One Room Schools

Several generations of Michigan children received their education in

one-room schools. In these small buildings students and their teachers

learned together. They shared a unique experience characterized by

camaraderie and personal challenge.

Despite their many successes, one-room schools were a

passing phase in American education. Dwindling rural populations and a

move to improve childhood education through consolidated schools, ended

the days of the one-room school.

Several generations of Michigan children received their education in

one-room schools. In these small buildings students and their teachers

learned together. They shared a unique experience characterized by

camaraderie and personal challenge.

Despite their many successes, one-room schools were a

passing phase in American education. Dwindling rural populations and a

move to improve childhood education through consolidated schools, ended

the days of the one-room school.

This

exhibit is divided into five sections. The first four explore the

teachers and their education, the experiences of the students, a typical

day in a one-room school, and the buildings themselves. The last

section, a bibliography, includes

an extensive listing of one-room school textbooks that are

found within the Clarke Library.

This web exhibit was prepared in July 1998 by Frank Boles and is based upon an exhibit regarding one-room schools that was shown in the Clarke Historical Library during the summer of 1998. That Clarke exhibit was curated by Evelyn Leasher of the Clarke Library and included material prepared by Laura Quackenbush for an exhibit on one-room schools mounted at the Leelanau County Historical Society.

A Day At School

A day in a one-room schoolhouse encompassed a wide range of events. The teacher was expected to arrive at the schoolhouse about an hour before the students. She was to draw water from the well, have lit a fire to warm the building, and often raised the flag. Typically, at 8:00 am the school bell was rung.

As the children were seated the teacher took attendance and then often began the day by reading to the students. In the nineteenth century the text read was almost always of a religious character, usually from the Bible. However, over time the morning reading evolved, first to "moral tales," and subsequently to significant works of fiction. For example, during the 1940's at the Frost School near Stanton teacher Veda Flinn began her school day by reading from Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House on the Prarie. Mrs. Flinn paced her reading of the volume so that the book was always completed on the last day of school. In some schools a song or two might also be sung before the day's studies began.

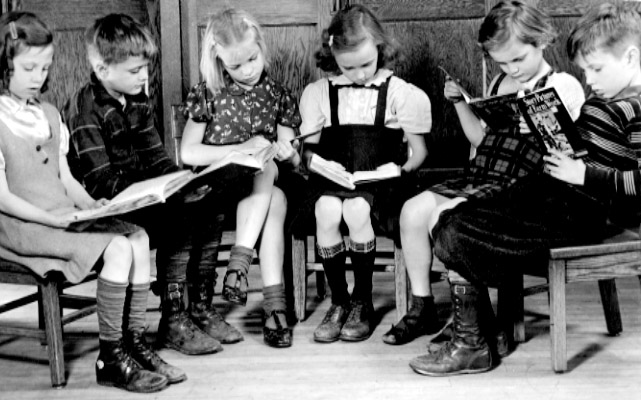

Class would then

begin. As the day progressed each class was called to the "recitation"

bench. There the teacher worked exclusively with those children for a

period, while the other students busied themselves studying or doing an

assigned lesson. Normally

there was a brief morning recess of about fifteen minutes, followed

by more classes, and then an hour for lunch. The afternoon was spent

much like the morning with classes and a short recess. At the hour of

afternoon recess, the younger students,

including the third graders, would be dismissed for the day. The

last hours of the school day was spent by the teacher working with the

more advanced fourth through eighth graders.

Class would then

begin. As the day progressed each class was called to the "recitation"

bench. There the teacher worked exclusively with those children for a

period, while the other students busied themselves studying or doing an

assigned lesson. Normally

there was a brief morning recess of about fifteen minutes, followed

by more classes, and then an hour for lunch. The afternoon was spent

much like the morning with classes and a short recess. At the hour of

afternoon recess, the younger students,

including the third graders, would be dismissed for the day. The

last hours of the school day was spent by the teacher working with the

more advanced fourth through eighth graders.

Students sometimes put the mixed age of their schoolmates to ingenious uses. One teacher recalls a student from the World War II era that she first believed had extraordinary reading skills. Each day she would write new words on the blackboard and each day, by the time "Doug's" opportunity to read came around, he had already learned the new vocabulary. Eventually she discovered that Doug was ingenious, but in a somewhat different way. Rather than industriously studying the board, each day he would quietly borrow the book from which the day's reading would be taken, look in the back where the new words were listed, and then ask one of the older students to help him with the day's new vocabulary.

"Unit" teaching was very popular technique well adopted to the one-room school. The teacher would select a topic, or unit, to study, such as pioneer days, trees, safety, or some other broad topic that each student could address at an appropriate level. Over time units evolved. For example in many one-room schools agriculture slowly gave way to science, physiology was replaced with health and hygiene. Students also would be united for various school events such as pageants or plays. Virtually every one-room school put on a Christmas pageant that was well attended by parents. The school was decorated with objects made by the children. The program often featured short poems or songs performed by the younger children and short plays enacted by the older students. The event would end with a holiday party in which gifts were often exchanged.

Although many students of one-room schools remember recess and the lunch hour as the highlight of the day, the time could be a harrowing experience for some children. Joyce Geasler, who taught in rural schools from 1923 to 1969, recalls an incident that occurred one day in the school sandbox:

A huge pocket of sand was on the play ground,

No greater place to play could ever be found.

I excused the little ones to go out and play,

And soon heard the death cry of a little stray.

There she stood in a hole two feet deep,

Screaming her fate in utter defeat.

Many little boys were feverishly filling her in,

They met my concerns with impish cries,

"We're only going to bury her alive."

The

fortunate teacher went home with her students, however many teachers

also performed the janitorial duties in the school. Thus, after the

day's classes had ended, the floor was swept, the room was straightened,

the teacher brought in fuel for the

next day's fire. At least once a week the teacher was expected

to scrub the floor. The teacher's janitorial responsibilities were,

however, often lightened by student helpers.

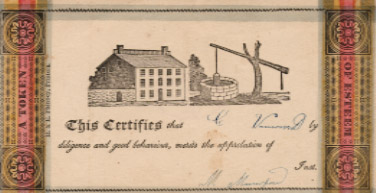

At the end of the year, teachers would

distribute "tokens" to their charges, along with their report cards and,

for a lucky few, their diplomas. The tokens, usually small,

inexpensively printed pieces of paper, were often among the most

cherished possessions

of students and a surprising number survive in the personal papers

of those who attended one-room schools.

At the end of the year, teachers would

distribute "tokens" to their charges, along with their report cards and,

for a lucky few, their diplomas. The tokens, usually small,

inexpensively printed pieces of paper, were often among the most

cherished possessions

of students and a surprising number survive in the personal papers

of those who attended one-room schools.

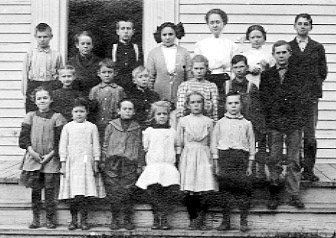

Teachers

Throughout much of

Michigan's past virtually anyone was allowed to teach, particularly in

rural schools. In rural districts the pay was always low and the school

teacher was often a young, unmarried woman, frequently still in her

teens. Johanna Smith

Rasmussen typified this trend. In 1924 she began teaching.

Throughout much of

Michigan's past virtually anyone was allowed to teach, particularly in

rural schools. In rural districts the pay was always low and the school

teacher was often a young, unmarried woman, frequently still in her

teens. Johanna Smith

Rasmussen typified this trend. In 1924 she began teaching.

The first day of school I was greeted by fourteen pupils. These were students in the sixth, seventh, eighth and tenth grades. Three were very near my own age. Somehow I was accepted as their teacher and we started learning together. It was a good year and truthfully I learned as much, if not more than my students.

Rural school teachers enjoyed neither vacation nor sick time. After state laws mandated a specific number of school days to be taught, rural teachers made up any absences by teaching extra days at the end of the school year. Rose Hamlin Tennis, who taught in various one-room schools in the mid-Michigan area, recalled how an appendicitis operation in mid-year closed school for several days which were made up in June.

Although some women made teaching their career, a substantial number of women taught for only a year or two, then married and moved on to new challenges. This pattern, as well as the relatively low pay given most one-room school teachers, led to very high turnover among teachers. By way of example, the Pleasant Hill School in Montcalm county had ninety-nine teachers in the eighty-six years the school operated, between 1873 and 1959.

Marriage was seen as a critical event that many local school boards tried to discourage until the end of the academic year. Many school boards required teachers to sign a contract granting the board authority to discharge a female teacher who married during the school year. Some contracts regulated the teacher's social life, required that she be at home by 8:00 p.m. unless later hours were explicitly approved by the school board and forbidding her from attending social functions other than those sponsored by the school itself or a church.

Teacher Education

At the beginning of the nineteenth century virtually anyone who wished to be a teacher could do so. As a consequence students were often subjected to teachers unprepared for the classroom. Charles A. Harper, in A Century of Public Teacher Education, pp 12-13, quotes Dr. Humphrey, president of Amherst College of in the 1820s and an early proponent of teacher education

I might quote their complaints till sunset, that it is impossible to have good schools for want of good teachers. Many who offer themselves are deficient in everything; in spelling, in reading, in penmanship, in geography, in grammar, and in common arithmetic. The majority would be dismissed and advised to go back to their domestic and rural employments, if competent instructors could be had.

Humphrey's frustration over poorly qualified teachers was caused, in part, by a fundamental shift in what he and other educational reformers of the early nineteenth century believed education should accomplish. "Schooling," as it was commonly understood at the beginning of the nineteenth century, was primarily memorization. Printed material was given the student to be committed to memory. The "teacher's" task was to help the child remember the printed word and test the student by holding the book while the child repeated the lesson from memory. In a system with such a modest goal, the teacher's own education could be quite modest, consisting of little more than literacy.

Educational reformers, however, wanted schools to go beyond memory and help children discover their potential. To accomplish this, reformers demanded more broadly educated teachers who could help children develop their individual skills. Re-inventing education as skill development rather than memorization originated in Germany and France but was quickly advocated by reformers in the United States. To accomplish their goal in America reformers realized the need for a school to educate teachers.

Massachusetts established America's first normal schools, in 1839. In 1849 the Michigan legislature voted to establish Michigan's first normal school, as well as the first such school west of the Appalachian Mountains. The legislature believed that by creating a more educated farmer better public school teachers would lead to greater economic prosperity. Although the legislature hoped for important results from the state's normal school, selection of the city in which it was to be located was based on more mundane considerations. After some debate the school was given to Ypsilanti, primarily because the community offered to raise $13,500 to help support the institution and was the highest "bidder" among the five communities seriously petitioning the legislature.

Although Michigan was the first "western" state to establish a normal school, it lagged behind other midwestern states in the development of such institutions. By 1880 Wisconsin had established four normal schools, while Minnesota had three. Michigan's second normal school was not founded until 1892. Located in Mount Pleasant, the school was primarily focused on educating teachers for rural school districts. The legislature quickly supplemented the newly formed normal school in Mount Pleasant with additional normals in Kalamazoo and Marquette.

The curriculum

offered at normal schools was of a practical bent. Future teachers

learned reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, grammar, spelling,

composition, and other subjects that would serve as the core of their

own teaching when they ventured

forth from the normal. Subjects such as music and drawing were added

to the curriculum in the 1870's, when it became clear that teachers who

could play an instrument or also offer art instruction could more

readily find jobs. Although the faculty

of traditional colleges often looked down on the normals because

they did not offer a classical curriculum, those involved in the normal

movement often took considerable pride in the fact that their schools

glorified common, everyday learning.

The curriculum

offered at normal schools was of a practical bent. Future teachers

learned reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, grammar, spelling,

composition, and other subjects that would serve as the core of their

own teaching when they ventured

forth from the normal. Subjects such as music and drawing were added

to the curriculum in the 1870's, when it became clear that teachers who

could play an instrument or also offer art instruction could more

readily find jobs. Although the faculty

of traditional colleges often looked down on the normals because

they did not offer a classical curriculum, those involved in the normal

movement often took considerable pride in the fact that their schools

glorified common, everyday learning.

In the twentieth century normal schools transformed themselves into teacher colleges. As colleges, the "normals" developed four year curriculums and were authorized to award degrees, rather than certificates. Michigan State Normal, in Ypsilanti, was among the first normals in the nation to accomplish the transformation into a college. In 1897 the state legislature designated Michigan State Normal a college and authorized the institution to confer college degrees. When the college granted its first bachelor's degree in 1905 it was the first normal school in the nation to do so. Despite this transformation into degree-granting institutions, teacher colleges in the first half of the twentieth century saw themselves as being distinguished from pre-existing state colleges and universities by their more limited mission. It was only in the latter half of the twentieth century, when higher education expanded in ways completely unanticipated by earlier generations, that many teacher colleges again transformed themselves, this time into universities that helped meet American society's seemingly unquenchable desire for a college education.

Although normal schools represented an important and eventually dominant trend in teacher education throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth century substantial numbers of teachers entered the teaching profession without the benefit of a normal school education. Low teacher salaries made it economically difficult for many future teachers to expend large sums of money obtaining teacher education. Taxpayers were at best ambiguous about improving the salaries paid to teachers or toward allocating money for normal schools needed only if one accepted the reformers new theory of education. As a result many alternatives to the normal school existed up until approximately 1940.

The two most common alternatives to attendance at a normal were teacher institutes and "county normals." Institutes were frequently sponsored by the normals themselves during the summer months. Institutes offered short, intensive periods of study in which rural teachers could obtain or refine their skills. Although some normal school faculty frowned on these "quick courses," through the 1920s they offered prospective teachers a quicker, less expensive way to begin their career.

County normals were similar to institutes but were usually organized by the county school commissioner with the assistance of the school districts in the county and the state. County normals were organized annually during the summer. They were ad hoc creations that offered very short courses focused on practical skills. County normals were often taught by only two "faculty members," an individual who delivered the "academic" instruction deemed necessary and a "master teacher" who offered practical advice. Because the courses were short, close to home, and often free if the student promised to teach the next year in the county, many young persons who could not afford to attend even a summer Institute at a normal school gained entry into the teaching profession through the county normal. County normal graduates were authorized to teach only in the county which had sponsored the normal, however in at least some instances counties recognized each others normal school as acceptable training and allowed graduates from one county to teach in another.

Students

Rural students often

experienced difficult family situations or extreme poverty, particularly

during the Depression. Ms. Tennis recalls one student who was being

raised by her older sisters, both her mother and father having died.

Another student came

to school one day excited by the "good dinner" he had eaten the

previous night. Thinking that the meal might have consisted of perhaps a

baked chicken, potatoes, a vegetable, and perhaps a pie or ice cream,

she was surprised to discover that the hearty,

home-cooked meal in question had consisted of cheese, crackers,

bologna, and beer. A third student's family was too poor to buy bread

and the student was too proud to attend school with only home-baked,

powder biscuits for lunch. To ease the student's

acute discomfort, Ms. Tennis made it a point to include powder

biscuits in her own lunchtime meal, thus making it acceptable for the

student to eat her own powder biscuits.

Rural students often

experienced difficult family situations or extreme poverty, particularly

during the Depression. Ms. Tennis recalls one student who was being

raised by her older sisters, both her mother and father having died.

Another student came

to school one day excited by the "good dinner" he had eaten the

previous night. Thinking that the meal might have consisted of perhaps a

baked chicken, potatoes, a vegetable, and perhaps a pie or ice cream,

she was surprised to discover that the hearty,

home-cooked meal in question had consisted of cheese, crackers,

bologna, and beer. A third student's family was too poor to buy bread

and the student was too proud to attend school with only home-baked,

powder biscuits for lunch. To ease the student's

acute discomfort, Ms. Tennis made it a point to include powder

biscuits in her own lunchtime meal, thus making it acceptable for the

student to eat her own powder biscuits.

Despite the sometimes difficult circumstances faced by students, many realized that their one-room school was a ladder of opportunity to what they saw as a better life. The opportunities afforded students could be measured both in terms of future job prospects and their future lifestyle. In 1931 Hazel Jorgensen Smith captured the essence of both these opportunities in an address she delivered, entitled, "Why I Want an Education."

One who is educated can appreciate and have a better understanding of art, music, nature, poetry and the finer things of life. You are better able to meet difficult situations. You can appear before a crowd and associate with the better class of people. You are happier in yourself and are more serviceable to others.

The young man or woman who is well-prepared to do a certain kind of work will find more demand for his work than the one poorly prepared... The one who is well prepared may command a larger income than one who is poorly prepared. Boys and girls of the grammar grade age often become uninterested in school because they think it is a waste of time. They are beginning to feel grown an they want to earn money. Facts prove that every day spent in school means more money when they finally go into the business and professional world. In the U.S. the average pupil who had finished the eighth grade earns $500 a year. The average high school graduate earns $1000 a year and the average college graduate earns $2000 a year.

For these reasons I am desirous of an education...

Students who attended one-room schools often developed both a sense of family as well as a keen realization of the opportunities made possible to them through education.

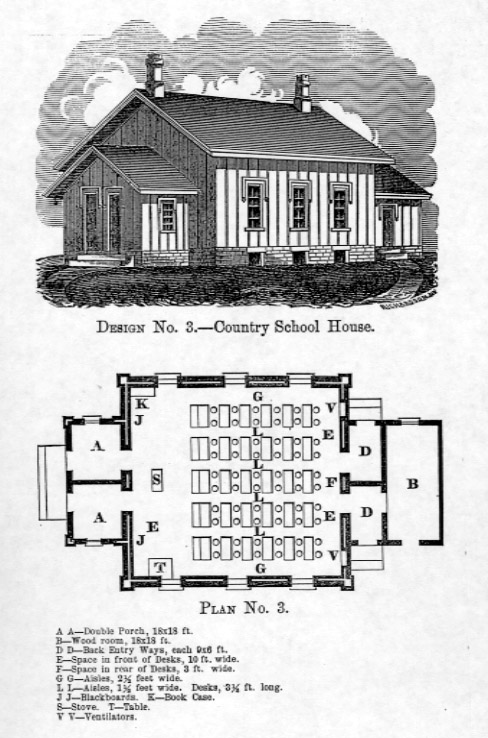

Architecture

Although simple buildings, one-room schoolhouses developed a distinctive architectural appearance. Almost invariably the first "schoolhouse" in a rural district consisted of a log cabin. The log cabin schools, while

minimally functional, really were not very well adopted to the needs of the students or teachers. As time passed new school buildings became similar to houses in their construction. The gabled vestibules and bell towers of frame schools also showed the

influences of church architecture. To help local school districts construct adequate buildings, by the 1890's, the state was issuing "standard" plans for rural schools.

Although simple buildings, one-room schoolhouses developed a distinctive architectural appearance. Almost invariably the first "schoolhouse" in a rural district consisted of a log cabin. The log cabin schools, while

minimally functional, really were not very well adopted to the needs of the students or teachers. As time passed new school buildings became similar to houses in their construction. The gabled vestibules and bell towers of frame schools also showed the

influences of church architecture. To help local school districts construct adequate buildings, by the 1890's, the state was issuing "standard" plans for rural schools.In 1914 the Michigan Department of Public Instruction asked that standard rural schools conform to various specifications. The buildings should rest on at least one-half acre of land, with trees and shrubs "tastefully arranged" about the building. Two "widely separated" outhouses or "indoor sanitary closets" should be provided for the student's use. The building should have a room heater and ventilator or basement furnace. The floors should be of hardwood and lighting should be so arranged so that neither the teacher nor the students should have to face into windows while doing their work. The state also called for "good blackboards, some suitable for small children," and "attractive interior decorations."

In the 1930's the federal government used Work Projects Administration (WPA) funds to make improvements in all "standard" one-room schools. These improvements included the installation of a furnace to replace room heaters, inside chemical toilets to replace those outhouses that remained, and windows on at least one wall of the building, usually situated so that the light would come in over the students left shoulders. The WPA standards of the 1930's remained more or less the standard for one-room schoolhouses when they slowly began to close in the 1950's.