued to use it for their own

purposes.

If,

as it has been said, that journalism is the first draft of history,

then newspapers are the original history books. Because of the close

relationship between reporters and scholars, it is particularly

appropriate that the Clarke Library celebrate

the 200th anniversary of Michigan’s first newspaper’s publication.

On August 31, 1809 the Michigan Essay: or the Impartial Observer,

appeared on the streets of Detroit. It was a small paper of only four

pages, one of which was

printed in French, and, in the end, a very short-lived enterprise.

But those few pages opened one of the most important windows on Michigan

and its people. Americans, then and now, learned about their world,

exercised their democratic rights, discovered

what was happening in their community, and planned their weekly

shopping trips all from the same source at the same time. And when the

rush of daily life past by yesterday's paper, it was taken up by

historians, who continued to use it for their own

purposes.

As part of this celebration the Clarke Library has published a history of our state’s newspapers. We hope those who read this history will find it as informative, lively, and interesting as the best in local journalism.

Michigan's First Newspapers

In 1835, that most perceptive observer of American society, Alexis de Tocqueville,[1] wrote

that Americans settled the wilderness with three things: their axe,

their Bible and their newspaper. De Tocqueville’s view of newspapers on

the frontier were hardly unique. Sandor Farkas, a Hungarian traveler who

published his views about the United States in 1831 noted that: “the

magic at work in America is the printing of newspapers. … No matter how

remote from civilization or poor the settler may be, he reads the

newspaper.”[2] In

1836 Harriett Martineau, A British traveler who visited the United

States and whose published account of her journey was generally critical

of America, wrote specifically of Michigan newspapers:

In 1835, that most perceptive observer of American society, Alexis de Tocqueville,[1] wrote

that Americans settled the wilderness with three things: their axe,

their Bible and their newspaper. De Tocqueville’s view of newspapers on

the frontier were hardly unique. Sandor Farkas, a Hungarian traveler who

published his views about the United States in 1831 noted that: “the

magic at work in America is the printing of newspapers. … No matter how

remote from civilization or poor the settler may be, he reads the

newspaper.”[2] In

1836 Harriett Martineau, A British traveler who visited the United

States and whose published account of her journey was generally critical

of America, wrote specifically of Michigan newspapers:

At Ypsilanti, I picked up an Ann Arbor newspaper. It was badly printed; but its content were pretty good; and it could happen nowhere out of America, that so raw a settlement as Ann Arbor, where there is difficulty in procuring decent accommodations, should have a newspaper.[3]

It is clear that nineteenth century America could do without many things, but one of them was not a newspaper.

To meet this need, Michigan’s first newspaper, The Michigan Essay: or the Impartial Observer, appeared on the streets of Detroit on August 31, 1809. A short-lived publication, like most western publications prior to the Civil war, was a small, handset, “scrubby” publication.[4] It would be many years before Michigan’s second newspaper was printed. In 1817 the Detroit Gazette appeared. Unlike the Essay the Gazette would have a much longer life, although like its predecessor it was partly printed in French.[5]

As the list below indicates, Michigan’s earliest newspapers followed Michigan’s first settlers. Thus, most of the state’s first papers appeared in the lower peninsula’s southern tier of counties. Prior to Michigan’s admission into the Union in 1837 newspapers were established in the following communities:

- Detroit (1809)

- Monroe (1825)

- Ann Arbor (1829)

- Pontiac (1830)

- White Pigeon (1833)

- Adrian(1834)

- Tecumseh (1834)

- St. Clair (1834)

- Kalamazoo (1835)

- Niles (1835)

- Mount Clemens (1835)

- Centreville (St. Joseph County, 1836)

- Constantine (1836)

- St. Joseph (1836)

- Marshall (1836)[6]

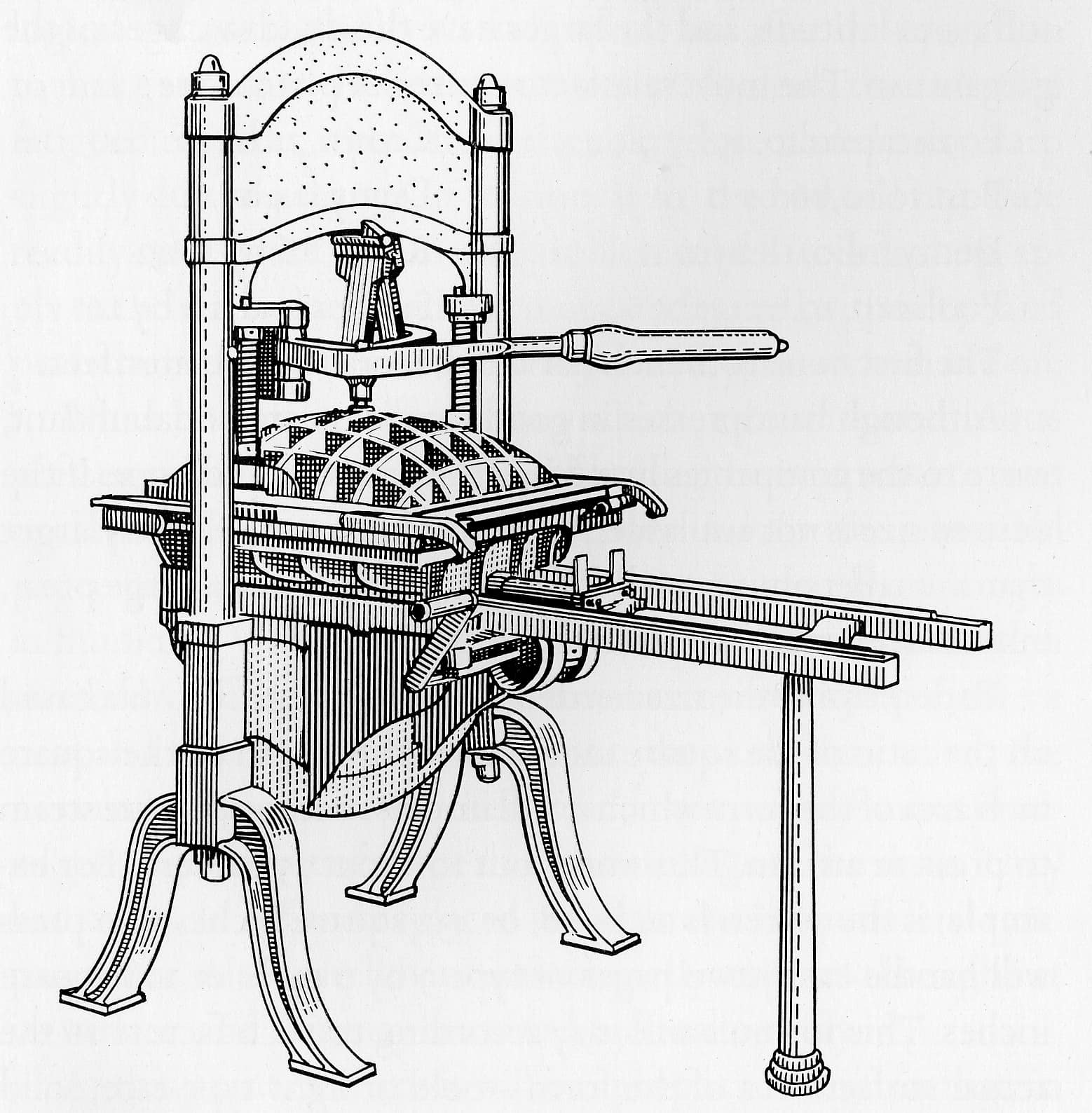

In 1840 Michigan boasted thirty-two newspapers. By 1850 the number had grown to fifty-eight.[7] Most of these were “shoestring” operations. A young printer with little capital but considerable determination could usually purchase an old hand press for a low price and often with little cash and a promise to pay the balance later.

Role in Pioneer Communities

Newspapers before the Civil war, and in large measure throughout the nineteenth century, played three principle roles. Pioneer papers tended to be a mixture of boosterism about the community and a tool to advocate for a political party. As the century progressed, newspapers became more and more a vehicle for news, both national and local, as well as a tool through which advertisers could inform and persuade the community about the quality of their products and services.

Pioneer

papers, however, had surprisingly little local news. Communities were

often small and it was easy enough to hear gossip of the neighbor’s

doings. More to the point, in pioneer communities were settlers often

sought a new start from what sometimes was an unhappy personal history,

it was sometimes wiser not to inquire too closely into neighbor’s past.

Instead, pioneer newspapers preached the virtues of the town and a

political party.[8]

Pioneer

papers, however, had surprisingly little local news. Communities were

often small and it was easy enough to hear gossip of the neighbor’s

doings. More to the point, in pioneer communities were settlers often

sought a new start from what sometimes was an unhappy personal history,

it was sometimes wiser not to inquire too closely into neighbor’s past.

Instead, pioneer newspapers preached the virtues of the town and a

political party.[8]

In the years before the Civil War, Michigan’s newspapers, like most throughout the United States, were intensely political. They often filled their pages with speeches made by favored politicians or political essays penned by the editor. This partisanship, far from being considered an evil, was instead worn as a badge of honor and integrity.[9] Newspapers proudly proclaimed the political principles that guided their publications. Editors distrusted newspapers which claimed to be “independent” on the theory that such a paper almost certainly had an agenda but it was being concealed, likely for some nefarious reason. Reflecting this trend, the 1850 census listed only 5% of the nation’s newspapers as “neutral” or “independent.”[10]

Editors not only supported candidates in their paper, during election years, particularly during presidential elections, they often printed separate campaign newspapers that lasted only for the length of the campaign. For example in 1840 the Michigan State Journal (Ann Arbor) also published the Old Hero, in support of Harrison and Tyler. Elsewhere in Ann Arbor the Democratic Herald briefly revived the Michigan Times in support of Martin Van Buren. [11]

Principle, however, was linked to the subsidies paid to editors by politicians. This practice, which in one way or another remained fairly common late into the nineteenth century, was not viewed as “buying influence” but rather as a way to ensure the political voice of a particular party or party faction was heard. Editors were not bought by an explicit or implicit bribe but rather hired with the clear understanding that they would support the party or faction which made possible the paper’s publication. It was simply part of the job.

In this environment the role of the editor was that of partisan representative. In the hands of a lesser man, this could often simply mean serving as a party hack as well as a refusal to acknowledge unpleasant realities. For example, in 1832 the Detroit Free Press, faced with reporting the unpleasant fact that the Democratic candidate for Congress had been defeated by an overwhelming majority, delayed printing the news for three weeks. Eventually, when forced to concede that the opposition had won, the Free Press put the best possible partisan spin on the news, saying:

The Democratic Republicans can draw abundant consolation from the circumstances attending the campaign; from the certainty that they have effected an organization, and that they will hereafter be prepared at all times to met the enemy and beat them.[12]

Michigan newspapers also promoted Michigan settlement generally and extolled the virtue of their community. Land speculators, often created a newspaper for the purpose encouraging investment or settlement. The Oakland Chronicle was founded in Pontiac in 1830 to “boom” the area. The first newspaper in Saginaw, was published in 1836 at the behest of a group of investors who had purchased “the city of Saginaw.”[13] Similarly, one of the early products of the Detroit Gazette was a poem entitled “The Emigrant,” which looked suspiciously like a speculator’s promotion in that the author shared with readers, “informative notes” and “facts” such as that hay in Michigan grows in vast quantity with almost no effort and that Michigan bees produce an unusual quality of honey.[14] Boom papers could be short lived. After a lifespan of only a year the Oakland Chronicle had served its purposes in promoting settlement and the owners sought to dispose of the press. It was sold to a group of Democrats, seeking to establish a party organ in Detroit, and who subsequently used the press to found the Detroit Free Press.[15]

The Upper Peninsula’s first paper, the Lake Superior News and Miners’ Journal, established in July 1846, had a similar theme. In an editorial published in its first issue, the editor spoke of the region’s mineral wealth, and established as the paper’s goal:

To foster its developments – to point out its advantages – to represent the interests of those who may invest their capital and energies within our district, and give to the public broad correct and faithful medium of mining intelligence.[16]

The editor went on to write that paper the paper’s news would be of a character “studiously eschewing everything of a political character.” [17]

Government and other legal printing was also an important source of income, and in some cases seems to have been the sole reason for a newspaper. The North Star, also printed in Saginaw, made money by printing lists of “paps,” land that had been repossessed by the government and was available for resale.[18] Like the North Star, Flint’s Wolverine Citizen also was published primarily to advertise tax and mortgage sales.[19] Similarly, Ingham County’s first paper, the Ingham Telegraph, appeared in 1842 primarily to print tax lists. In contrast, Lansing’s first paper, the Expounder, was unique in that it was founded in 1849 by an evangelist for the Universalist church, who created the paper to discuss culture and religion.[20]

Part of the financial formula employed by most papers included advertising. Early on editors found it possible to put aside their personal or editorial positions in order to run an ad. For example the Western Emigrant, Ann Arbor’s first newspaper, at one point strongly supported temperance. This view, however, did not restrain the editors from accepting an ad touting the discovery of a new distilling process, available for sale in both Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti. The editors, apparently slightly embarrassed by the inconsistency of accepting the advertising, claimed in an editorial that the still produced a “valuable oil” in addition to “liquid poison,” that is whiskey.[21] Many years later the Detroit Free Press, rabid in its support of Democratic politics and violently opposed to the abolition of slavery, nevertheless printed six paid advertisements for “Foster’s Panorama of Uncle Tom’s Cabin” when the show appeared in Detroit for six nights. The Free Press, like the Western Emigrant, saw no need to turn down a profitable ad even if it represented a gross inconsistency with the paper’s editorial policy.[22]

The willingness of early newspapers to accept ads from any source was likely based, in part, on the scarcity of paid ads. In 1839 both the Herald of Ann Arbor and the Pontiac Jacksonian lamented the fact that merchants failed to realize the importance of advertising in obtaining sales. When, in late 1839, the Herald printed an advertisement, the editor wrote, “Lo! The columns of the Herald, for the first time except one, exhibit a merchant’s advertisement![23]

Most newspaper editors also supplemented their income by printing items other than the newspaper. Indeed newspapers were often a way an established printer obtained additional income. Michigan’s first paper, for example, was printed James Miller, whose principle client was Detroit priest, Father Gabriel Richard. In 1808 Richard had arranged for a press to be brought to Detroit, and he subsequently convinced Miller to come to the city primarily to print various small books Richard desired to be available in the community. The first imprint to come from the press was a twelve-page spelling book for school children. Miller, however, like many itinerant printers, moved frequently in search of better employment. By late 1810 he had left Detroit for New York State. Similarly, the printers of the Detroit Gazette quickly used their political influence to become “printers to the territory,” thus becoming the first state printers. This pattern of supplementing income by doing job printing continues to this day in many newspaper offices.[24]

Pioneer Journalists

Prior to the Civil War most newspaper editors were trained as printers. A newspaper was, for them, often simply a way to keep the press busy between printing jobs. With no journalistic training, these editors published whatever was at hand, including items taken from other newspapers and partisan political material. Some looked back at this training sentimentally. John W. Fitzgerald would reminisce in the early years of the twentieth century regarding how:

It was customary in those early days for the country weekly to reprint the speeches of senators and congressmen, if such officials had made themselves known to the country and their speeches had become of general interest. Here again was work of an educational character for the young typesetter; he became so absorbed in the work of putting the speeches into type that he had some of them committed to heart. He learned style, grace and eloquence of expression, and above and over all he was acquiring a knowledge of the great questions and issues that were attracting public attention.[25]

Using a phrase common at the time, Fitzgerald referred to serving as a printer’s apprentice as “The Poor Boy’s College.”[26]

Working in “the college” was a long, hard job. S. B. McCracken, writing in 1891, recalled his apprenticeship, which began in 1837 when he was thirteen years old:

The printer’s apprentice usually boarded with his master and slept in a bunk in the office. He was required to do the office chores, to cut and carry up the wood for the use of the office, and to carry the papers in town, and in many cases he was required to cut the wood and do other chores at the house also. If in addition to this he did what was expected of him in the way of legitimate office work, he underwent a discipline not without its results in the formation of character. The mental discipline necessarily connected with his calling, and the opportunities for reading, if improved, were supposed to fit him for the editor’s chair.[27]

McCracken went on to describe what the job was to sit in that chair:

The editor was therefore, the embodiment of every requirement from the editor down and the devil up. He was type setter, job printer, foreman, business manager and pressman, as well as editor, and did not shrink for the duties of roller boy upon occasion.[28]

Editors, in addition to doing everything needed to print the paper, were often a quarrelsome lot who found themselves in conflict with each other and with the individuals mentioned in their newspaper. As Fitzgerald notes:

It is true that is some sections and in some towns and even cities those days, party lines were so closely drawn that the press was given to narrowness. Editors were in the habit of calling one another hard names; were a paragraph or two of some of the epithets hurled at one another given here as used to appear in a political discussion between Newspapers of opposite beliefs in those days, the public would conclude that all the virtue we, so often these days claim does not exist, was out of date half a century ago.[29]

A long time Ann Arbor editor put the matter more succinctly, referring to the habit of editors to engage in public quarrels as “the leprosy of the press.”[30]

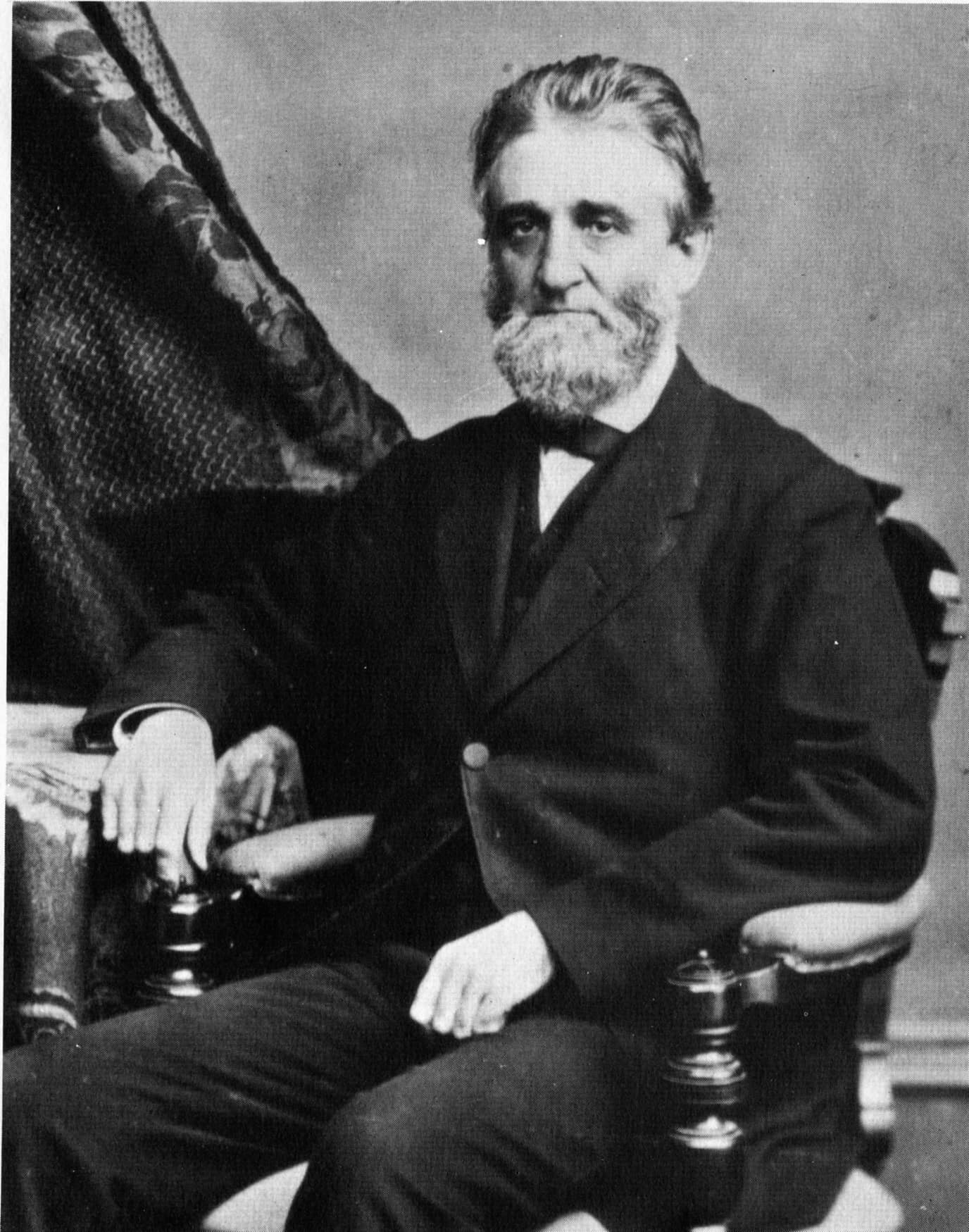

Of

those who hurled such invective, among the most well documented is the

previously mentioned Wilbur Storey. On February 2, 1853 Storey, who at

age 12 had been educated through the Poor Boy’s College by serving as an

apprentice at the Middlebury, Vermont Free Press, became editor of

the Detroit Free Press. Storey had no trouble articulating his or his

paper’s politics: “The Free Press will be radically and thoroughly

democratic.” He went on to add “and not in name merely, but in the

advocacy of those principles of popular liberty which have always been

the cardinal doctrines of the republican (state’s rights) party in this

country, and which are supporting pillars of the Union.”[31]

Of

those who hurled such invective, among the most well documented is the

previously mentioned Wilbur Storey. On February 2, 1853 Storey, who at

age 12 had been educated through the Poor Boy’s College by serving as an

apprentice at the Middlebury, Vermont Free Press, became editor of

the Detroit Free Press. Storey had no trouble articulating his or his

paper’s politics: “The Free Press will be radically and thoroughly

democratic.” He went on to add “and not in name merely, but in the

advocacy of those principles of popular liberty which have always been

the cardinal doctrines of the republican (state’s rights) party in this

country, and which are supporting pillars of the Union.”[31]

What led some to read his paper, in addition to his inclusion of local news and frequent ventures into sensationalism, was that Storey was alleged to be able to say meaner things in fewer words than any other editor. Although in his first published editorial he claimed that it was his desire to “cultivate relations of the utmost courtesy,” within weeks of his arrival he was embroiled in what was to become a never-ending series of lawsuits. This one was caused when he alleged a rival editor had been imprisoned in the New York State penitentiary. When Storey received news of the lawsuit he responded in his paper by writing, “we have yet to learn that it is possible to libel a wretch who is the living personification of falsehood . A living, moving gangrene in the eyes of the community – a stench to the nostrils of decency.”[32]

Storey’s pension for a sharp tongue, a sharper pen, and rabidly partisan opinion, eventually led him to write and publish what has become for some historians the benchmark of newspaper opposition to the Lincoln administration in the day leading up to the Civil War. “Fire in the Rear” criticized Republicans who sought to take the nation to war. Speaking of the likelihood of war between North and South, Storey wrote:

…if the troops shall be raised in the North to march against the South, a fire in the rear will be opened upon such troops which will either stop their march altogether or wonderfully accelerate it . . . We warn it [the Lincoln administration] that the conflict which is precipitating will not be with the South, but with the tens of thousands of people in the North. When civil war shall come, it will be a war here in Michigan and here in Detroit, and in every Northern state.[33]

When war finally came, Storey wrote, under the heading “They Will Not Forget,” that

Democrats and all conservative men will do their duty in the present dreadful emergency, but they will not for a moment forget though the war be of 10 years’ duration, that it was the result of course which they had steadfastly, persistently and untiringly protested. … Let nobody suppose that while as journalists and citizens we support the government … we shall cease to hold up to the scorn and detestation of mankind those party leaders who have purposely and maliciously conspired for the shedding of blood. Nor and those party leader turn the public eye from their crimes by boisterous exhibitions of spurious now or hereafter.[34]

In June 1861Storey left Detroit to become editor of a Chicago newspaper.[35]

Storey

was so extreme that even his fellow Democrats often had trouble with

his attitudes. Of his “fire in the rear” editorial, the more moderate

but equally Democratic Kalamazoo Gazette editorially lamented Storey’s

“immoderate language.” Printed in Ann Arbor, the Democratic Michigan

Argus also repudiated the

editorial.[36] Democrats

became particularly incensed because Storey’s extreme opinions were

often used by opposition newspapers as representing the views of the

Democratic party. In frustration, the Hillsdale Democratic Gazette

wrote, “[the Detroit Free Press] is well-known to speak only the views

of W. F. Storey and Co., (a very small company at that).” The Hillsdale

Democratic Gazette later warned in an editorial, “don’t you know that

Storey can’t be controlled or even advised by anyone – that he is one of

the most self-willed and stubborn men in Michigan? [In addition he] is

almost always wrong.”[37]

If the comments of Democratic papers in Kalamazoo, Ann Arbor, and Hillsdale were critical of Storey, the comments of the Republican papers were even more unkind. Rufus Hosmer, editor of the Republican Detroit Advertiser, and possessing a pen almost as acid as Storey’s, wrote that “Storey is a living illustration of one of the cardinal doctrines of his own church, total depravity.”[38] Hosmer would go on to claim that friends said of Storey:

that he is insufferably egotistical, arrogant, self-sufficient, conceited, overbearing, and dictatorial. That he is without refinement, cultivation, tact, delicacy, good sense or sound judgment. That he is oblivious of his work, wrong-headed to a degree, obtuse and tyrannical. But with these slight qualifications, he is quite considerable of a fellow.[39]

The kind of mudslinging Hosmer and Storey engaged in led other papers to criticize both of them. The Ann Arbor Argus, for example, suggested that both men should be indicted for printing obscene publications.[40] Criticisms of other papers of Storey and Hosmer, however, rarely restrained the same papers from engaging in exactly the same kind of behavior. Exchanges like those between Hosmer and Storey had begun with Michigan’s earliest papers. The state’s first regularly published newspaper, the Detroit Gazette, was described by a historian in the early years of the twentieth century as “caustic.”[41]

When fire destroyed the Democratic Gazette’s press in 1830, it was reported that Whig Judge McDonnel, whose house was also consumed in the same fire, compared the loss of his home to the Gazette’s destruction and said, “there is no evil without a corresponding good.” Another Whig Judge noted about the fire that , “The Gazette people saved their type, I think, for which I am not glad nor anyone else.” Clearly the demise of the “caustic” Gazette was considered by some a benefit to the community.

The caustic tradition of the Gazette lived on in the papers that followed it. T.P. Sheldon, founder of the Detroit Free Press, found himself in the Wayne County Jail for refusal to pay a $100 fine levied by the Michigan Supreme Court which held him in contempt for his comments regarding a court decision. Sheldon’s case became a local political cause and 300 Democrats raised the money to pay the fine through a dinner held in the jail itself. One Whig commentator suggested that never had so many Democrats been found in jail and, for the good of the community, the sheriff should detain them all for ninety days.

As Rufus Hosmer demonstrates, Republicans were as apt to use harsh words as Democrats or Whigs. Hosmer, however, was merely writing in the same vein as many other Republican editors. Joseph Warren, of the Republican Detroit Tribune, was said to be kind and generous, except in politics. Warren was known to wonder how god, in his all wise providence, suffered a single Democrat to live.[42] Unsurprisingly, Warren and Storey soon engaged in vicious editorial attacks on one another that the Grand Rapids Enquirer took both editors to task for editorials “disgusting to the readers and disgraceful to the parties.”[43] The writers of Grand Rapids, however, did not pursue the virtuous path they prescribed for their Detroit colleagues. Arthur White reminisced about the reporters of Grand Rapids, “Writers wrote what they pleased and when news was lacking the editors of one paper roundly abused those of other papers."[44]

Reporters in Grand Rapids could be equally abusive of citizens in their stories. George W. Gage, of the Grand Rapids Times, was remembered for having put to good use boxing classes he took. As a result of his training he “knocked out several prominent citizens who had called for the purpose of beating him to a pulp.”[45] Even when an editor had good intentions, his reception could be rough. A story was told of Chase Osborn, who eventually would be elected a reform governor, that when he was the editor of a newspaper in Sault Ste. Marie a disgruntled reader with a considerable reputation for violence threatened to kill Osborn. In response, Osborn, who himself was very strong, took to wearing an axe on the belt of his trousers, for all to see and with which an attacker would need to reckon.[46]

Newspaper editors who declined to take part in editorial mudslinging were also considered something of a failure in their profession. Discussing early newspapers in the Escanaba area, the Escanaba Daily Press recalled,

In those days of a multiplicity of both daily and weekly newspapers, each paper boasted of its intensely partisan supports and the writer possessed of the most vicious pen, with which he lambasted both issues and characters, was counted as most successful in his field. Passages at arms between rival newspaper editors were an accepted part of h newspaper publishing business in that day and the editor who refused to be drawn into a wordy bale was counted as ‘soft” and soon moved on to a less warlike community.[47]

Although harsh words were common, there is reason to believe on at least some occasions they were largely theater, designed to sell papers. In one particularly memorable instance an ongoing battle between the Detroit Post and Detroit Free Press was resolved by a telephone call. James F. Joy, editor of the Post, called Mr. Quinby, editor of the Free Press. Quinby recalled years later that when Joy suggested the wrangling had become disgraceful, he quickly agreed. “Will you stop it in the Free Press if I will in the Post?” asked Joy. When Quinby said yes the two editors ended their conversation, and their public feud.[48] Despite this example, nineteenth century Michigan newspapers were not for those who disliked reading a harsh word.

Michigan Press Association

In another sign of growing civility, after the Civil War, editors overcame their frequent war of words and in 1867 formed the Michigan Press Association. Although the organization ceased to meet during World War I, it was reorganized in 1922.[49]

The Michigan Publishers Association published an organizational circular in 1868 stating that the purpose of the organization was good fellowship, better acquaintance, and the promotion of the general welfare of the Press.[50] “General welfare” meant many things, but one concern that was repeatedly discussed, well into the twentieth century, was a statewide rate for legal advertising and well as agreement about rates for other forms of ads. A few years later the group explicitly noted that “By the cultivation of friendly relations among ourselves we avoid the jealousies and embittered feelings that are liable to grow out of political differences, and reduce to a minimum the evils of an excited business competition.” [51]

In order to promote membership the MPA in the latter part of the nineteenth century promoted extensive “excursions.” Described as educational opportunities by some, others called them junkets. While members debated whether the tours were educational or recreational, the excursions were clearly popular. In an era when only 25 or 30 members might show up for an annual meeting, 400 individuals participated in the 1885 in an excursion to Traverse City, Charlevoix, and Petoskey. Soon excursions went beyond the boundaries of the state. Excursions became so popular that the MPA discussed purchasing a permanent site for such activity, once seriously discussing purchasing land on Mackinac Island. [52]

Filling the Pages

Although newspapers throughout most of the nineteenth century were candidly partisan, even during election years they needed more than the latest speech by a party official to fill their pages and sell newspapers.

The Niles Republican (a Democratic paper despite the name) offers an excellent example of what a typical pre-Civil War weekly newspaper was like. It consisted of four pages, the first page largely “clipped” material reprinted either from the Detroit papers or from papers printed out-of-state. Much of the front page material would fall into the category of “literature,” often being short, one paragraph anecdotes. . Of the non-news items published the most common theme was humor and the most common format was poetry. Sermons and essays, however, also were given a prominent place in the paper. Page two was usually a mixture of local and national news. Editorials usually showed up in page 1 or page 3, although in an era of intense newspaper partisanship it was often difficult to draw a clear line between an “editorial” and a political “news story.” Page 3 would also have some advertising, but most ads were printed on page four.[53]

The

Niles paper was typical in that much of its material came from

clippings freely reproduced from other newspapers. Where change would

begin to occur was in the place of local news.[54]As

communities became more settled, editors realized that “word of mouth”

was insufficient to keep the community abreast of local events, thus

local news would interest readers. Among the pioneers ingathering and

printing local news was the Detroit Free Press, under the editorial

guidance of Wilbur F. Storey. Storey took a “dull, spiritless montage of

scissors and paste” and infused it with an unending supply of local

news, much of it

sensational.[55]:[56]

“Shocking Depravity”

“How to Get Rid of a Faithless Wife”

“Suicide by Swallowing a Red Hot Poker”

A bit later, when the Free Press began to “stack” headlines, readers were offered leads such as:

HORRIBLE MURDER

A man Shoots at his Wife and

Blows out the Brains of a

Little Daughter and Breaks

His Gun over his Wife’s

Head after the Murder

Storey found news regarding executions was particularly well read. With dubious taste, but a sure instinct for sales, he included as a daily feature a column entitled “Scaffold Scourings.”[57]

Despite his emphasis on local news, Storey lamented that there often simply was not enough local events with which to fill his paper. As he lamented in 1859, “Local news is sadly deficient about these times,” adding “There seems hardly stir enough among the public to keep up appearances of life…”[58] to address this inconvenience, Storey was also willing to print as news articles that were undoubtedly fictional. The Free Press once ran an article entitled, “A Child Eaten by a Bear in Hamtramck” which proved very successful in selling papers, although it did call for the reader to ignore the small problem that the berries the child was allegedly gathering when he had his fatal encounter were not in season and there were no bears known to inhabit Hamtramck.[59] Storey realized, however, like many newspaper reporters before and after him, that sensationalism sold.

Advertising

As the Civil War came to a close, Michigan’s newspapers continued to act out the roles of partisan activists that they had traditionally played. The Detroit Free Press, long the journal of the Democrats, proclaimed just prior to the 1868 in a message entitled “The Opening of the Fall Campaign:”

The Free Press alone in this state is able to combine a Democratic point of view of our state politics and local issues with those of national importance. … [It] will combine political news with a cool and dispassionate discussion of principles and men in such a manner as to afford to the people means of the best judgments as to the truth.[60]

The Free Press was hardly alone in continuing the traditions of antebellum journalism into the era after the War. In 1872, writing under the headline, “For Grant and Wilson,” the Detroit Post proclaimed that it had “no sympathy with the sickly inanity that the Republican Party has accomplished its mission. No party has ceased to be useful while it retained the vitality which initiates all the practical reforms of its age and it is the crowning glory of the organization which as done so much for this country.” Thus the Post stood ready “to meet the demands of the Republicans of Michigan and to advance their cause.”[61]

The nature of newspapers were changing, however, and the Detroit papers exemplified that change. Papers became less partisan, eventually declaring independence from all party affiliation, while at the same time changing the mix of what filled their columns from political essays to “news” stories written in a more gentler tone than that which had filled to pages of previous newspapers. What drove this change is a matter historians continue to debate, some claiming it came about as a result of a new sense of standards among journalists, others the ability to increase profit through the exploitation by advertisers of a non-partisan mass market.[62]

Whatever the cause, the change was clear. In Michigan change was first represented by James E Scripps. As Harper’s Magazine reported in 1888:

One of the most notable features of Western Journalism during the past few years has been the rise and success of the penny and two cents newspapers. The first journalist of the West to discover the demand for journals of this class and to act upon his discovery was Mr. James E. Scripps, the principal owner of the Detroit Evening News. . . . This was the pioneer of the cheap newspaper in the West.[63]

The penny-press had first appeared in New York City many years earlier.[64] As

early as 1849, the Detroit Daily Tribune had both described the penny

press as “the lever that moves the masses” and suggested that “We see no

reason why one or even two, cannot be made permanent in this city.”[65] The Daily

Tribune’s opinion notwithstanding, a penny paper did not appear. It was

Scripps who adapted the formula for the Midwest and brought

the Tribune’s vision to Detroit.[66]

This came about in two phases. The first began in the 1870s when

Scripps made a critical but simple observation: in 1870 only about 30

percent of Detroit English-speaking population regularly read a

newspaper. The principal reason for this was the price of a daily

newspaper. Detroit’s papers sold for a nickel, in an era when a typical

working man made a dollar a day. Because of their price, newspapers were

luxury items. To sell newspapers to the masses required lowering the

price of the paper, but politicians were not inclined to pay the

increased subsidies that this would require and the idea was dismissed

as impractical.

The penny-press had first appeared in New York City many years earlier.[64] As

early as 1849, the Detroit Daily Tribune had both described the penny

press as “the lever that moves the masses” and suggested that “We see no

reason why one or even two, cannot be made permanent in this city.”[65] The Daily

Tribune’s opinion notwithstanding, a penny paper did not appear. It was

Scripps who adapted the formula for the Midwest and brought

the Tribune’s vision to Detroit.[66]

This came about in two phases. The first began in the 1870s when

Scripps made a critical but simple observation: in 1870 only about 30

percent of Detroit English-speaking population regularly read a

newspaper. The principal reason for this was the price of a daily

newspaper. Detroit’s papers sold for a nickel, in an era when a typical

working man made a dollar a day. Because of their price, newspapers were

luxury items. To sell newspapers to the masses required lowering the

price of the paper, but politicians were not inclined to pay the

increased subsidies that this would require and the idea was dismissed

as impractical.

Scripps, however, believed there was a way to make considerable profit by changing the ways newspapers went about paying the bills. In 1873 Scripps pulled together virtually every penny he could find to launch the Detroit Evening News. He priced the paper at two cents. Scripps formula for success was based on strict cost control and expanded sales. Scripps four page paper used smaller pieces of newsprint and thus was physically only about one-sixth the size its competitors. The reduced both paper costs, composition costs, and printing costs. He also avoided fees for telegraphic reports by simply reading and using news published in Detroit’s morning newspapers. Stories, both those borrowed from the pages of his competitors and written exclusively for the News were “condensed,” that is written in the briefest possible form. Scripps applied the same economy of writing to editorials. They were “pungent and forceful,” but rarely exceeded a paragraph in length. Scripps pinched pennies everywhere including bringing in relatives to hold various positions in the paper, and paying them when he had cash, and only as much as he might have on hand.[67]

Scripps pitched his stories squarely at the city’s unserved working class market. His original vision was almost that of a daily educational journal. The writing style, small size, and lack of headlines was not an oversight but rather a representation of Scripps desire to deliver to his audience a small, easily consumed product that would be a source of learning and read from cover-to-cover. As Scripps himself expressed it, he desired “a wide diffusion of wholesome literature.”[68]

Scripps

original plan towards wholesomeness quickly fell afoul of his brother

Edward, who had a keen sense for what the masses would like to read and

whose stories likely made the journal profitable. Edward Scripps

reported on the doings of “rich rascals” and gained for the News a

nationwide reputation for its reporting style. Although the rich rascals

did not particularly appreciate the paper’s invasive reporting, and

responded to it by a barrage of libel suits, some of which were

successful. But Edward remained unphased. He eventually concluded that

the road to profitability was paved by the readership gained through

such reporting. The losses in court were viewed as something akin to a

licensing fee; an inevitable cost of doing business. Although James may

not have envisioned his paper taking this path, he gave way to his

brother’s vision when by 1876 the News had a larger circulation than the

combined circulation of all of the other papers in Detroit. As James

would somewhat coyly concede, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of

the News first publication:

Something really meritorious and

elevating, but in small compass and at a cheap rate, was the ideal I set

myself. But I soon found I had journalistic genius on my staff, and I

was quick to see that true policy, demanded that it have a fair scope.

Had I held everything down to my own views, I should have produced a

good, but dull newspaper.[69]

Scripps second step occurred in the 1880s. The economics of newspaper publications were changing. How the Scripps family adjusted to that change would again reshape the model of newspapers in the state and cause an angry split between James and Edward Scripps. In 1887 James, suffering from an attack of gallstones and fearing he would soon die, decided to tour Europe, leaving Edward in charge. Edward believed that the old-fashioned, four sheet News was doomed. As he wrote at the time,

The cost of paper is racing down hill. I prophesy that very little paper will be sold during 1890, at a higher price than three cents. This means that the competition will require larger papers. . . . I believe that the time is shortly coming when the [Cincinnati] Post will print for a cent an eight-page paper as big as the [two cent] News is now.[70]

Edward’s vision went beyond a larger paper to encompass a different composition. He foresaw much of those additional pages filled with advertisements.

[The News must enlarge] sufficient to monopolize the advertising business that can be gotten, [otherwise] some other papers must take it and over the profits grow rich and hence a powerful competition for the News. … We have been leaving advertising out of the News at a rate of $1,000 a month. That money which advertisers are willing to spend in Detroit or at least a portion of it is going to The Journal, The Free Press, and the Tribune, making them stronger financially and more fashioned for advertisers.[71]

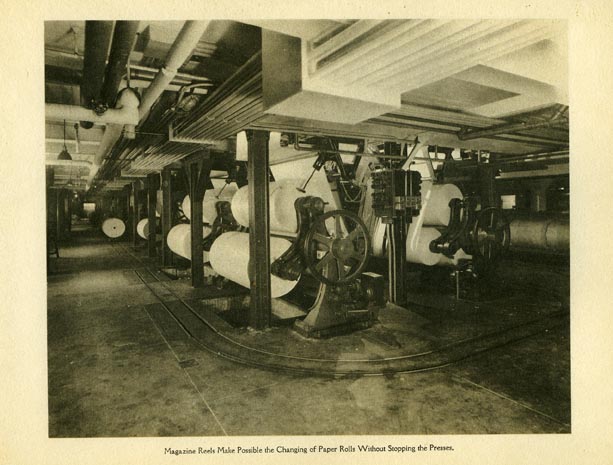

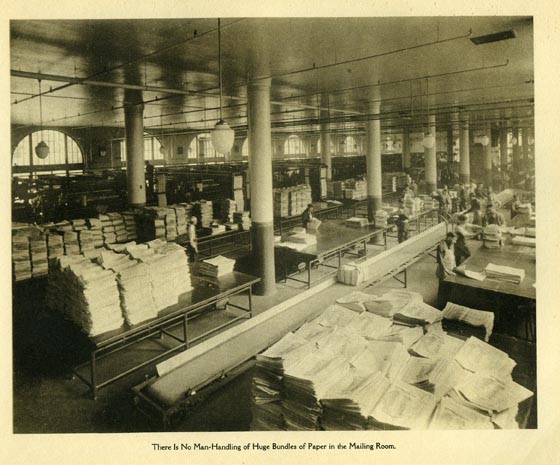

To make his vision possible, Edward committed funds to buy the latest, fastest printing presses then on the market. Unfortunately James, then in England, thought Edward’s analysis wrong and his decision to buy new printing presses an expensive folly. Edward, however, was working with the facts on the ground. Paper prices were falling fast. In 1884 slightly more than 31 percent of the news expenses were for the purchase of newsprint. By 1889 this cost has dropped to slightly less than 20 percent of the budget. In roughly the same time frame Edwards was able to fill this cheaply purchased newsprint with paying ads. In the three years between 1886 and 1889 advertising revenue grew from 38 percent to 58 percent of the paper’s profit. Leading merchants were transforming their advertisements from a few lines of text or a simple business card printed weekly to “display ads’ that changed regularly and consumed large sections of a page. J. L. Hudson and C. Mabley were among the Detroit merchants who pioneered in this trend and whose purchases of advertising space drove the increase in revenue. The appearance of national brands only amplified this trend as distant companies sought to familiarize local purchasers with their product.

George Booth, the son-in-law of James Scripps, later rationalized his father-in-law’s clear misreading of the situation:

It is . . .not unreasonable to suppose that a man like Mr. James E. Scripps of the old school of journalism and in a condition of poor health, felt it quite impossible [to] comfortably to enter upon this new era which meant a permanent discarding of his own ideal of a four-page daily newspaper.[72]

Although Scripps brought the penny press to Michigan, he was not alone in developing material that would appeal to a mass market. The Detroit Free Press developed writers who had wide appeal locally, nationally, and internationally. The writer who was for many years was the star of the Free Press was Charles Bertrand Lewis. Writing under the pen name M. Quad, Lewis in 1870 penned his first humorous column in the Free Press. Lewis had reported for the Free Press in a variety of settings, but like many of his predecessors he found in the ten years he spent covering the police courts the material from which to make his reputation as a humorist.[73]

Although Lewis was well known locally in the 1870s, he became a national figure in the 1880s, eventually being called “the Mark Twain of the middle west.” This accolade came when he began to write an enormously popular column entitled “Brother Gardner and the Lime Kiln Club.” Although he also wrote other humorous columns, for more than a decade this column which followed the activities of the fictitious Lime Kiln Club brought national attention to both the author and his paper. The Lime Kiln Club was written in supposed Black dialect and frequently caricatured the learning and culture of African Americans. Although frequently offensive by today’s standards, in its day it was very successful. Lewis also caricatured other groups, and often used all of his inventions to criticize politicians. For example Lewis has Carl Dunder, his fictional German immigrant, say of American democracy:

I have lived in this country long enough to find out the dot personal liberty means . . . der right to trample on der privileges of somebody else. Der 's constitution guaranties efen der humblest citizen his rights, but I notice dot der more money a citizen has der more rights he gets.[74]

And within the largely racist humor of the Lime Kiln Club Lewis created the character of Brother Gardner, a wise old man well versed in national affairs and who possessed a keen sense of the foibles among Detroit’s white citizens. Occasionally Brother Gardner spoke to a future only dimly perceived:

De time am not fur away when de black men of dis kentry will riz up an’ demand a sheer inde guv’ment an in de spiles…[75]

But the path to this dimly seen future was that of Booker T. Washington. Lewis never embraced racial equality. Eventually the columns were gathered together and reprinted as books. Lewis’s success led to him often receiving offers to write exclusively for other papers. In 1891 Joseph Pulitzer made an offer that lured Lewis away from Detroit to work for the New York World.[76]

With the help of columnists such as M. Quad the Free Press developed into both a national and an international newspaper. The paper created a weekly edition that relied mainly on features for sales. In 1871 circulation of the weekly was 6,100. By 1891 the weekly had reached 120,700, of which only 37,720 were distributed in Michigan. In 1881 the ambitious Free Press staff exploited the popularity of the weekly to establish a weekly edition in London, England. Largely recycling its already printed material, the London edition remained in print until 1899 and at its peak had a weekly circulation of over 200,000[77]

The Campaign of 1896

Politicians did not readily give up control over vehicles of publicity. Indeed, ownership of a newspaper was deemed essential in intra-party struggles. In the mid-1860s, the Detroit Advertiser and Post, long the state’s leading Republican newspaper, began to stray from the path charted by Zachariah Chandler, the state’s leading Republican. When the paper added to this shortcoming the failure to endorse the complete slate of candidates, Chandler and a few of his friends founded the Detroit Post. The Post was intended, according to one's source, to “offset the lukewarm if not hostile influence of the Tribune and at the same time [to] properly chastize it.”[78] However when Chandler finally lost his senate seat in 1875 the reason for the two papers ended and in 1877 the two papers merged and was renamed the Post and Tribune. Ownership of the merged paper remained in the hands of Republican politicians until it was sold to James Scripps in 1891. A decade earlier, in 1883,new factionalism among Republicans led to the founding of the Detroit Journal. The Journal struggled financially, but in both 1886 and 1892 Republican Senator Thomas Palmer invested substantial sums of money to keep the paper afloat and his political views prominently displayed.[79]

The

presidential campaign of 1896 proved the final undoing of the partisan

press. In 1893 Depression gripped the country and as the presidential

campaign of 1896 began the nation was gripped by a vigorous debate over

the nature of currency. Those who believed the depression could be ended

by inflation urged that the United States treasury abandon the “gold

standard” and allow easier to obtain silver to support the currency. The

battle was bitter and with many consequences. Among the consequences

was the final separation of most major newspapers from party

affiliation. For example, the Detroit Free Press, long the Democratic

Party’s faithful party organ, broke with the party, and declared its

independence. This act came as no surprise. The paper had been at war

with Detroit’s Democratic mayor Hazen Pingree since 1895, who repaid the

bad press he received at the paper’s hands by claiming that he

“wouldn’t believe the weather reports” printed in the paper.[80] It

was not such a large step to move from criticizing Detroit’s Democratic

mayor to abandoning the party’s presidential nominee.

Nor was the Free Press alone in defecting from the Democratic fold. Joseph L. Titus, a life-long Democrat and editor of the Livingston Democrat, published under his supervision in Howell since 1857, also bolted. Of the ticket, Titus believed that, “They were not Jeffersonian, they were not Jacksonian, they were not Democratic, and he would have none of them.”[81]

It seemed as if the 1896 presidential campaign took the last wind out of overtly partisan sails. By 1900 newspapers across the state and across the country no longer served as partisan organs. Whereas in the past parties simply established new papers to present their views, the heavy investment necessary to create a widely distributed newspaper no longer made this possible. Economics had forced political parties out of the newspaper business.[82]

The end of overt partisanship, however, did not mean that twentieth century newspapers abandoned consistent political views or strong party preferences. The historically Democratic Detroit Free Press, once it broke with the Democratic Party in 1896, consistently supported Republicans for the presidency until the paper endorsed Jimmy Carter in 1976.[83] In a second example, a study of six Michigan newspapers coverage of the state’s 1960 congressional campaigns, found that while all six papers were generally non-partisan in their news coverage of the campaigns, only one of the six papers studied, the Traverse City Record Eagle, was non-partisan on its editorial page. The other five papers displayed a preference toward Republican candidates.[84]

Newspapers also adopted other crusades, For example the long-time editor of the Escanaba Journal, was remembered as a

… violent Prohibitionist and in the prolonged “Wet” and “Dry” battle in this county he led the prohibition forces through many a knock down an drag out campaign. After prohibition became a reality he became actively engaged in protecting the prohibition regime…[85]

Papers continued to have strong editorial views, but those views were more often disconnected from the news columns.

The New Journalists

As the nineteenth century slowly gave way to the twentieth century, the education and background of the people writing in newspapers began to change. Unlike the largely self-educated and highly entrepreneurial editors of Michigan’s pre-Civil War era, the new journalists often were well educated and worked for a salary, rather than created their own newspaper. Much of this change came about for the same reason that political parties could no longer afford to support their own newspaper. Whereas founding a newspaper before the Civil War generally involved a relatively small investment that an enterprising young man trained in printing could reasonably hope to find, after the Civil War this was increasingly less possible, particularly in the larger cities. Similarly as large city papers grew, they tended to develop larger, more specialized positions. Few reporters could be depended on to run a press, and fewer pressmen possessed the skills to write a story. Increasingly the amount of specialized knowledge needed to run specific aspects of a newspaper was such that it was impossible to be the jack-of-all trades that the pre-Civil War editor usually was.

These new reporters also brought a new sensibility to their job. They were generally schooled in the belief that reporters should approach their work, particularly anything involving politics, with neutrality. They should report the facts and let the public, or at least the editorial page writers, draw the conclusions. As one pioneering journalism textbook had it, the reporter’s job was to gather, “facts, facts, and more facts.”[86]Facts, however, were not necessarily of a high minded variety. Sensationalism had long been used to sell newspapers and editors and reporters became ever more colorful in their seeking after the next big story. Indeed the lengths to which newspapers would go for a story disturbed many. At the close of the nineteenth century one of the pathbreaking works establishing a “right of privacy” was written directly in response to the excesses of the press.[87]

Michigan's Metropolitan Papers

At the beginning of the twentieth century advertisements made up two-thirds of the revenues received by many newspapers. Indeed one wag had it that subscriptions only paid for the blank newsprint. Everything else – the reporters, the printing press, production, delivery, and of course the profit, was paid for by the advertisers.[88]

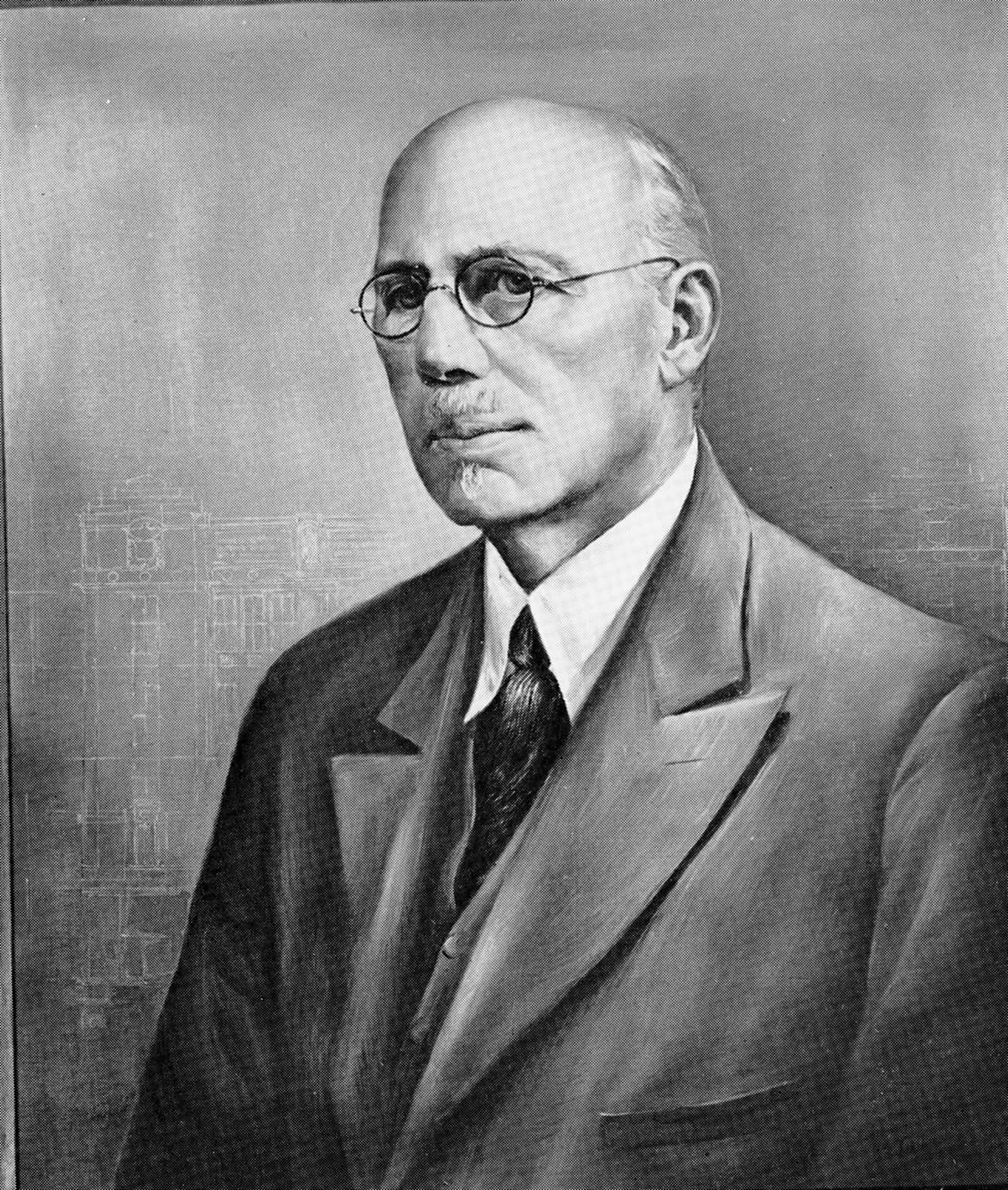

Although

Detroit was the center for these papers, the model was copied by daily

papers in many other Michigan cities. Indeed, among the most in

implementing the model was George Booth. The son-in-law of James Scripps

and Scripps successor at the Detroit News, Booth saw an

opportunity to use the formula in many other Michigan cities. In 1893

Booth purchased the weakest paper in Grand Rapids, the Morning Press. Shortly afterward he purchased the also ailing Grand Rapids Evening Leader. In November 1893 he combined the two papers into the newly issued Grand Rapids Press, which, using the formula developed at the News, was profitable within six months and quickly became extremely successful.[89]

Although

Detroit was the center for these papers, the model was copied by daily

papers in many other Michigan cities. Indeed, among the most in

implementing the model was George Booth. The son-in-law of James Scripps

and Scripps successor at the Detroit News, Booth saw an

opportunity to use the formula in many other Michigan cities. In 1893

Booth purchased the weakest paper in Grand Rapids, the Morning Press. Shortly afterward he purchased the also ailing Grand Rapids Evening Leader. In November 1893 he combined the two papers into the newly issued Grand Rapids Press, which, using the formula developed at the News, was profitable within six months and quickly became extremely successful.[89]

Booth, along with his two brothers Edmund and Ralph, did not immediately capitalize on George’s success in Grand Rapids. However they eventually began to build a small, profitable chain of newspapers in Michigan’s industrial heartland. In 1907 the Booth’s purchased the Muskegon Chronicle. In 1910 the brothers added the Saginaw News to their chain, and in 1911 the Flint Evening Journal. In 1918 the brothers, now incorporated at the Booth Publishing Company, combined two papers in Jackson to create the Jackson Citizen-Patriot. The Ann Arbor News and the Kalamazoo Gazette were also soon added to the chain.[90]

Booth’s formula for success was, in principle, quite simple. The paper should be outstanding in its operations and , whenever possible, be the only newspaper in the community. Booth would eventually explain,

Elimination of competition puts an end to the miserable wrangling that once characterized so many newspapers. It assures a community a steadiness of purpose on the part of the publisher; poise in the presentation of news and opinion; greater efficiency in operation; reduction of expenses; more complete service to the advertiser at a lowered unit cost. It tends also to reduce contention in the community. On the other hand, the paper which is fortunate enough to occupy a filed alone, where once it had competition, must beware of smugness; of being too well satisfied, of employing its strength unjustly; of becoming greedy; of being biased or partisan. There are times when the most independent paper must take a firm stand, but it should be on a well-reasoned basis.[91]

New Economic Realities

Although the nineteenth century saw the rise of the great metropolitan daily newspapers and the first years of the twentieth century saw the model applied successfully too many Michigan cities, forces were already at work that would lead to the decline of many newspapers. As George Booth had seen, consolidation recognized that advertisers seeking a mass audience supported most generously the paper with the largest circulation. His views were undoubtedly informed by his father-in-law, James Scripps, who in 1879 expressed the rationale for consolidation:

I believe there are too many newspapers, not alone for the good of their publishers, but for that of the community. With two rival grocery stores the public gets its tea and its sugar at cheaper rates. It is not so with its newspapers . . . The expense of printing two newspapers . . . is double what it costs of a single paper would be . . . With the diminished patronage both papers must be smaller, advertisers, of course, must receive correspondingly less benefit . . . the remedy for supernumerary papers is consolidation.[92]

In 1909 the number of daily newspapers printed in the United States peaked at 2,609. By the 1920s the ritual of reading the daily paper was firmly entrenched in American society. Despite the competition of radio that ritual remained largely unchanged into the 1950s. However, the concluding half of the twentieth century saw newspaper circulation experience a steady, long-term downward trend.[93]

The newspapers printed in Detroit exemplify this pattern. In 1899 the last daily newspaper founded in the city, the Detroit Times, began publication. With its appearance, Detroit boasted five dailies. In 1915 the News, which since 18xx had owned and published the Morning Tribune, closed that paper. Four years later the News purchased and closed the Journal. The three remaining papers shouldered on, with the weakest, the Times, receiving a major infusion of cash and talent when it was bought by the Hearst chain in 1922. The 1950s, however, were financially difficult years for all of Detroit’s papers. Competition for advertising revenue from radio and television, coupled with several lengthy and bitter strikes, were taking a toll. In November 1960 the News , which had saw its circulation lead over the Free Press slowly slip away, bought and closed the financially troubled Times. The move came about largely to preserve the News status as the paper with the largest circulation in the city, and the associated advertising revenue that came with that position.[94]

The

consolidation of Detroit’s papers into two dailies led to a period of

journalistic excellence spirited rivalry, and expanding costs. The war

between the News and the Free Press was proving an

expensive one that the owners of both papers could neither end nor win.

In 1985, after suffering more than $20 million in losses, the

independent paper James Scripps had founded more than a century earlier

was sold by his heirs to the Gannett Company. At the time of the sale,

Gannett’s chairman, Al Neuharth, addressed the employees of his latest

acquisition. Neuharth’s acquisition of the News had more than a little irony in that during the 1960s he had worked “down the street” at the Free Press.

Neuharth’s comments that day seemed to say that the long war between

the two papers would go on, and he assured his new employees that in the

end the News would triumph.

The

consolidation of Detroit’s papers into two dailies led to a period of

journalistic excellence spirited rivalry, and expanding costs. The war

between the News and the Free Press was proving an

expensive one that the owners of both papers could neither end nor win.

In 1985, after suffering more than $20 million in losses, the

independent paper James Scripps had founded more than a century earlier

was sold by his heirs to the Gannett Company. At the time of the sale,

Gannett’s chairman, Al Neuharth, addressed the employees of his latest

acquisition. Neuharth’s acquisition of the News had more than a little irony in that during the 1960s he had worked “down the street” at the Free Press.

Neuharth’s comments that day seemed to say that the long war between

the two papers would go on, and he assured his new employees that in the

end the News would triumph.

The thing that really pleases us is the way the position of the Detroit News has been solidified as number one in this very, very attractive Michigan market. And you know that the fact is, the News is number one in every respect, no matter how you measure it. You’re number one in news content. You’re number one in public service. You’re number one in circulation. You’re number one in advertising. Now, I can tell you of the importance of that, having worked down the street at number two for several years. So that number one position is something of which you should be extremely proud. And all of us ought to be willing to do whatever’s necessary not only to maintain it, but to see that it is enhanced.

Neuharth then added, noting that Gannett had paid $717 million to acquire the News, “More importantly, I think that also says that we will have some money left over with which to fund the future – fund the future – of this great newspaper.”[95]

As bottles of champagne were opened, the News staff believed they finally would have the resources to vanquish the paper “down the street,” but the moment was an illusion. The papers continue to lose money. The Free Press was in as bad a financial condition as its rival. In 1986 court papers revealed that the Free Press had been losing $10 million a year since 1980. Rumors had been whispered for many years that the News and the Free Press could not continue to lose money at this rate; either one would close or they would merge. Those rumors had long been answered with assurances that the locally owned News would never accede to a merger while the Knight–Ridder chain, which had bought the Free Press in 1940 from a local owner, would be equally stubborn in giving up a paper it had invested in both financially and emotionally to win the great Detroit newspaper war and overcome “the Snooze.”[96]

But in reality the war was coming to a quick end. The national press widely reported that one of the papers would soon close. Time Magazine ran a story about the Detroit newspapers under the headline, “Bitter Show-Down in Motown.” Gannett, with no vested local interest in the News, quickly approached Knight-Ridder chain, which owned the Free Press, with a plan. Knight-Ridder, having failed in two attempts to sell the financially troubled Free Press, was open to any reasonable suggestion. The two national chains began discussing a joint operating agreement for their Detroit papers. Negotiations were difficult but in April 1986 the chairmen of the two newspaper chains announced a Joint Operating Agreement (JOA) that would merge business, printing, and distribution operations of the two newspapers, and, although neither openly admitted it, bringing the long war between the News and the Free Press to an end. Although legal challenges to the agreement would eventually reach the United States Supreme Court, in the end the JOA was implemented.[97]

Despite the JOA, Detroit’s major dailies continued to suffer significant financial challenges. Symbolic of the continuing problems facing major metropolitan newspapers nationwide an the need to find a successful business model for mass market newspapers, the Detroit dailies announced in December 2008 that the papers planned to curtail home delivery and rely more on the internet. The plan called for home delivery to be curtailed to two days a week for the Detroit News and three days a week for the Detroit Free Press. At the same time the number of stories and features made available on the web were to increase. Whether this plan would work was not clear, but it clearly indicated the continuing efforts to save Michigan’s most well-known papers.[98]

Latter Hall of the 20th Century

As big city dailies struggled to survive many smaller daily newspapers and weeklies continued to enjoy financial health. The smaller papers that prospered usually built their success around the the “solemn truth” of George Booth that a large, metropolitan paper could not cover a local community better than a small, community-based newspaper.[99] Booth came by this observation through personal experience. In 1894 an effort had been made to launch a daily newspaper in Ann Arbor that was largely composed of type already set for the Detroit Daily Journal, seasoned with a bit of new local material. The Times of Ann Arbor, fearing that this combination might cause it to lose business, entered into a similar agreement with the Detroit News. Both ventures, however, failed rather quickly.[100]

Booth’s observation gave birth to several successful strategies for a profitable newspaper. One, of course, was Booth’s own strategy of creating versions of the Detroit News in smaller communities. This strategy, however, faced the same limitations and problems that beset all papers based on mass marketing in the last half of the twentieth century. An alternative strategy was a laser focus on local news. Whether published on a daily or weekly basis, this strategy was really a continuation of the old story of the small town newspaper. Isolated geographically from major metropolitan centers and with too small a population base to make financially successful another form of media, small town newspapers continued to serve as the principal vehicle through which the community obtained its local news and local advertisers made the community aware of their products. As the editor of the Frankenmuth News expressed the idea, speaking specifically about the paper’s coverage of World War II:

As it directly affects Frankenmuth shall we record the war. Other, abler journalists shall chronicle the swift march of the juggernauts of slaughter, other, keener pens shall inscribe the history our nation must write. Ours is the task, the ONLY one we can do; the one only WE can do of recording the history of one small village. That we shall do. And when this struggle is over, that history that we’ve written will not be one to be lightly dismissed as trivial. For war will be fought, treaty will be signed and war fought again. Tojo, Konoye, Hirohito will rise and die and other aggressors will usurp their place in history . . . but babies will be born, homes will be built, marriages will be made. Infants will be baptized; children will go to school; youth will grow into man’s estate … these things will go on and on . . . this is the history we propose to write during the black months that lie ahead.[101]

The Alpena News, celebrating their 100th anniversary in 1999, expressed the same idea more succinctly, “A community newspaper should be a mirror of that community and should chronicle the events that have shaped history.”[102]

Newspapers for Specific Groups

The third strategy revolved around publications designed to serve the needs of special communities not defined by geography but rather through some shared interest, characteristic, or concern. This was not a particularly new idea. In 1844 The Michigan Farmer had been established to report on subjects of interest to rural farmers. The Farmer had been followed by pioneering trade publications such as the Lake Superior News and Mining Journal (1846) the Peninsular Journal of Medicine, (1853), The Detroit Journal of Commerce (1865) and The Detroit Review of Medicine and Pharmacy, (1866).[109] One of the better documented of these early commercial papers was the Lumberman’s Gazette, published in Bay City between 1872 to 1885. The Gazette originally began publication as means to report on sawmill machinery but the paper quickly expanded to cover the industry as a whole. Although the paper originally had considerable trouble getting lumbermen to share data, as the paper gained circulation among investors lumbermen who wanted new cash for their firms became more willing to share information about their company. Like any industry publication the Gazette prospered or declined with the industry it covered, and by 1879 the paper was speculating that Saginaw river valley’s lumbering days were drawing to a close. In 1885 the paper ceased publication and the remnant of its assets were sold in 1887.[110]

Religious and social reform organizations also began to print their own weekly publications. The first such publication in Michigan appears to have been printed by the Seventh Day Adventists.. In November 1855, elder James White brought the already printing Adventist publications, The Review and Herald (first printed 1850) and the Youth’s Instructor (first printed 1852) to Battle Creek. The group added the Health Reformer to these publications in 1866. The first social reform publication in the state was the Home Messenger, which appeared in Detroit in late 1868 to benefit “the Home of the Friendless,” a charitable entity established to assist unwed mothers. Subsequently, the Baptists founded The Herald and Torchlight, in Kalamazoo in 1871. It was followed in 1872 by the Catholic, Western Home Journal. The Michigan Christian Advocate, a Methodist publication, appeared in 1875.[111] Among the most successful publications in this category, however, were the ethnic press.

Ethnic Newspapers

Throughout much of the nineteenth century, and into the twentieth, Michigan was the destination for many migrants seeking to make a new life for themselves. This legacy of immigration led to thirty-seven ethnic groups establishing more than 650 papers in the state. A 1978 survey counted found the 127 publications devoted to Germans the largest single group of ethnic newspapers in the state. Other groups with more than ten papers included:[112]

- Afro-American, 92

- Dutch, 73

- Polish, 64

- Finnish, 62

- Swedish, 43

- French, 36

- Ukrainian, 18

- Native American 17

- Arab, 16

- Hungarian, 14

- Jewish, 12

- Romanian, 12

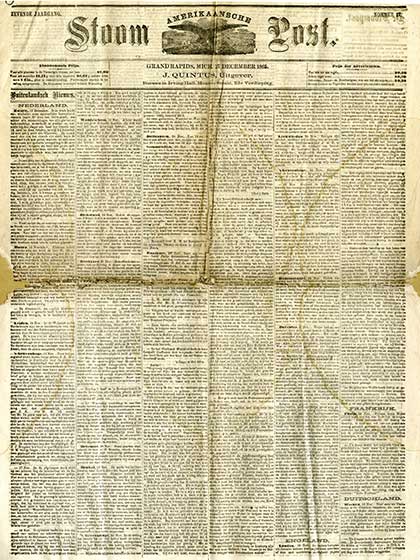

The German press demonstrates the typical cycle of foreign language publications. As German immigrants began to arrive in Michigan enterprising printers soon found a ready-market for German language publications. In the fall of 1844 Michigan’s first German language publication, Allgemeine Zeitung von Michigan appeared in the streets of Detroit. Like so much of the English-language press, this first German paper was intensely partisan, vigorously defending the interests of Michigan’s Democrats. One paper, however, was hardly enough for the rapidly expanding German population, that also had a strong Republican element. In 1866 it was estimated that about twenty percent of the state’s population had been born in Germany (200,000 out of 1 million). With such a large audience the number of German papers expanded rapidly. Between 1875 and 1900 German language newspapers peaked, with over 40 new newspapers founded in 15 communities. Detroit and Saginaw were particularly important as homes for the German press.[113]

World War I proved a turning point from which the German press in Michigan never recovered. Unsurprisingly, at the war’s outset most of the German press favored the cause of Germany. In August 1914 The Germania of Grand Rapids proudly proclaimed “Deutschland, Deutschland, uber Alles.” As the war dragged on, German papers complained more and more bitterly about “English propaganda” printed in the mainstream press. The general public, however, tended to believe as true what the German press labeled as propaganda. As a result, German papers grew increasingly isolated and also began to lose advertising. By the time the war began, the number of German papers had already begun to decline for financial reasons from their peak years, but the war greatly accelerated this trend. Grand Rapids Germania printed its last issue in March 1916. The final financial blow came in an Act of Congress passed in 1917 that required that foreign language papers supply exact translations of their war coverage to the local postmaster, until such time as the postmaster was convinced of the paper’s loyalty. The additional cost of filing English translations with the post office soon drove most of the remaining German papers into bankruptcy. By 1919, except for a few religious publications, only three German language newspapers continued to be printed in Michigan.[114]

Although

the German press was the state’s largest foreign language presence, the

Dutch press of western Michigan offers a good example of how the ethnic

press was different, yet the same, as the English language press.

Beside the obvious difference of printing in a language other than

English, the Dutch press included large sections of news about “the old

country.” These sections were often filled with long passages reprinted

from papers published in the homeland, coupled with nostalgic local

writing. Both strongly suggested an ongoing connection to the old land

and the “the old ways.” Dutch papers were more likely than English

publications to censor advertising found inconsistent with community

values. Ads for circuses, plays, or movies are conspicuously absent from

Michigan’s Dutch language papers before 1916, when one paper finally

began to print ads for movies. Ads for alcohol were treated carefully,

with the advertisement often noting the product was for “medicinal use.”[115]

Although

the German press was the state’s largest foreign language presence, the

Dutch press of western Michigan offers a good example of how the ethnic

press was different, yet the same, as the English language press.

Beside the obvious difference of printing in a language other than

English, the Dutch press included large sections of news about “the old

country.” These sections were often filled with long passages reprinted

from papers published in the homeland, coupled with nostalgic local

writing. Both strongly suggested an ongoing connection to the old land

and the “the old ways.” Dutch papers were more likely than English

publications to censor advertising found inconsistent with community

values. Ads for circuses, plays, or movies are conspicuously absent from

Michigan’s Dutch language papers before 1916, when one paper finally

began to print ads for movies. Ads for alcohol were treated carefully,

with the advertisement often noting the product was for “medicinal use.”[115]

Despite these important differences, the Dutch press in many ways reflected its non-Immigrant rivals. The Dutch press in the late nineteenth century tended to follow the lead of the American press, particularly in a predilection for sensationalism. There was also in some of the papers, particularly those that served smaller communities, an intense focus on local news that mirrored the concerns of small town local newspapers throughout the state. In general American politics were well reported and the papers and, like their English counterparts, during elections the papers featured lengthy, partisan opinions about the parties and the candidates. As in the non-ethnic press, Dutch editors engaged in vicious feuds, although in the Dutch community these were as often about religion as politics. Indeed the Republican De Grondwet (1860-1938) and the Democratic De Hollander (1850-1895),the colony’s first newspaper, spent most of the nineteenth century engaged in perpetual editorial warfare about politics, religion, and virtually anything else the two papers wrote about.[116]