The Hemingway Collection in the Clarke 2016 Exhibit

PREFACE

Of Course It’s Here! The Magic of Building, Maintaining, and Promoting The Clarke Historical Library’s Hemingway Collection is an exhibit almost twenty years in the making. It celebrates and tells the story of the library's successful development of an internationally recognized collection of material by and about Ernest Hemingway. But more than that, it tells the story of how it happened. People who use libraries rarely consider why what they ask for is waiting for them. But the Hemingway material in the Clarke came to be here not through luck or magic but rather through decades of work. An idea was created, it was nurtured, and it blossomed.

Over many, many years, key decisions were made, and important partnerships were established. These partnerships often grew into friendships. Money, a good deal of money, was raised. An endowment came into existence and continues to grow. But

very often, the money was only valuable because partnerships and friendships created unique ways to spend it; opportunities that would not have happened were it not for the library’s partners and friends.

Over many, many years, key decisions were made, and important partnerships were established. These partnerships often grew into friendships. Money, a good deal of money, was raised. An endowment came into existence and continues to grow. But

very often, the money was only valuable because partnerships and friendships created unique ways to spend it; opportunities that would not have happened were it not for the library’s partners and friends.

This catalog, in itself, is an example of the kind of collaboration and outreach that made the Hemingway collection grow. While I wrote much of the beginning, Marian Matyn is the primary author of the section on making the material available to researchers. Michael Federspiel described the collection today, and Janet Danek told of the exhibits and other outreach. Each of us wrote about what we knew best.

The exhibit and this catalog tell the story of how the library came to acquire a body of wonderful resources through the help of equally wonderful people.

- Dr. Frank Boles, Directorof the Clarke Historical Library

INTRODUCTION

Researchers who visit the Clarke Historical Library sometimes engage in magical thinking. They will ask a question or say that they’ve heard “somewhere” that the library has “some material” on their topic. A few minutes later,

as if by magic, just what they need will appear. The Clarke staff is often complicit in this, listening to the question, thinking for a few moments and perhaps consulting the online catalog, and then saying, “Well, you know these three books

and this manuscript collection would be good places to find that.” Researchers anticipate that the library staff will waive their wand (or more likely ask a student assistant to disappear into the stacks with call slips in hand) and the needed resources will appear.

Researchers who visit the Clarke Historical Library sometimes engage in magical thinking. They will ask a question or say that they’ve heard “somewhere” that the library has “some material” on their topic. A few minutes later,

as if by magic, just what they need will appear. The Clarke staff is often complicit in this, listening to the question, thinking for a few moments and perhaps consulting the online catalog, and then saying, “Well, you know these three books

and this manuscript collection would be good places to find that.” Researchers anticipate that the library staff will waive their wand (or more likely ask a student assistant to disappear into the stacks with call slips in hand) and the needed resources will appear.ERNEST HEMINGWAY AND HIS BIOGRAPHERS

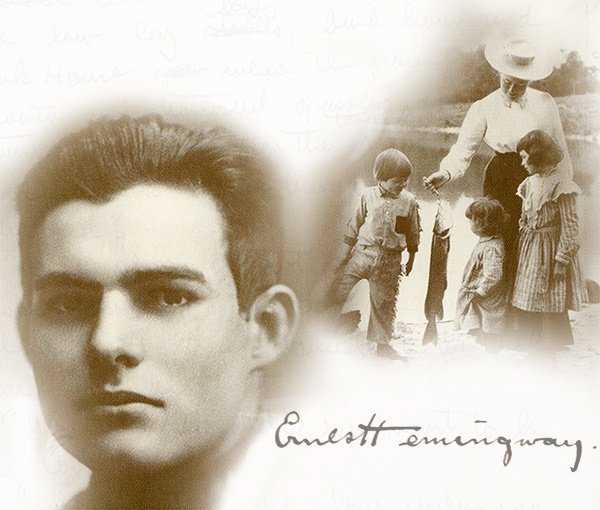

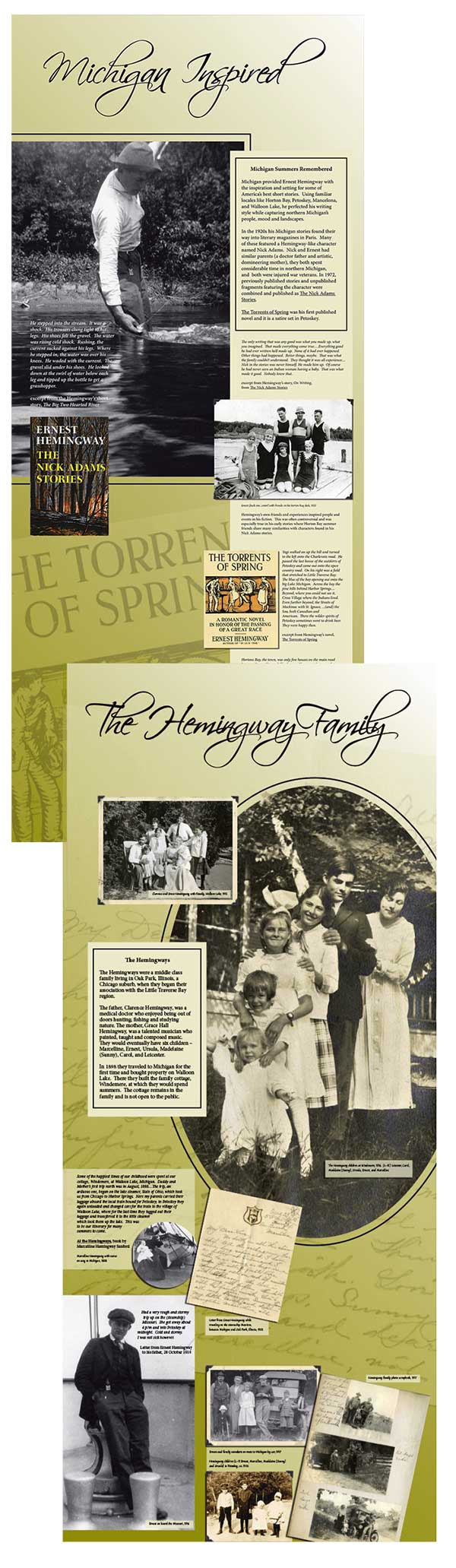

Unsurprisingly, there appeared a large body of literature discussing Hemingway’s life and works. But in reviewing the literature, there was an important gap. Ernest Hemingway, the Nobel-winning author, was described and dissected, but the young Ernie Hemingway, the boy who loved living in Michigan, was barely documented. Biographers invariably wrote a chapter that included a nod to Hemingway’s family, the summer home on Walloon Lake, and that Ernest Hemingway, world-famous sportsman, found the beginnings of his interest in hunting and fishing in those Michigan haunts.

The first summer Hemingway did not spend in Michigan was 1918, when he left the United States during World War I to serve overseas in the Red Cross. Wounded while distributing comfort items to troops along the front line, he spent an extended period in

Italy recovering from his injuries. When he returned home in 1919, he was a young man unsure of his future. College, he decided, was not for him. Agnes von Kurowsky, the woman he had met in Europe and thought he would marry, had unexpectedly ended

the relationship. He decided he needed to think, and he could do that best in Michigan. He spent much of 1919 and early 1920 in and around Petoskey. He began to write seriously and eventually left Michigan for Toronto and later Chicago, to try his

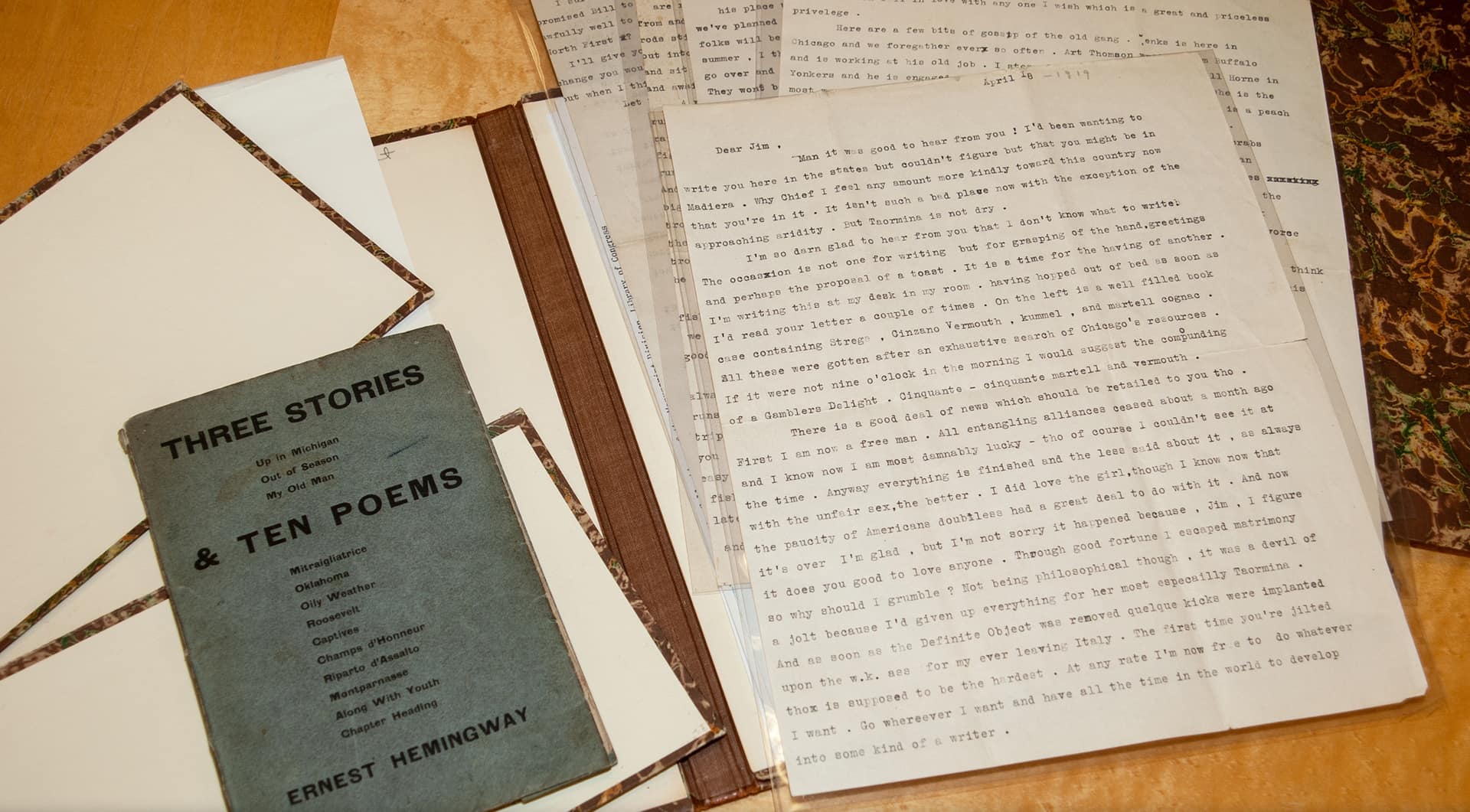

hand at journalism. Along the way he met Hadley Richardson. The couple were married in Horton Bay, and honeymooned in the Hemingway family cottage on Walloon Lake. Two months after their honeymoon, the couple moved to Paris. In 1923, he published

his first book in a privately printed run of only 300 copies. Three Stories and Ten Poems spoke to what Hemingway knew best at that time and what was closest to his heart. The first story in the book was entitled, “Up in Michigan.”

The first summer Hemingway did not spend in Michigan was 1918, when he left the United States during World War I to serve overseas in the Red Cross. Wounded while distributing comfort items to troops along the front line, he spent an extended period in

Italy recovering from his injuries. When he returned home in 1919, he was a young man unsure of his future. College, he decided, was not for him. Agnes von Kurowsky, the woman he had met in Europe and thought he would marry, had unexpectedly ended

the relationship. He decided he needed to think, and he could do that best in Michigan. He spent much of 1919 and early 1920 in and around Petoskey. He began to write seriously and eventually left Michigan for Toronto and later Chicago, to try his

hand at journalism. Along the way he met Hadley Richardson. The couple were married in Horton Bay, and honeymooned in the Hemingway family cottage on Walloon Lake. Two months after their honeymoon, the couple moved to Paris. In 1923, he published

his first book in a privately printed run of only 300 copies. Three Stories and Ten Poems spoke to what Hemingway knew best at that time and what was closest to his heart. The first story in the book was entitled, “Up in Michigan.”Although Ernie's youth was somewhat documented, there were people who thought the introductory chapters the biographers had written were incomplete. There were people in Michigan who realized something was missing. They found clues of how important Michigan remained to Hemingway in his later writings. In particular, they attributed considerable importance to Hemingway’s memoir, A Moveable Feast, published posthumously in 1964. They also recalled the many short stories written by Hemingway over the many years that were largely set in Michigan. The 24 tales and sketches, published in a variety of sources, were collected and republished in 1972 as The Nick Adams Stories.

Ernest Hemingway would travel widely and write stories set throughout the world. He would live for extended periods of time in France, Key West, and Cuba, with many lengthy excursions to other locations. But somewhere in the globe-trotting, paparazzi-followed author was an essential essence, formed when he was simply a young fellow named Ernie–later recalled by Hemingway himself as “Nick Adams.” That young man inhabited Ernest Hemingway’s past and informed his present, wherever he lived or visited and whenever he began to write.

Ernest Hemingway left Michigan in 1921, to return only once and then very briefly. However, he inherited the family cottage and kept it until his death. Michigan lived in the man and Walloon Lake held a place in his heart, influencing his work until his last days.

Although it is sometimes said that The Nick Adams Stories were autobiographical, Hemingway himself suggests strongly that this is not true: “All good books are alike in that they are truer than if they had really happened, and after you are finished reading one, you will feel that all that happened to you and afterwards belongs to you: the good and the bad, the ecstasy, the remorse and sorrow, the people and the places and how the weather was. If you can get so that you can give that to people, then you are a writer.” - Ernest Hemingway

THE BEGINNING

If there were printed clues in the 1970s about the importance of Michigan in the life of Ernest Hemingway, there was only one small reference in The Nick Adams Stories that went

into detail. The people who remembered Ernie and who understood how Ernest drew on that younger iteration of himself eventually gathered together. In 1990, they formed the Michigan Hemingway Society (MHS). The group sponsored an annual conference

in Petoskey devoted to Hemingway and had a natural focus on Michigan. Early on, a few members of this group realized that, while meeting once a year had many benefits, it did not create a documentary legacy of Hemingway’s years in Michigan.

Someone, somewhere should nurture and grow an institutional home for research material about Hemingway in Michigan.

If there were printed clues in the 1970s about the importance of Michigan in the life of Ernest Hemingway, there was only one small reference in The Nick Adams Stories that went

into detail. The people who remembered Ernie and who understood how Ernest drew on that younger iteration of himself eventually gathered together. In 1990, they formed the Michigan Hemingway Society (MHS). The group sponsored an annual conference

in Petoskey devoted to Hemingway and had a natural focus on Michigan. Early on, a few members of this group realized that, while meeting once a year had many benefits, it did not create a documentary legacy of Hemingway’s years in Michigan.

Someone, somewhere should nurture and grow an institutional home for research material about Hemingway in Michigan.

The documentary task was really twofold. The first was to document Ernie Hemingway. Finding what existed would be challenging, as unlike the already well-documented, prolific writer, Dr. Clarence's son was not going to have a large body of manuscript material documenting his days on Walloon Lake. Bringing what did exist into a collection would involve persuasion, persistence, and perhaps a good deal of money as literary manuscripts created by Nobel Prize winners command a very high price at auction, even if they were written when the author was only fourteen.

The second challenge was more subtle. Young Ernest Hemingway was not writing about Michigan but rather absorbing experiences, learning how the world worked and how people lived. Thus, to understand Ernie Hemingway, one had to understand the corner of the state that served as his classroom. A thorough documentary heritage of the Little Traverse Bay area was essential to contextualize and explain what the young Hemingway experienced.

One of the members of the MHS who understood the problem and was looking for a place to house a Hemingway collection was Michael Federspiel. Then a teacher in the Midland Public Schools, Federspiel was a Central

Michigan University alumnus who had worked in the Clarke Historical Library as an undergraduate student. He wondered if the library might be interested in developing a Hemingway collection. Federspiel brought to the table more than an interest. He

also had a hook. He had amassed a substantial personal collection of Hemingway-related material that, if donated, could serve as the basis for a collection documenting Hemingway generally, with an ongoing focus on Hemingway in Michigan.

One of the members of the MHS who understood the problem and was looking for a place to house a Hemingway collection was Michael Federspiel. Then a teacher in the Midland Public Schools, Federspiel was a Central

Michigan University alumnus who had worked in the Clarke Historical Library as an undergraduate student. He wondered if the library might be interested in developing a Hemingway collection. Federspiel brought to the table more than an interest. He

also had a hook. He had amassed a substantial personal collection of Hemingway-related material that, if donated, could serve as the basis for a collection documenting Hemingway generally, with an ongoing focus on Hemingway in Michigan.Frank was thinking about how important a collection like this might be to the library, as well as if there really was the time, the staff, and the money to make it happen. Although Mike’s collection was a good start, it was only a start. Much of the most important material had to be found, and once found, he knew literary manuscripts sell for high prices. The Clarke had never seriously collected the papers of an award-winning artist, and collecting an artist with the stature of Ernest Hemingway would be learning how to swim by jumping into the deep end of the pool.

Still, Mike was persuasive about the opportunity at hand. He also had become president of the Michigan Hemingway Society. In that role, he knew many people who would be key in successfully developing this project. He was learning what records existed and who owned them. He could also serve as a library ambassador and character reference. Put rather simply, he could confirm that those Clarke people were okay, seriously

interested in building a Hemingway collection, and could be trusted while in your home to refrain from stealing any of the silverware.

Still, Mike was persuasive about the opportunity at hand. He also had become president of the Michigan Hemingway Society. In that role, he knew many people who would be key in successfully developing this project. He was learning what records existed and who owned them. He could also serve as a library ambassador and character reference. Put rather simply, he could confirm that those Clarke people were okay, seriously

interested in building a Hemingway collection, and could be trusted while in your home to refrain from stealing any of the silverware. Mike also put one other enticement on the table. He offered the beginnings of financial support through the creation of an endowment to help underwrite those expensive purchases that likely would have to be made sooner or later. Such an endowment that makes possible continued collection growth is the key to the ongoing success of this kind of collection, and the key, as well, to the heart of a library director.

Frank was interested, but before fully committing, he also engaged in conversations about the project with then Dean of University Libraries, Tom Moore. Opportunity comes with risk. Years might be spent working on a project, but like any collecting project, there was always the possibility that all of that time and energy would lead to naught. Collection development in a special collections library is a gamble. It’s a gamble that Frank suggested taking, and Tom later encouraged.

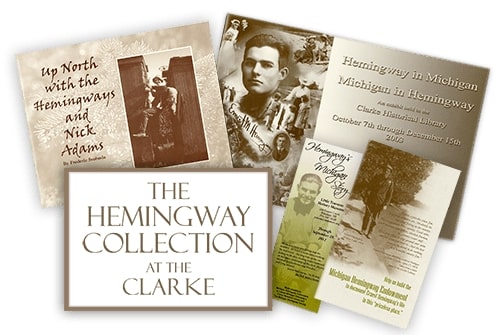

A decision had been made to at least try and develop a Hemingway collection, and in the summer of 2002, Mike Federspiel made his first of what would eventually become many donations to the Clarke. That first gift consisted of approximately 400 items. He also made an initial pledge to start an endowment supporting the ongoing growth of the project. With a gift, an endowment, and great ambitions, the logical decision was to promote the Hemingway collection through an exhibit.

THE FIRST MAJOR PURCHASE

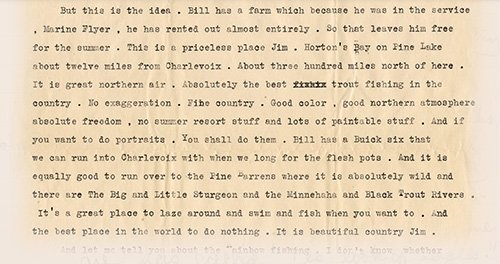

Just as plans developed for the 2003 Hemingway exhibit, an extraordinary item appeared on the auction market—the Jim Gamble letter. Gamble had been Hemingway’s commander in Italy during World

War I, where the two had become friends. Gamble had invited Hemingway to spend time in Italy with him, but Hemingway had returned to America. In the spring of 1919, Hemingway wrote Gamble with a similar idea but a significant twist: Gamble, Hemingway

suggested, should come to the United States and spend the summer with him around Little Traverse Bay. To persuade his former commander to make the trip, Hemingway wrote several pages describing the delights of Michigan. The letter’s glowing

descriptions of what Gamble would experience made clear just how much Hemingway loved northern Michigan. For a “Hemingway in Michigan” collection, the letter was a “got to have” item.

The Clarke staff bid on the

Gamble letter, but the library was not successful at the auction. Since auction houses do not reveal the identity of the buyer, Frank Boles sent a letter to the auction house and requested that it be forwarded to the buyer. The letter asked if the

buyer would loan the document to the Clarke for the upcoming exhibit.

To his surprise, Boles received a prompt reply and learned that the letter had not been bought by a collector but rather by a book dealer. The dealer was not interested

in loaning it, but after further communication, he agreed to sell it for a profit. It was a moment in which the future of the enterprise hung in the balance—did the library grow the collection by purchasing a key letter or accept that key documents

were beyond its financial reach and the collection that had been dreamed about would never be.

It was time to see if the additional money could be raised, but in the end the Clarke staff came up short. With no likely prospects left, Dean

Moore looked at what had been done, thought over the possibilities, and perhaps those conversations with Frank about the project, and made a decision. He called a donor he knew, explained the situation, and asked for the final gift needed to fund

the purchase. The donor made the commitment. It was the first of many important purchases to come, all of which were financed with private funds.

The 2003 exhibit also forged a relationship between the library and Hemingway family members who still lived in the Petoskey area. Two nephews of Hemingway lived in the area and both owned significant, Michigan-related Hemingway material. Both men agreed to loan important items for the exhibit. It was clear that both men were interested in what the library was doing, but neither was convinced to either donate or sell to the library the items they owned.

Although the Hemingway family reserved judgment, the exhibit helped bring in other new donations of material, as well as gifts to the endowment. Among the most important was establishing a formal relationship with the Michigan Hemingway Society. The Clarke received two gifts of original material. One was eleven diaries written by George R. Hemingway, Sr., Clarence’s brother. The other was a group of Horton Bay photographs, gathered together by William Ohle and given to the Society. Collectively, this began a working relationship between the Society and the Clarke. The library had successfully set off on a journey with an important partner, but the road ahead would be measured in years. Persistence is a necessary hallmark in growing the collection.

In 2006, one of the two family members living in Michigan decided to sell his Hemingway material—more than 100 items—in a private sale. It was another great opportunity to grow the collection, but it came with several challenges. The seller wished to sell the collection as a single lot and not divide it up for individual sales. The overall value of the material was far more than the Clarke could afford to pay, and most of the items were not of interest as they were not about Hemingway's life in Michigan. Only four items were thought to be critical for the Clarke’s collection:

• An early typed “newsletter” written by “EMH and TH” that talked about the boys’ hunting

exploits, believed at the time to be Hemingway’s first “publication.”

• An unpublished, incomplete story written by Ernest while in high school and set in Michigan.

• A four-page letter written in June 1919 by Ernest to his father talking about the cottage and his

• A postcard sent in August 1919 by Ernest to his father while Ernest was on a fishing trip in the

Upper Peninsula, a trip that would be the basis for one of his best-known short stories.

Not intimidated by other institutions with considerably greater resources who could possibly purchase the entire body of material, Frank took an offer to the owner that was in the interest of the Clarke, and not necessarily in the interest of the seller. Would he, as a favor to the library, and to help keep Michigan-related Hemingway material in the state, sell the four items in which the Clarke was interested separately, despite already expressing the desire to sell the entire collection to a single buyer?

It was another one of those key moments, much like the effort to buy the Gamble letter. This time, the library had enough money to buy what it wanted, but not enough money to buy the broader collection. The library needed to benefit from the goodwill of a family member. To great relief and lasting gratitude, the owner withdrew the four items of interest from the overall sale, and sold them to the Clarke separately.

DOCUMENTING UP NORTH

The Hemingway collection was growing in important ways, but there remained an overall weakness in the library’s ability to document Hemingway in Michigan.

The library’s collections could talk about Hemingway, but they lacked the resources to describe the family’s experience as “summer people.” Quietly increasing the amount of material on hand documenting the region,

the library’s holdings nevertheless lacked visual material. But if the library had a gap in its photographic holdings, the staff

The Hemingway collection was growing in important ways, but there remained an overall weakness in the library’s ability to document Hemingway in Michigan.

The library’s collections could talk about Hemingway, but they lacked the resources to describe the family’s experience as “summer people.” Quietly increasing the amount of material on hand documenting the region,

the library’s holdings nevertheless lacked visual material. But if the library had a gap in its photographic holdings, the staff

also knew where the needed resource was located, and that its owner also had a problem—one the Clarke could help fix. The Little Traverse Historical Society had a superb visual collection about Petoskey and the nearby region. Housed in a converted 19th century railroad depot overlooking the Bay, the Society’s home lacked air conditioning in the summer and was closed and without heat in the winter. The organization was desperately in need of help preserving their massive photography collection.

In the fall of 2008, Mike Federspiel, who knew both the Society’s collection and the organization’s staff and leadership, brokered a deal that was a benefit to the Society and the Clarke. The Clarke would scan the Society’s

extensive photographic collection. The Clarke’s copy of the scans vastly enhanced the documentation about Hemingway’s experiences in the region found in the library. The Society, in turn, gained a security copy of their images, and

importantly, a place where researchers could see the images during the winter months when their building was closed. The first batch of photos scanned numbered approximately 2,000. Eventually, almost 5,000 images were scanned.

For several

years, the work of collecting and scanning went on quietly and small additions were made to the collection. Frank visited with the members of the Michigan Hemingway Society each year at their annual meeting to report on the organization’s archives

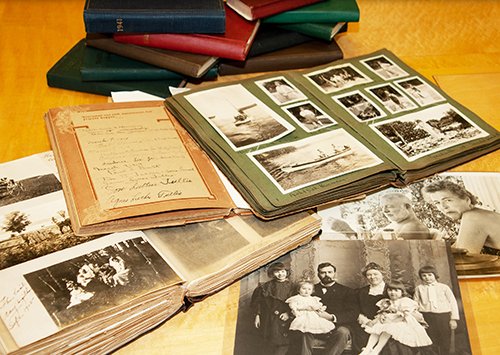

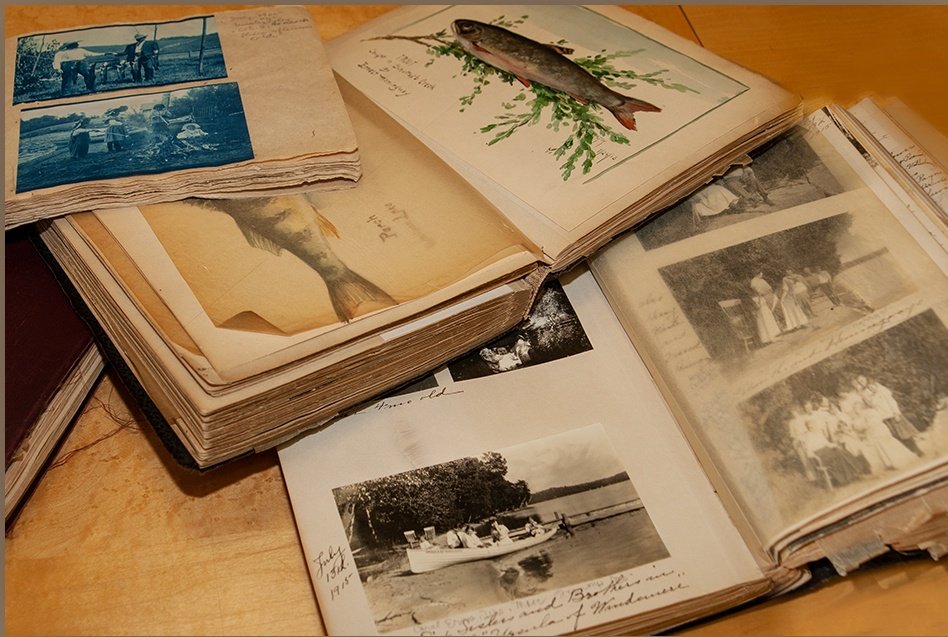

and foster relationships with friends and acquaintances. There was a lull in collecting significant new material until March of 2013, when a scrapbook, created by Ernest's mother, Grace Hall Hemingway, went on the auction block. The scrapbook had

been created by Grace for her daughter Ursula and included additional family photos.

NEW MATERIAL

The news that the Ursula scrapbook was to be auctioned broke suddenly and late. The auction house was not well-known for handling literary manuscripts and the library staff learned about the sale only a few days before the auction was to take place. There was not much time to find the needed funding, but years of building relationships with people interested in Hemingway paid off.

Dean Moore had demonstrated a commitment to help with funding by drawing from

Friends of the Libraries money when it was needed. Frank contacted the Dean’s administrative aide, and said that he needed to talk to Tom “today!” about the auction. The Dean’s calendar was booked solid, but they

were able to find ten free minutes. The conversation with Tom was not a long one, but after years of working together to develop the collection it was easy to convey both the opportunity and the need in a few words. After a few moments of thought,

the Dean once again gave approval for the critical financial support that was needed.

The library was the successful bidder at the auction. The auction was important not just because the scrapbook was added to the Clarke’s Hemingway collection. The purchase of the scrapbook also answered a question that, for years, had hung

over the even-more-interesting scrapbooks Grace Hall Hemingway had created—scrapbooks that remained in Michigan. When the Ursula scrapbook sold at auction, it established a market value for Hemingway family scrapbooks.

The Jepson purchase, although successful, also made clear that the Hemingway Endowment needed to be substantially increased. Hurried phone calls to likely donors and finding brief moments in Dean Moore's busy schedule made for interesting tales, but it also meant never knowing if there was enough money on hand to make sudden purchases. In July 2013, the library launched a campaign to increase the Hemingway Endowment’s principal from $41,000 to $100,000. The goal was challenging, but by this point, it was also possible to point to a solid track record of success when asking for donations. Today, the endowment principal stands at $97,969, with several legacy bequests that will eventually be received.

With a market value for a Grace Hall Hemingway scrapbook established, the staff made the decision to approach the second family member of Ernest who lived in Michigan about the idea of a purchase/gift of the Marcelline Hemingway Sanford scrapbooks and other family material. The library had a long and increasingly close relationship with the relative, actually housing the material in the Clarke for many years, while he retained ownership.

This was, yet again, another crucial moment that depended not only on having money in hand, but having earned the trust and goodwill of a member of the Hemingway family. The scrapbooks, as well as the family papers, were the single greatest treasure that was still in the state. The scrapbooks told, in pictures and captions, the entire story of Ernest Hemingway’s Michigan years. After some discussion, a friendly deal was struck for a combination purchase/gift. The scrapbooks, as well as the family papers, became the library’s in April 2016.

In April 2018, another extraordinary opportunity to add to the collection appeared. A first edition of Hemingway’s first book, Three Stories and Ten Poems, was put up for auction. The first short story in the small publication, “Up in Michigan,” made it clear what the young Hemingway thought he knew best and could write about. Once again, with the help of the Endowment, the Dean, and a few key friends, the library was able to obtain one of only 300 original copies of the book.

MAKING THE MATERIAL AVAILABLE TO RESEARCHERS

Bringing Hemingway material into the library was the first step, but there was a great deal of work that needed to be done between the acquisition of material and making it available to researchers. Processing material as diverse as that describing Ernest Hemingway and his family involved much more than simply putting a book on the shelf or handing a Hemingway letter to a researcher. The most challenging materials to deal with are the unique items that were never published.

PHYSICAL PROCESSING

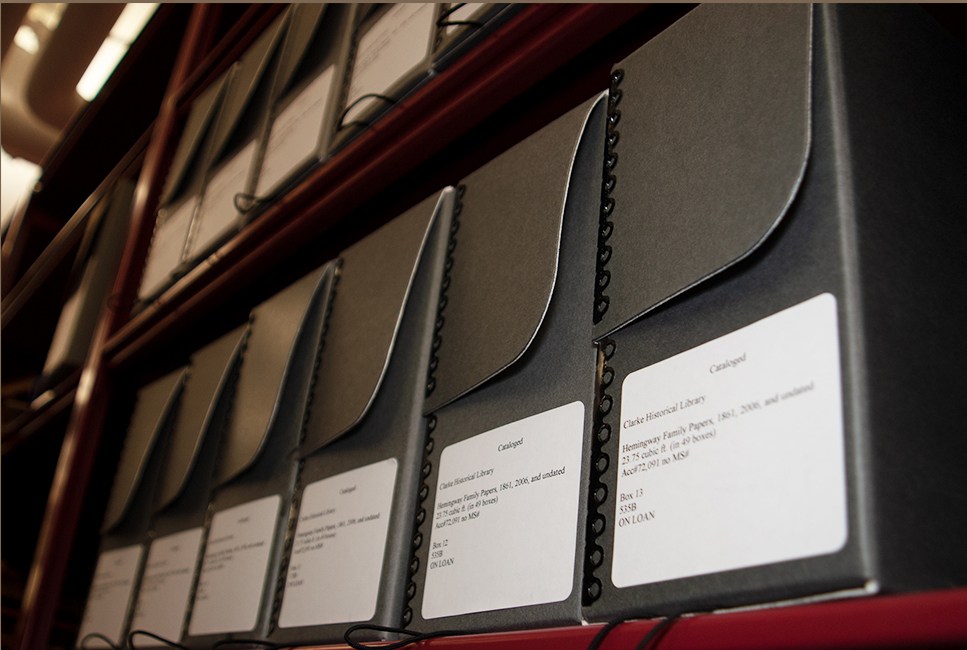

The physical processing of a collection with as much important material as found in the Clarke regarding Ernest Hemingway, involved many steps. Along the way, careful notetaking was necessary to be sure important details could be recalled later when it became time to describe the collection intellectually. The first goal is always to retain the existing order of the material or, if necessary, impose a new, easy to understand, logical order. Once an order was established, the Hemingway collection received detailed physical examination.

The physical examination accomplished several purposes. It removed any material that was not of research value. Things that are not of long-term importance were removed, such as duplicate items, blank pages, or papers that were illegible. Physical

examination also removed things that threatened the long-term preservation of the material. These included pins, rubber bands, and sticky notes, any of which could deteriorate the material. In addition, as a matter of routine, acidic or faded

materials that had important information but lacked “associational value,” for example a useful newspaper clipping, were photocopied. The copy was kept in place of the original material. Items with associational value could also be

copied if they were acidic or faded, but in those cases the original item was also maintained, for example, an original letter written by Ernest Hemingway to which time has not been kind.

INTELLECTUAL DESCRIPTION

The written finding aid must also be uploaded to the web and made searchable so Google and various online librarytools can retrieve the information. Using the finding aid as a guide, the last step in description is to create an original catalog record

that can be found both in the CMU Libraries’ system and in databases nationwide. The catalog record is a highly technical endeavor requiring yet more research and following often complicated and occasionally arcane library cataloging and

naming conventions. Processing the pieces that collectively make up the Hemingway collection was challenging. Because the collection trickled into the library from many people over more than a decade, there are multiple Hemingway-related primary source collections. Even

when the pieces f

The written finding aid must also be uploaded to the web and made searchable so Google and various online librarytools can retrieve the information. Using the finding aid as a guide, the last step in description is to create an original catalog record

that can be found both in the CMU Libraries’ system and in databases nationwide. The catalog record is a highly technical endeavor requiring yet more research and following often complicated and occasionally arcane library cataloging and

naming conventions. Processing the pieces that collectively make up the Hemingway collection was challenging. Because the collection trickled into the library from many people over more than a decade, there are multiple Hemingway-related primary source collections. Even

when the pieces f it together into one collection, processing was complicated.

it together into one collection, processing was complicated.

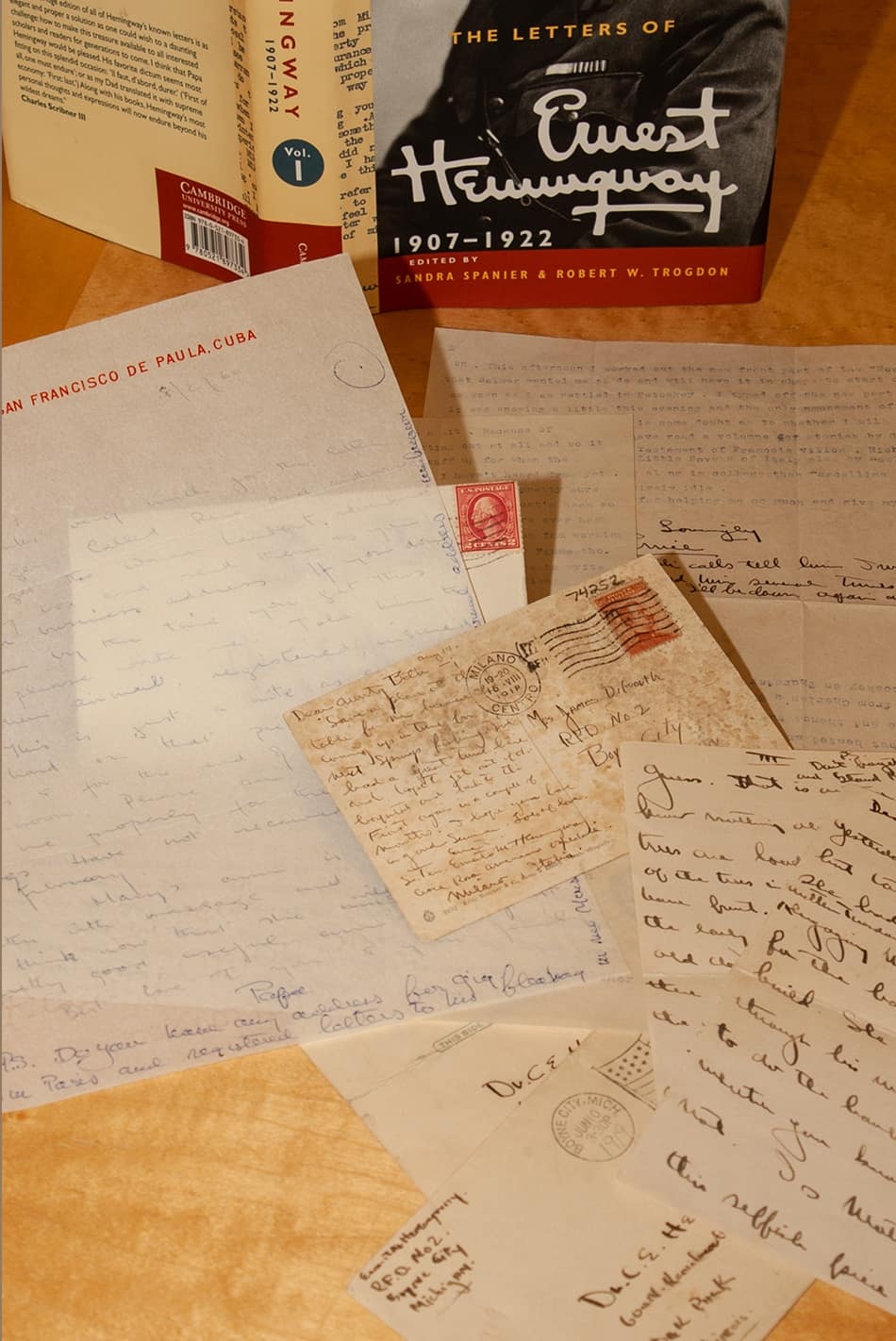

The largest single set of documents found among those about Ernest Hemingway is the Hemingway Family Papers. Today housed in 49 boxes, it was substantially unorganized when it arrived at the library. What exactly would be found within the documents

was uncertain. Much of the collection consisted of handwritten, multi-page letters, each folded, usually in quarters, inside small envelopes. Many letters were enclosed inside of other letters, and in some instances there were four “layers”

of letters in a single envelope. It required careful work to retain these intricate relationships while unfolding all of the letters and storing them in acid-free folders to give them the best possible preservation environment. Because much of

the correspondence was with classmates, friends, or distant relatives of the Hemingways—people who were not quickly identifiable—it was also necessary to research these people to understand their relationships with the various Hemingway

family members they had written to or received letters from and provide context for researchers.

The largest single set of documents found among those about Ernest Hemingway is the Hemingway Family Papers. Today housed in 49 boxes, it was substantially unorganized when it arrived at the library. What exactly would be found within the documents

was uncertain. Much of the collection consisted of handwritten, multi-page letters, each folded, usually in quarters, inside small envelopes. Many letters were enclosed inside of other letters, and in some instances there were four “layers”

of letters in a single envelope. It required careful work to retain these intricate relationships while unfolding all of the letters and storing them in acid-free folders to give them the best possible preservation environment. Because much of

the correspondence was with classmates, friends, or distant relatives of the Hemingways—people who were not quickly identifiable—it was also necessary to research these people to understand their relationships with the various Hemingway

family members they had written to or received letters from and provide context for researchers.

THE COLLECTION TODAY

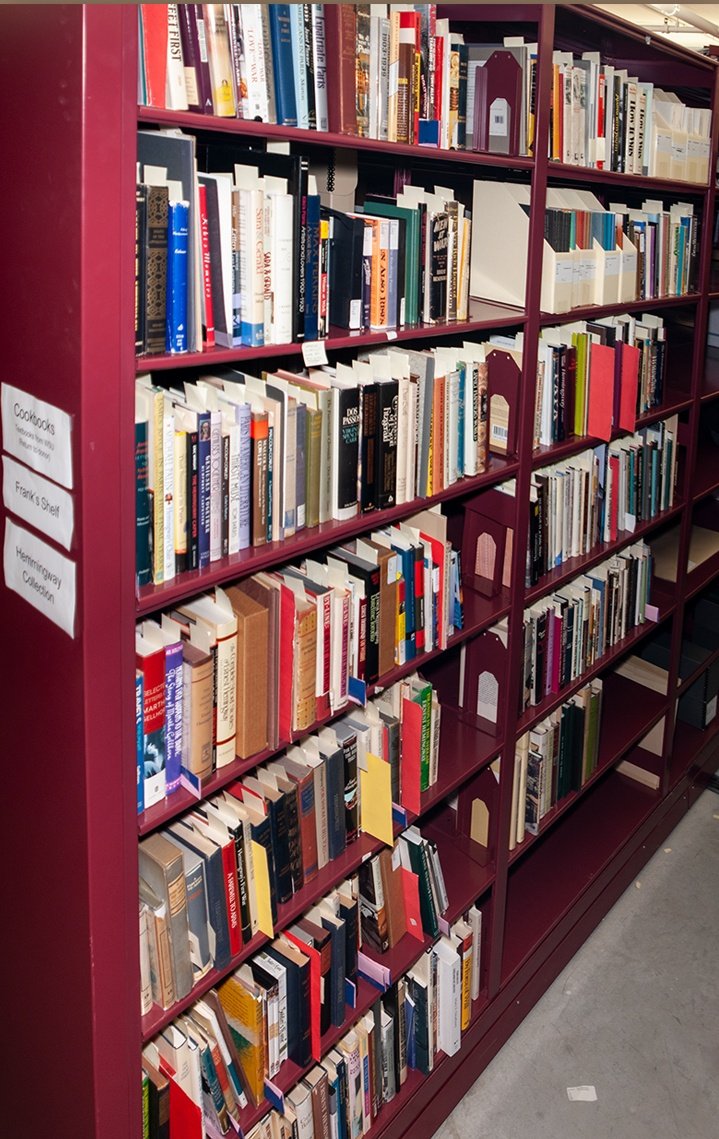

Today the Hemingway collection consists of a wide variety of material.

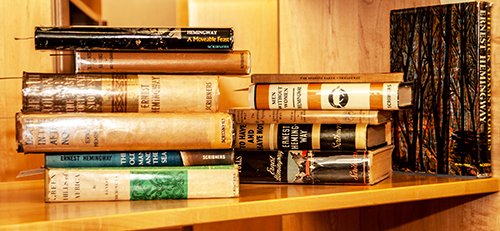

It concentrates most heavily on Hemingway’s personal and literary connections to Michigan, but also has a wide selection of first, international, and rare editions of his works, dozens of biographies and books about the locations in which he lived

and about which he wrote, along with various movie and other forms of ephemera. The most significant items are those directly associated with Ernest and his immediate family. These Hemingway items, coupled with the Clarke’s vast holdings of

materials about northern Michigan in the years the Hemingways called it their summer home, make the Clarke Historical Library a one-of-a-kind Hemingway collection.

As to be expected, the collection is rich in books and articles written by Hemingway himself. He wrote ten novels, twenty story collections, nine works of nonfiction, and dozens of stories published in magazines such as Life, Esquire, Look, Ken, and Cosmopolitan. The collection has first-edition examples of almost all of these and they range from small, privately printed Paris magazines with his earliest Michigan stories to posthumously published novels edited by others. The crown jewel of the first editions is undoubtedly Three Stories and Ten Poems. Printed in a limited edition of 300 copies in Paris in 1923, it begins with his controversial “Up in Michigan” story. Set in fictional “Hortons” Bay, Michigan, the story so graphically described a sexual episode on a Lake Charlevoix dock that it is said Hemingway’s own parents refused to have the book in their home. Three Stories and Ten Poems was a prelude to a career writing distinguished novels. As his fame increased, his first editions became international bestsellers as foreign publishers joined American printers in making his work available. In Cuba, where he is a national hero, El Viejo el Mar (The Old Man and the Sea) has been published several times.

Hemingway’s most famous short story,

The Big Two Hearted River, is particularly well represented in the collection. In addition to a copy of

This Quarter, the Paris based magazine in which it was originally published in 1926, the library has extremely rare copies of fine art print editions. Published in very limited quantities, one version even includes an original watercolor

fishing painting. Complementing the published versions of

The Big Two Hearted River found in the collection is an original postcard Ernest sent his father from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula when he was on the fishing trip that inspired the story.

Perhaps no other American writer has had so much written about him as Ernest Hemingway. The Clarke holds over 250 books and magazine articles chronicling his life, which range from full-length biographies to short feature articles in mainstream and pulp magazines. Especially interesting are the articles in 1950s emerging men's magazines where his larger-than-life macho portrayals sold magazines to people hungry to hear of his alleged exploits. He also inspired books written about the locales where he lived and those about which he wrote. On the Clarke's shelves, one can find volumes associated with his life experiences in Oak Park, Michigan, Paris, Spain, Africa, Cuba, and Idaho.

A particularly interesting subset of the Hemingway collection is the movie-related ephemera. His stories and books resulted in 17 film adaptations beginning with 1932's A Farewell to Arms starring Gary Cooper and Helen Hayes. Over the decades, leading stars such as Ingrid Bergman, Spencer Tracy, Ava Gardner, Richard Beymer, and Humphrey Bogart all portrayed Hemingway-created characters. To promote these films, the movie studios launched elaborate publicity campaigns that featured striking posters of various sizes and lobby cards to entice the public into theaters. Campaign manuals filled with clip art, text for advertisements, and marketing suggestions were sent to distributors and theaters urging them to focus as much on the fact that the film was associated with Hemingway as the A-list movie stars the film featured. Supplementing these manuals were publicity photos showing the stars in engaging scenes. The Clarke's collection of these items is colorful and comprehensive. It includes international posters and programs and even movie material not based on any literary work but instead Hemingway himself.

The printed material and movie-related items constitute a strong Hemingway collection, but the personal papers associated with Ernest Hemingway himself and his immediate family found in the Clarke are what make this collection a world-class resource

for those looking to better understand Hemingway’s formative experiences here in Michigan.

The printed material and movie-related items constitute a strong Hemingway collection, but the personal papers associated with Ernest Hemingway himself and his immediate family found in the Clarke are what make this collection a world-class resource

for those looking to better understand Hemingway’s formative experiences here in Michigan.

Collectors have caused original manuscripts in Hemingway’s own hand to be among the most sought after, selling for thousands of dollars. It is estimated that in his life (a time before tweets, instant messages, and emails) Hemingway composed over six thousand typed and handwritten letters. The Clarke is home to six of them. All but one in the library relate to his Michigan experiences. The six-page, typed letter to his World War I superior, Jim Gamble (1919) gushes with descriptions of Michigan summers. Another letter informs his family of securing a Petoskey boarding house room where he hoped to write; an earlier letter updated his parents on the harvest at their northern Michigan farm. While these were not written to the famous people the established author would come to know, they nevertheless give intriguing insights into how his Michigan experiences influenced him.

The library is also the home of two examples of his unpublished, juvenile fiction. One is

The Sportsman’s Hash, a fishing story written and illustrated when he was 10 years old. The other is a longhand multi-page story set in Michigan lumber camps written when he was in high school. Both of these are examples of the

hold Michigan had on the young man’s imagination.

The library is also the home of two examples of his unpublished, juvenile fiction. One is

The Sportsman’s Hash, a fishing story written and illustrated when he was 10 years old. The other is a longhand multi-page story set in Michigan lumber camps written when he was in high school. Both of these are examples of the

hold Michigan had on the young man’s imagination.

In addition to these Ernest Hemingway items, the library also has an extensive group of personal papers and photo scrapbooks from his sister, Marcelline Hemingway Sanford. The albums, created by Grace Hall Hemingway, the mother of Ernest and his siblings,

show that the Hemingway family’s Michigan summers were much like summer vacation today. Among other things, photos show the family fishing, entertaining guests, swimming in the lake, and boating. These albums document the Hemingways' first

Michigan trip in 1898 through Marcelline and Ernest’s high school graduation in 1917. They are particularly interesting in that the images are annotated by Grace Hall Hemingway. This adds greater depth to the stories and personalities of

those shown.

The Hemingway Family Papers includes far more than those photo albums. In addition to them, are early family correspondence and numerous items associated with the publication of Marcelline Hemingway Sanford’s memoir, At the Hemingways, in which she told her version of her relationship with her brother. These papers, along with Marcelline’s photo scrapbooks, give fascinating insights into the Hemingway family and its most famous member, Ernest.

While not a member of the immediate family, “Uncle George” Hemingway was a summer and eventually year-round resident at Lake Charlevoix. His family’s guest books and his diaries tell of family guests and visits. Along with the Hemingway Family Papers, they allow us to learn about the family that raised and influenced Ernest.

EXHIBITS AND OTHER OUTREACH

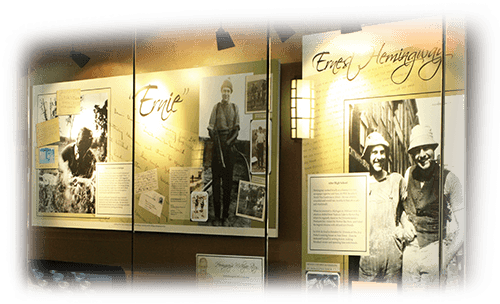

As with all of the resources held by the Clarke, the Hemingway collection does not fulfill its purpose until it is used. Creating an awareness of what is available in the collection is a continuous challenge. Library descriptive tools are critical, but also limited in their reach. Marketing the collection beyond the library is important to inform researchers and those who can help the collection grow of the treasures found here. In addition, marketing demonstrates to existing donors how their contributions are being used and helps plant a seed within those who might make future donations of material or support the Hemingway endowment.A particularly effective method in promoting the library’s Hemingway collection has been through exhibitions. Exhibits are many things. The public often thinks of them as opportunities for education and entertainment. Through creative interpretation of the materials held by the library, exhibits inform audiences, pique interest, and encourage further exploration. Exhibitions also serve as the foundations upon which the library’s future can be strategically built. They can promote programming including speakers, publications, documentaries, events, and collaborations, all of which increase the audience of particularly interested individuals and build new relationships. To take advantage of these opportunities, the library has developed a variety of Hemingway-themed exhibit experiences, each have focused on a unique aspect of the collection.

PAST EXHIBITS

Hemingway in Michigan, Michigan in Hemingway, was the initial exhibit created by the library to introduce Hemingway enthusiasts and scholars to the Clarke Historical Library, its holdings, and the library's long-term ambitions.

The 2003 show was well attended. Especially welcomed were the many members of the Michigan Hemingway Society. The Gamble letter, loans of rarely seen, family-owned material, and one of only three authenticated fly rods used by Ernest Hemingway were exhibited. Additionally, an exhibit catalog was published. The combination of experiences, collaborations, and print material demonstrated the ways in which the Clarke was becoming Hemingway's Michigan home.

Hemingway in Michigan, Michigan in Hemingway, was the initial exhibit created by the library to introduce Hemingway enthusiasts and scholars to the Clarke Historical Library, its holdings, and the library's long-term ambitions.

The 2003 show was well attended. Especially welcomed were the many members of the Michigan Hemingway Society. The Gamble letter, loans of rarely seen, family-owned material, and one of only three authenticated fly rods used by Ernest Hemingway were exhibited. Additionally, an exhibit catalog was published. The combination of experiences, collaborations, and print material demonstrated the ways in which the Clarke was becoming Hemingway's Michigan home.then distributed without charge to every public high school in Michigan.

• A companion study guide.

• Publication, in print format, of Hemingway's Michigan: A Driving Tour of Emmet and Charlevoix

Counties, researched and compiled by Ken Marek.

• A website to house the driving tour information.

• A capstone project to place a state historical marker at Walloon Lake, celebrating Hemingway's

Michigan roots.

The $30,000 funding request associated with the package exceeded the Council's funding cap. It was assumed that, if the application was successful, the Council would choose among the six projects. Instead the Council waived their funding cap, funded

all six proposals, and requested key parts of the package be delivered in 90 days. The Great Michigan Read kick-off event would be held at Petoskey's Crooked Tree Arts Center (CTAC), and the Council planned the event to include an enhanced version

of the Clarke's now-funded Hemingway traveling exhibit, catalog, and documentary film.

In 2012, the library was offered another unique opportunity to use the Hemingway collection for outreach. The International Hemingway Society chose to hold their biennial conference in the Little Traverse Bay region, bringing an international audience of approximately 600 guests to explore and experience “Hemingway’s Michigan.” As part of the conference, the library staff mounted different exhibits in three venues around the Bay, and cooperated again with WCMU television to create another documentary, Into the North, which focused on the tourist experience in the Little Traverse Bay area between 1890 and 1920, largely the years the Hemingway family came to summer.

The first and simplest task was to place the traveling exhibit created in 2007,

Up North with the Hemingways, back in Petoskey. This time the show was placed in the Carnegie Library Building administered by CTAC. This building was where, in 1919, the young Ernest had made a public presentation about his wartime

experiences, and thus a “must see” for the conference attendees. That exhibit also showcased four “treasures” from the Clarke to dazzle the attendees. They included two stories in Hemingway’s hand, written when

he was a youth, the Gamble letter, which had been a focus of the 2003 exhibit, and the postcard written by Ernest to his father while fishing in the Upper Peninsula, part of the trip immortalized in the short story,

The Big Two Hearted River.

Second, the exhibit that had been shown in spring 2012 in the Clarke’s galleries, A Delightful Destination: Little Traverse Bay at the Turn of the Century, was reinstalled in the Harbor Springs Area Historical Society, across the bay from Petoskey. This exhibit featured some of the many photographs the library had copied from the Little Traverse Historical Society. Components of that exhibit remain in the area, currently on display in the Emmet County courthouse in Petoskey.

THE ERNEST HEMINGWAY COLLECTION AT THE CLARKE

The library’s newest Hemingway exhibit continues the library’s longstanding efforts to promote the Hemingway collection, while offering an opportunity to reflect on how “the magic”—from envisioning a collection to building

exhibits—comes into existence. An exhibit can be many things: educational, entertaining, interactive, or immersive. But what a good exhibit is not is a book on the wall. Nor is it a comprehensive history. Exhibits capture and communicate

the essence of a story, pique the interest of visitors, and inspire further learning.

The library’s newest Hemingway exhibit continues the library’s longstanding efforts to promote the Hemingway collection, while offering an opportunity to reflect on how “the magic”—from envisioning a collection to building

exhibits—comes into existence. An exhibit can be many things: educational, entertaining, interactive, or immersive. But what a good exhibit is not is a book on the wall. Nor is it a comprehensive history. Exhibits capture and communicate

the essence of a story, pique the interest of visitors, and inspire further learning.

The library staff creates two new exhibits each year for the Clarke. Each is a custom exhibit designed using unique criteria established only for that exhibit. The concept is developed, content is researched, techniques are established, components are designed, graphics are acquired, text is written, AV treatments are developed, and final design specifications are created. Then, the exhibit is fabricated and finally, it is installed. Each task is done once and each time it is a brand-new experience with new content and new components. This was the process followed for the current exhibit.

The foundation of the exhibit design process is based upon the answers to several key questions, which require careful thinking about the purpose of the exhibit. The answers to four questions became the foundation for everything that followed:

1. Why create this new Hemingway exhibit?

2. Who is the audience?

Everybody is not an acceptable answer.

Before beginning, one must determine for whom the exhibit is being designed. An experience created to inspire a 16-year-old may not satisfy a college student or a Hemingway scholar, and vice versa. While the Clarke’s primary purpose is to serve CMU and the success of the student body, the staff determined that, in addition to this goal, the library’s donors and Hemingway enthusiasts should be the primary focus for this exhibition. The hope was to honor donors, attract enthusiasts and scholars, and give insights to CMU students about Hemingway and the Hemingway collection, as well as how professionals in the field of special collections and exhibitions do their jobs.

3. What is the exhibit’s specific objective?

With two prior exhibits discussing the same general subject, it was necessary to determine how this exhibit would be different from past exhibitions. A custom-designed exhibit, by definition, seeks to create a “unique and extraordinary” experience. The content should be based on a storyline only the Clarke can tell and which it has not told in the past, to assure visitors a unique experience. If a visitor has seen it before, or can find it elsewhere, why would they bother to come and see it here?

4. Storyline research and “The Gems”

After establishing the exhibit objective, one must identify primary materials, sources, text references, and generally “fill in the blanks” regarding the exhibit’s content. This step was less difficult for this exhibit than it sometimes can be. Mike Federspiel, who has helped guide collecting efforts since the beginning of the initiative, served as curator. Mr. Federspiel’s knowledge about Hemingway and of the library’s collection served the work well. If there was a question, Mike could answer it.

EXHIBIT TEXT - EVERY WORD MUST EARN ITS KEEP

Exhibit text is unique. Just as a successful exhibit must deliver only the essence of a story, so must the text. Experience proves extensive text discourages visitors from reading beyond the headlines. But the task of writing a text block in 125 words is always challenging, for an author invariably has 1000 words of stories to tell. Because the team who built this exhibit had prior experience working together, they understood the value of brevity and, if at times a bit begrudgingly, delivered concise, effectual interpretive text.

VISION OF EXPERIENCE AND THE JOY OF INSTALLATION

And every exhibit has “the moment.” The moment is when the joy and excitement of seeing all the pieces come together is tempered by the discovery of a typographical error, a missing panel, or some unanticipated problem. The more exhibits that are created, the less likely “that” problem will come up again. But like sunrises, inevitably, a new problem emerges. Resolving it with little time and working with only the material in hand involves quick thinking, going a bit outside the box, and improvisation—skills the smiles on an opening night may conceal, but later make for great stories.

TWENTY YEARS IN THE MAKING

While library staff look forward to that use, as well as to continued growth and outreach through exhibits and other tools, those who work in the library acknowledge and thank those who, over two decades, have helped make the Hemingway collection possible. The Michigan Hemingway Society and many of its members have become long-term partners and good friends through the project. Many generous friends have made decisions that greatly benefited the library, while others have donated items to the library. Still others have made financial contributions to enable the library to make important purchases and grow the endowment. The importance of this financial support, sometimes on short notice with requests for not-small amounts of money and other times asking the same individuals to help build the principal of the endowment to continue the work, cannot be overstated. All of this happened through large amounts of goodwill and the help of good friends who the Clarke staff hopes will continue to work with the library in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Although key colleagues in the creation of this endeavor informed me that my name would be listed as the author, an honor I accepted for the convenience of library catalogers everywhere, the exhibit and this catalog are very much a collaborative work rather than the creation of a single individual. I would like to Janet Danek, the University Libraries Exhibit Coordinator, Michael Federspiel, a recently retired fixed-term faculty member of the CMU History Department, and Marian Matyn, Clarke Historical Library Archivist and associate professor, each of who wrote parts of this catalog. Many of the best words you have read in this publication are theirs.

My thanks also go to Bryan Whitledge and Kimberly Chiodo for proofreading this document. The mistakes that remain are mine and not theirs.

Finally, it would not have been possible to publish this work without the hard work of Kari Chrenka, Coordinator of Marketing and Branding within the University Libraries. Her official title gives little clue to her substantial abilities to design and produce printed publications, for which we are all grateful.

- Dr. Frank Boles, Director of the Clarke Historical Library

To learn more about the Endowment, visit clarke.cmich.edu/HemingwayEndowment

MISSION OF THE CLARKE HISTORICAL LIBRARY

The Clarke Historical Library collects, preserves, and promotes nationally recognized collections, that include:

- The history of Michigan and the Old Northwest Territory.

- The history of Central Michigan University.

- Selected topics, including exemplary children’s literature, campaign biographies of United States presidential candidates, the history of angling, and historic Michigan newspapers.