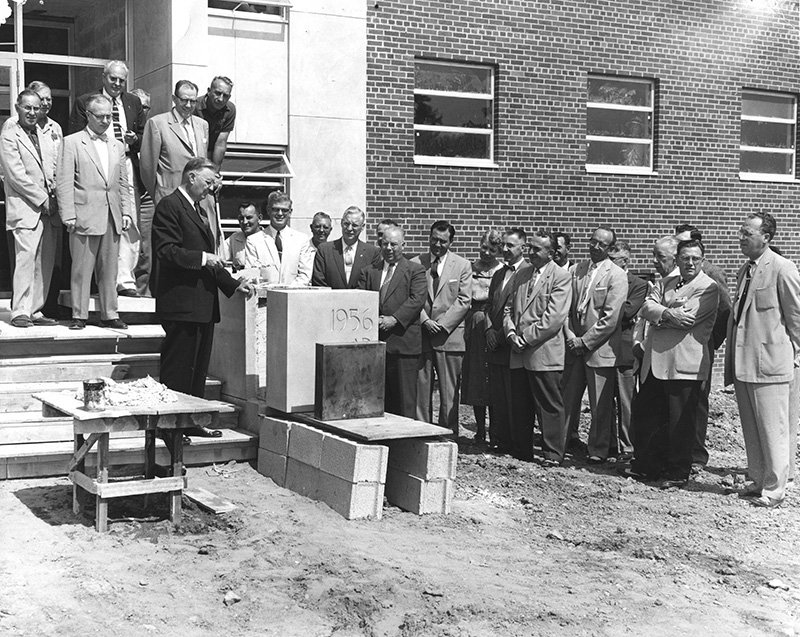

Demolished Buildings

1. Heating Plant II (1941-1990)

2. Vetville [Sheep Sheds II] (1946-1957)

3. Home Management House (1949-1974)

4. Off Campus Education [Field Services] (1953-1976)

5. Old Central Hall Physical Training Building (1909-1974)

6. Old Main [The Normal] (1893-1925)

7. "Temporary Buildings" [Sheep Sheds I] (1925-1952)

8. Training School (1902-1933)

9. Heating Plant I (1905-1948)

10. Bertha Ronan Residence Hall (1923-1970)**

15. Old Theunissen Stadium (1949-2001)

16. Rowe Hall East Wing (1958-1998)

17. Football Office (circa 1960's-1974)

18. President Emeritus House [Anspach's Home] (1959-circa 1970s)

19. Preston Court Apartments (1954-1995

20. Center for Economic Expansion & Technical Assistance (1963-1969)

21. Campus Security [DPS I] (1964-1970)

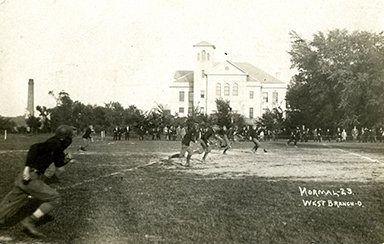

22. Tambling Field (1921-circa 1940s)

Heating Plant II (1941-1990)

Opened: 1941 Closed: 1990 Cost: $125,000

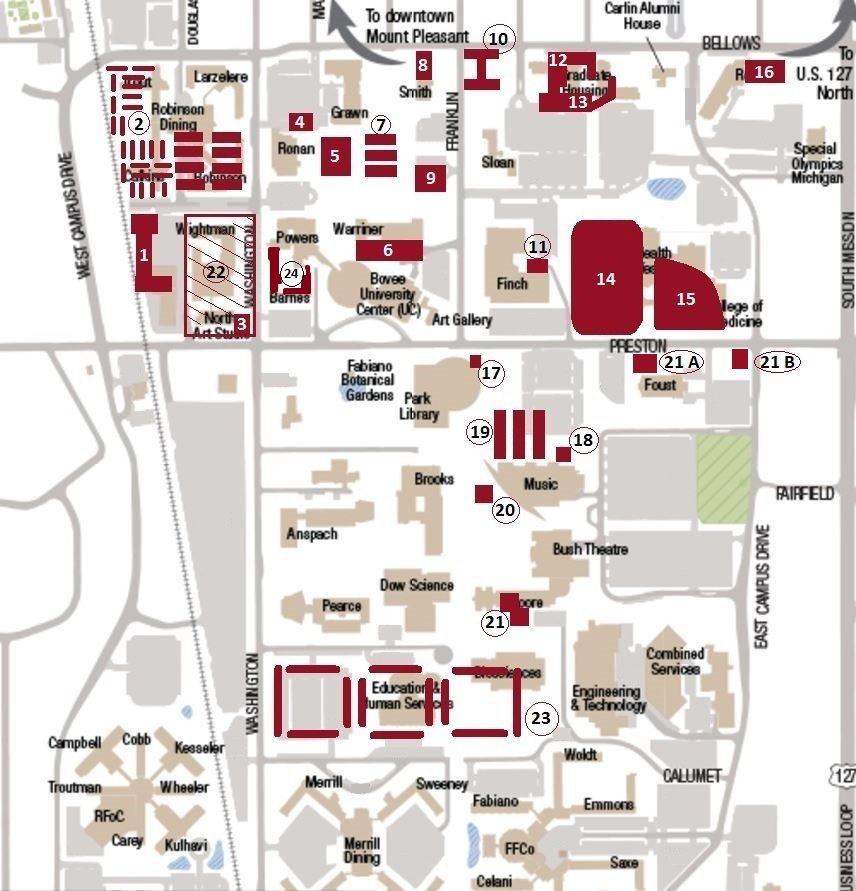

The building that would eventually become West Hall was originally built as a heating plant (seen along the railroad tracks, with a smokestack, in the image to the right), a replacement for the first plant built on campus in 1905. Planning for a

replacement heating plant began in the late 1930s, and in May 1941 the State approved $125,000 for the project. The building would be constructed in a corner of the girls' athletic field, east of the railroad tracks, to facilitate the delivery

of fuel. Designed by Roger Allen of Grand Rapids and built by the Miller-Davis Company of Kalamazoo, the building featured a 150-foot smokestack. Construction began in the summer of 1941. The new plant was tied into the existing tunnel system,

although crews had to build several new tunnels, including the addition of a large tunnel in front of Keeler Union and Warriner Hall. By the fall of 1942, the new plant was up and running. A $270,000 renovation was carried out in 1949, which included

the addition of a large new boiler and water softeners, as well as the construction of a new stack with an economizer to maximize efficiency. The new heating plant remained in operation until the early 1960s.

The building that would eventually become West Hall was originally built as a heating plant (seen along the railroad tracks, with a smokestack, in the image to the right), a replacement for the first plant built on campus in 1905. Planning for a

replacement heating plant began in the late 1930s, and in May 1941 the State approved $125,000 for the project. The building would be constructed in a corner of the girls' athletic field, east of the railroad tracks, to facilitate the delivery

of fuel. Designed by Roger Allen of Grand Rapids and built by the Miller-Davis Company of Kalamazoo, the building featured a 150-foot smokestack. Construction began in the summer of 1941. The new plant was tied into the existing tunnel system,

although crews had to build several new tunnels, including the addition of a large tunnel in front of Keeler Union and Warriner Hall. By the fall of 1942, the new plant was up and running. A $270,000 renovation was carried out in 1949, which included

the addition of a large new boiler and water softeners, as well as the construction of a new stack with an economizer to maximize efficiency. The new heating plant remained in operation until the early 1960s.

The building in which the plant was housed was designed with limited office space and Facilities Management occupied part of the building since the 1940s. In 1951, garage space was added to the facility. When the new Central Energy Facility was constructed in the early 1960s, the boilers were removed and the old heating plant was remodeled into more office space, as well as maintenance garages and storage for Facilities Management. The complex, which consisted of the large building that had been the physical plant as well as a collection of smaller garages and sheds (the "sheepsheds" (SEE VETVILLE SECTION) left over from a postwar housing community on the site), remained the home of Facilities Management and the Motor Pool until the 1980s.

With the completion of a new Combined Services Building in 1990, Facilities Management was relocated to the east side of campus and the old heating plant building was left vacant. The University demolished most of the building at a cost of $340,000, leaving only the northern end of the structure standing. This building, which became known as West Hall, became the new home of CMU Media Relations, University Communications or UComm today. Media Relations had been housed in 114 Rowe Hall, but that office complex had become too cramped for the department's purposes. Although University officials discussed moving Media Relations into the space formerly occupied by the bowling alley in the University Center, it was ultimately decided to utilize the newly vacated space in West Hall. Renovation of the office complex cost $20,000 and was complete by December 1990. The new office space provided more room and privacy for the four departments of Media Relations—the news bureau, publications, photography, and sports information services.

Vetville [Sheep Sheds II] (1946-1957)

Opened: 1945 Closed: 1958

![Vetville [Sheep Sheds II]](/images/default-source/academic-affairs-division/clarke-historical-library/explore-the-collection/explore-online/cmu-history/buildings-on-campus/demolished-buildings/20210921_cmuhistory_demobuildings_002946d4cdc-9fa2-48e6-8f5d-0080a08b116b.jpg?Status=Master&sfvrsn=7a653bc7_3) The establishment of the GI Bill had an important impact on both the student population and the buildings on campus. With the rapidly increasing numbers of veterans attending Central and other schools around the state and nation, administrators looked

for inexpensive housing units that could be easily constructed. An additional issue involved married veterans, who represented the first large group of students with families on campus. With this in mind, large trailers began arriving on Central's

campus in 1945. Designed as temporary housing for married veterans, a total of 12 trailers were installed on the property cornered by Bellows and Washington (north of present-day Wightman Hall and on the site of the present-day northwest quad). Moline

Construction of Clare was awarded the contract for the construction of the trailer units. Perhaps the most memorable part of living in this temporary housing was the condition of the roads and walkways between the trailers. As one GI put

it in a CM Life interview, "the only complaint I have so far is that the GI Bill should include row boats or water wings—just try and get out of those trailers!"

The establishment of the GI Bill had an important impact on both the student population and the buildings on campus. With the rapidly increasing numbers of veterans attending Central and other schools around the state and nation, administrators looked

for inexpensive housing units that could be easily constructed. An additional issue involved married veterans, who represented the first large group of students with families on campus. With this in mind, large trailers began arriving on Central's

campus in 1945. Designed as temporary housing for married veterans, a total of 12 trailers were installed on the property cornered by Bellows and Washington (north of present-day Wightman Hall and on the site of the present-day northwest quad). Moline

Construction of Clare was awarded the contract for the construction of the trailer units. Perhaps the most memorable part of living in this temporary housing was the condition of the roads and walkways between the trailers. As one GI put

it in a CM Life interview, "the only complaint I have so far is that the GI Bill should include row boats or water wings—just try and get out of those trailers!"

In June of 1946, the temporary trailers were replaced by more solid, albeit still temporary, facilities. With the help of the Federal Public Housing Authority, nine 32-man dormitories were installed to house single veterans. The Quonset hut-style buildings, each 20 feet by 100 feet, were made of metal and shipped from Marion, Ohio. These buildings were placed on the west side of Washington north of Hopkins Avenue, with the ends of the buildings facing Washington. In addition to the dormitories, 26 two-family apartment buildings were built on the site. With room for up to 52 married veterans and their families, each unit consisted of a living room, kitchenette, two bedrooms and a bath, as well as appliances for heating, cooking, and refrigeration. The family units were installed to the west of Douglas Street between Hopkins and Bellows. Moline Construction of Clare prepared the ground for the project, and Spence Brothers Company of Saginaw installed the buildings during this second phase.

Vetville, as the area of temporary housing came to be known, continued to grow throughout the late 1940s. In summer 1946, Central officials requested the use an empty lot north of the existing housing, which was owned by a Mr. Dunbar. Several private trailers appeared on the lot, and by the time school started in the fall of 1946, 16 private trailers were parked on what came to be known as Dunbar Court. Residents of these trailers, which included at least one family with small children, were given access to the utilities at Vetville by Norvall Bovee. Students living in Vetville also grew as a community. The complex established a council and a constitution a year after it was built. Advertisements in CM Life pointed residents to the Allan-Lockman Grocery in Trailer no. 29, "set up to proved shopping at minimum prices," and GI Joes Famous Sandwiches on the northeast corner of Vetville. In March 1947, 100 Vetville residents (out of 144 total) attended a potluck dinner in the basement of the Methodist church, which featured a game of human bingo and entertainment by Johnny Ryder and his Masters of Corn and Boogie.

Though Vetville thrived in the early postwar era, by the 1950s, the overwhelming influx of veterans and their families had begun to slow. In summer 1952, school officials announced the erection of a new playground on the site of Dunbar Court. The 10 remaining trailers were sold due to a lack of demand and the age of the trailers themselves. The playground would both improve the appearance of the grounds and provide a space for children living nearby. The barracks that had housed single veterans were sold and removed from their location in preparation for construction of what would become Robinson Hall, a new men's dormitory.

The apartments designed as married housing, which came to be called Centralville or Hopkins Court, continued to serve as housing for married students. They had a council and they converted one of the barracks into the headquarters for the council, removing partitions, painting the interior, and draping colorful plastic drapes by the windows. By the beginning of 1953, it was the only barrack left out of the original nine, and it had by this point been converted into a nursery for the children of Centralville residents.

![Vetville [Sheep Sheds II]](/images/default-source/academic-affairs-division/clarke-historical-library/explore-the-collection/explore-online/cmu-history/buildings-on-campus/demolished-buildings/20210921_cmuhistory_existingbuildings_sheesheds002_0038fd33bf9-2bae-42ea-b6de-ce33aedac89c.jpg?Status=Master&sfvrsn=da13ee4c_3) With the opening of the apartments in Preston Court, students living in Centralville moved into new homes and the need for married student housing appeared to be subsiding. In 1957, the school announced plans for an extension to the existing dormitory

on the site and the consequent removal of the reaming sections of the Vetville, including the married student housing project. The College kept some of the remaining 53 buildings on the site for use as storage. These became known as the

"sheepsheds" and remained a fixture on campus for years; one served as the home of the Motor Pool until the mid-1980s. Other buildings were sold to local buyers, and the College advertised them as cottages, garages, hunting cabins, and tool sheds

in an effort to sell them. The College sold one building to the Mt. Pleasant Zonta Club to be used in a school, and another was given to the city to be used as an animal shelter. All of the buildings were either gone or being used for an

alternative purpose within a year. By July 1958, Calkins Hall and Trout Hall were under construction on the site of the Centralville married housing.

With the opening of the apartments in Preston Court, students living in Centralville moved into new homes and the need for married student housing appeared to be subsiding. In 1957, the school announced plans for an extension to the existing dormitory

on the site and the consequent removal of the reaming sections of the Vetville, including the married student housing project. The College kept some of the remaining 53 buildings on the site for use as storage. These became known as the

"sheepsheds" and remained a fixture on campus for years; one served as the home of the Motor Pool until the mid-1980s. Other buildings were sold to local buyers, and the College advertised them as cottages, garages, hunting cabins, and tool sheds

in an effort to sell them. The College sold one building to the Mt. Pleasant Zonta Club to be used in a school, and another was given to the city to be used as an animal shelter. All of the buildings were either gone or being used for an

alternative purpose within a year. By July 1958, Calkins Hall and Trout Hall were under construction on the site of the Centralville married housing.

Home Management House (1949-1974)

Open: 1949 Closed: 1974 Cost: $12,500

In June 1928, Central State Teachers College announced the expansion of its Home Economics program, which would include a home management course that would feature a residency at a local home. The course, which required female students to live in

the practice house for six to eight weeks, utilized a variety of homes near campus for its purposes. For example, President Warriner lent his home to two home economic students while he was away on vacation, and Dean C. C. Barnes' home was

also used at least once. An apartment at 509 S. Fancher and a home at 406 E. Gaylord also provided accommodations for the course. While staying in these homes, the students would practice meal planning and preparation, home care, and budgeting. They

would also use the house to practice social etiquette by hosting tea and dinner parties for various groups around campus.

In June 1928, Central State Teachers College announced the expansion of its Home Economics program, which would include a home management course that would feature a residency at a local home. The course, which required female students to live in

the practice house for six to eight weeks, utilized a variety of homes near campus for its purposes. For example, President Warriner lent his home to two home economic students while he was away on vacation, and Dean C. C. Barnes' home was

also used at least once. An apartment at 509 S. Fancher and a home at 406 E. Gaylord also provided accommodations for the course. While staying in these homes, the students would practice meal planning and preparation, home care, and budgeting. They

would also use the house to practice social etiquette by hosting tea and dinner parties for various groups around campus.

The success of the home management course and the various houses used by faculty and students convinced administrators to invest in a practice house that would be owned by the College. The first such house was located behind the new Arts and Crafts building on Hopkins Avenue. The College appropriated $5,000 for remodeling before the building opened in the fall of 1949 and another $7,500 for additional work in late 1949. Although the house served the department well, a better option became available in under a year. The practice house on Hopkins was sold to Lawrence Durfee and relocated in April 1950.

In the spring of 1950, the College purchased several faculty homes located along the east side of S. Franklin Street in preparation for the construction of the new gymnasium and field house. One of these homes, an innovative split-level home situated in a small copse of woods and originally built in 1940, belonged to Harold J. Powers, chairman of the music department. The house was relocated to the corner of Washington and Preston to be used as the new home economics practice house. Renamed the Home Management House (sometimes called the Home Management Laboratory), it opened for student and faculty use in the spring of 1951. As before, six to eight-week residencies were required for students taking a home management class, and the house remained a central part of the home economics program for almost two decades.

By the late 1960s, home economics departments and courses were changing dramatically and the long-standing tradition of live-in residencies for female students in a home management class was increasingly unpopular and irrelevant to the student body. The University stopped holding live-in courses by the early 1970s. The Home Management House served as classroom space for small discussion groups and office space for six HEFLCE instructors after the home management classes came to an end. In summer 1974, the University announced the future construction of a new art building adjacent to the south end of Wightman Hall and on the site of the Home Management House. Instructors with offices in the house were moved to Sloan and classes were moved to Ronan in preparation for the removal of the building. In October 1974, the garage was moved off campus, and the house itself was removed shortly afterward.

Off Campus Education [Field Services] (1953-1976)

Opened: 1953 Closed: 1976

![Off Campus Education [Field Services]](/images/default-source/academic-affairs-division/clarke-historical-library/explore-the-collection/explore-online/cmu-history/buildings-on-campus/demolished-buildings/20210921_cmuhistory_demobuildings_fieldservices_005642cc2aa-3a22-4891-acec-a3389968ce3e.jpg?Status=Master&sfvrsn=952f9fd5_3) Off-Campus Education, formerly known as Field Services, was originally established in 1926 to provide educational services to non-traditional students in alternative locations. Field Services managed a variety of operations both on and off campus,

including correspondence classes, a speakers' bureau, alumni printing, work with Chambers of Commerce across the state, and even drivers' training for both private drivers and school bus operators. Field Services was originally housed in an office

in Warriner Hall, but the growth of both the College and its services to students after the Second World War made this space increasingly inadequate.

Off-Campus Education, formerly known as Field Services, was originally established in 1926 to provide educational services to non-traditional students in alternative locations. Field Services managed a variety of operations both on and off campus,

including correspondence classes, a speakers' bureau, alumni printing, work with Chambers of Commerce across the state, and even drivers' training for both private drivers and school bus operators. Field Services was originally housed in an office

in Warriner Hall, but the growth of both the College and its services to students after the Second World War made this space increasingly inadequate.

In 1953, Field Services relocated to a new home at 1126 S. Main Street. The building was actually a renovated house that had been recently vacated by the Delta Sigma Phi fraternity, which moved to a new location in Mt. Pleasant. The building was located north of Keeler Union (and north of present-day Ronan Hall, which had yet to be built at the time) and west of Grawn Hall, on the site of a present-day parking lot on the corner of Bellows and Washington. The new location offered more space for Field Services, which remained in this location for over twenty years.

However, by the 1970s, the department had undergone more growth and significant changes. In 1966, the University created the Department of Off-Campus Education, which absorbed Field Services and managed off-campus educational activities from this point forward. In 1975, the University announced plans to relocate Off-Campus Education and several other offices to the recently renovated Rowe Hall. The move allowed Off-Campus Education to move out of the makeshift quarters of the old fraternity house. It also allowed the department to consolidate all of its divisions under a single roof and facilitated work with other departments focused on off-campus activities, such as the Institute for Personal and Career Development. With the old fraternity house at the end of Main Street vacated, the University decided to remove it. The house was razed in the summer of 1976 to help alleviate the parking problem on the north end of campus. Removal of the structure doubled the available spaces in the lot west of Grawn and north of Ronan.

Old Central Hall Physical Training Building (1909-1974)

Opened January 22, 1909 Demolished July 17, 1974 Cost: $50,000

Principal Grawn first expressed the need for a substantial gymnasium facility on campus in 1906 in his report to the State Board of Education. Construction on Central's new gymnasium building began in 1908 on the site of an old frog pond. Designed

by EW Arnold of Battle Creek with the help of the head of the physical education department, the $50,000 building was the fourth structure on campus. It was built on the present-day Warriner Mall and replaced the temporary athletic facilities

in the training school building. The red brick building was over a hundred feet on each side and had two main entrances. It featured locker and dressing rooms, an 18 x 40 ft. swimming pool, a 60 x 33 ½ ft. gymnasium on the southwest corner,

and various offices, examination rooms, and private baths.

Principal Grawn first expressed the need for a substantial gymnasium facility on campus in 1906 in his report to the State Board of Education. Construction on Central's new gymnasium building began in 1908 on the site of an old frog pond. Designed

by EW Arnold of Battle Creek with the help of the head of the physical education department, the $50,000 building was the fourth structure on campus. It was built on the present-day Warriner Mall and replaced the temporary athletic facilities

in the training school building. The red brick building was over a hundred feet on each side and had two main entrances. It featured locker and dressing rooms, an 18 x 40 ft. swimming pool, a 60 x 33 ½ ft. gymnasium on the southwest corner,

and various offices, examination rooms, and private baths.

Construction was complete by the fall of 1909, and Central Hall became the hub of student activities on campus for decades. The building underwent minor changes over its existence. A filter was added to the pool to help chlorinate the water and reduce cleaning and shutdown times. Two new entrances were added to the structure, and a large brick porch on the front of the building was torn down in the 1950s. After the completion of the new student union in 1939 and a new gymnasium in 1951, the building's appearance and shape changed significantly. Homecoming headquarters were in Central Hall for the last time in 1938, and the J-Hop was held there for the last time in 1939. The pool was also removed in the 1950s, the locker rooms were converted into office space, and the old gymnasium was converted into a rifle range. The combination track and balcony overlooking the gym was eventually abandoned. In 1952, lightning struck the flagpole atop Central Hall, leaving only a stub of metal.

While Central Hall saw structural changes, the building itself was used for a variety of purposes and served diverse groups of students throughout its history. During World War I, the building was used for training soldiers and bayonet ranges and trenches were built nearby. At the end of that war, when a flu epidemic broke out among troops on campus, Central Hall became a temporary hospital. In 1921, the inaugural Michigan invitational basketball tournament was held there. During World War II, the building was used to train naval officers in the V-12 and V-5 programs.

ROTC moved into the building in 1952 after the construction of the new gymnasium and field house the previous year. To accommodate the program, the gymnasium on the first floor was converted to a rifle range in 1962. In May 1970, in the

midst of the war in Vietnam and following the US invasion of Cambodia, over thirty students occupied the building and renamed it Freedom Hall. Among their demands was a campus vote over whether to continue the ROTC program, a ban on military

recruitment on campus, and amnesty for all students involved in the occupation of the building. The students remained in the building for five days, during which time they met with President William Boyd about their protest and demands.

ROTC moved into the building in 1952 after the construction of the new gymnasium and field house the previous year. To accommodate the program, the gymnasium on the first floor was converted to a rifle range in 1962. In May 1970, in the

midst of the war in Vietnam and following the US invasion of Cambodia, over thirty students occupied the building and renamed it Freedom Hall. Among their demands was a campus vote over whether to continue the ROTC program, a ban on military

recruitment on campus, and amnesty for all students involved in the occupation of the building. The students remained in the building for five days, during which time they met with President William Boyd about their protest and demands.

As early as the 1940s, college officials and architectural experts began discussing the removal of Central Hall from the campus. With the completion of a new athletic facility and the relocation of ROTC to Finch in the early 1970s, Old Central Hall was left vacated. By 1973, the University was seeking $70,000 to demolish the structure. Funding for the demolition was approved by the state legislature in spring 1974, and demolition began and was completed that summer. The removal of Old Central Hall reshaped the Warriner Mall area, which saw the addition of new sidewalks across the site of the demolished building. Bricks salvaged from the demolition were placed in a circle that served as the hub of the new sidewalks, creating a small park-like area. The Campus Beautification Committee, which was in charge of the project, later installed new benches and some trees on the site.

Old Main [The Normal] (1893-1925)

Opened: 1893 Destroyed by Fire: 1925 Cost: $10,000

Old Main, as it came to be called, was the first building constructed for Central Michigan Normal School. The $10,000 building was designed by Fred Hollister of Saginaw and construction began in 1892. The cornerstone was laid on November 15, 1892,

which contained a document commemorating the establishment of this new school reading:

Old Main, as it came to be called, was the first building constructed for Central Michigan Normal School. The $10,000 building was designed by Fred Hollister of Saginaw and construction began in 1892. The cornerstone was laid on November 15, 1892,

which contained a document commemorating the establishment of this new school reading:

Office of Central Michigan Normal School and Business Institute Mt. Pleasant, Mich. November 15, 1892

The Central Michigan Normal School and Business Institute opened September 13, 1892. Actual attendance on day of opening was thirty-eight of whom four were in the stenography course, ten in the Commercial course and twenty-two in the Normal courses. The actual attendance November 15, 1892 is eighty-nine in all departments.

The building opened in 1893. Significant remodeling was undertaken in 1899 and 1901, when east and west wings were added to the existing structure at a total cost of $61,000.

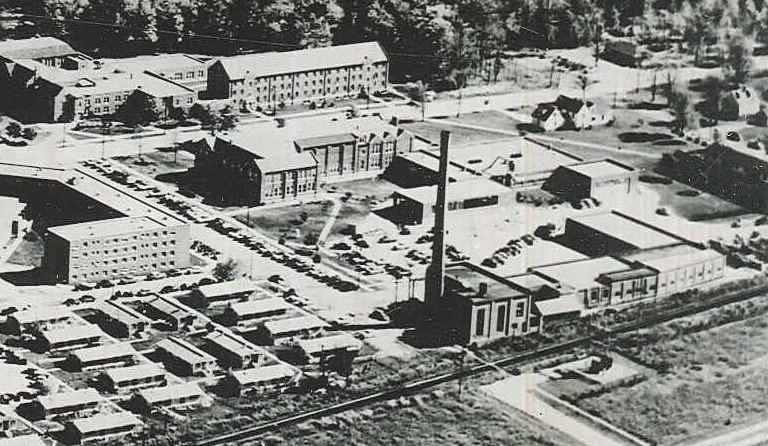

On December 7, 1925, a fire of unknown origin destroyed the building, along with its 30,000 volume library. Anna Barnard, head of the foreign language department, wrote of the fire:

I shall never forget the all-gone feeling I had inside me standing two or three hundred feet from the fiercely blazing structure, I all at once realized that I was looking straight through and seeing the woods beyond.

Surprisingly, the college managed to continue functioning despite the loss of its largest building. The library was relocated to the basement of the dormitory, and over the winter holiday, temporary buildings were constructed on Warriner Mall to house classes. Soon after the fire, special funds were made available by the state to the school and work was begun on a new "administration" building, today's Warriner Hall, which was built on the site of the Old Main.

"Temporary Buildings" [Sheep Sheds I] (1925-1952)

Opened: 1925 Removed from Campus: 1952

![Temporary Buildings [Sheep Sheds I]](/images/default-source/academic-affairs-division/clarke-historical-library/explore-the-collection/explore-online/cmu-history/buildings-on-campus/demolished-buildings/20210921_cmuhistory_demobuildings_tempbuildings_009efe6d6cf-6c35-4cd4-9aa2-148490d613ef.jpg?Status=Master&sfvrsn=98450f4_4) Although the name "sheep sheds" was eventually applied to the post-WWII barracks that were installed to house the swelling numbers of veterans on campus, the original "sheep sheds" were a group of temporary buildings dating from the 1920s. Following

the disastrous 1925 fire that destroyed the old administration building, the Togan-Stiles Company of Grand Rapids constructed three 100-foot structures on the main campus mall, between the site of the administration building and the area where College

Avenue (now University) ended. The buildings, which were constructed in just 16 days, housed the college administration until the completion of the new administration building (now Warriner Hall) in 1928.

Although the name "sheep sheds" was eventually applied to the post-WWII barracks that were installed to house the swelling numbers of veterans on campus, the original "sheep sheds" were a group of temporary buildings dating from the 1920s. Following

the disastrous 1925 fire that destroyed the old administration building, the Togan-Stiles Company of Grand Rapids constructed three 100-foot structures on the main campus mall, between the site of the administration building and the area where College

Avenue (now University) ended. The buildings, which were constructed in just 16 days, housed the college administration until the completion of the new administration building (now Warriner Hall) in 1928.

Although the three buildings were designed to be temporary, they saw a wide variety of uses over the next fifteen years. The buildings served as temporary classrooms and housing throughout the period. After the administration moved into its new headquarters, several proposals for repurposing the vacated building were suggested. These included a kitchenette for the Dormitory Council, parking spaces for the newspaper, and a club house for the Janitors Association. College officials even heard a request from the agriculture department for a new chicken coop. In the end, all three buildings were repurposed for classroom and cafeteria space. One building was relocated at this time to a new site east of the main campus, while the others remained in place.

The remaining two buildings on the main campus continued to serve as temporary space for a wide variety of activities. After a fire at the training school on January 8, 1933, the north temporary building was converted into a manual arts shop, complete with new equipment. Construction crews added cement foundations to support heavy machinery, as well as office and stock rooms. The front part of the renovated building was improved to house the woodworking department, while the rear section was divided into a simulated household, a sheet metal room, and a wood finishing room. An outdoor platform was also added adjacent to the north part of the building for cement work. The south building was also remodeled in 1934 to provide space for a gymnasium for the college elementary school, as well as a rehearsal room for the Appleblossom Club. In 1935, a nursery was added to the north temporary building that could house up to 30 children ages 2 to 5.

Although the temporary buildings served the needs of the College admirably, they were popular targets of scorn among both students and faculty on campus. The buildings, which were considered eyesores, were given the name "sheep sheds" and were often referred to as such in the campus newspaper. To make matters worse, the buildings were located on the main part of campus, blocking the forward view from the new administration building down College Avenue. Students and faculty called for their removal shortly after their construction and continued complaining about the buildings throughout their existence. In the spring of 1937, the College Democrats included the removal of the buildings in their successful election campaign. Their plans were approved by the College administration and the process of removal started immediately.

The College still required the space provided by the buildings, so relocation of the buildings was preferred over removal or demolition. The project would cost an estimated $500, which was raised through donations from faculty, administration, the men's union, and the student council. Students also helped fund the operation by purchasing tickets in support of the removal, which could later be redeemed for a special matinee at the Broadway Theatre. The College hired Lloyd Cole, a local carpenter-contractor, to prepare the buildings for the move, and Nelson Simmons of Mt. Pleasant was in charge of actually moving the buildings.

Relocation of the sheep sheds took place on Commencement Day, June 21, 1937. Each building was first sawed into three separate sections before being moved on a trailer pulled by a tractor. The move was hindered by bad weather and low hanging power lines on Bellows St. Several trees had to be removed from the future locations of the buildings. One of the temporary buildings was placed parallel to the Industrial Arts building, south of the training school and north of the power plant (in the general area of Smith Hall today). The second building was relocated to a small grove across South Franklin from the heating plant (near the northern end of Finch today). One third of the building north of the heating plant was unneeded in the new location and was removed from the structure. It was given to the Appleblossom Club by the College for their campsite at Wixom Lodge near Edenville, where they planned to construct a recreation hall. After the "sheep sheds" had been removed, the campus community had its first unobstructed views from the administration building across the main campus and up College Avenue in over a decade.

In January 1941, the College announced plans to build a new girl's dormitory across the street from the heating plant. This building, which would become the original Ronan Hall, would be constructed on the site of one of the relocated "sheep sheds." Administrators announced that the temporary building would once again be relocated, this time an area west of Alumni Field. Two buildings were moved to the site near Alumni Field, while the third remained on the main part of campus. The temporary buildings served as the home of the campus newspaper, practice space for band members, and a Veterans Administration center.

![Temporary Buildings [Sheep Sheds I] Interior](/images/default-source/academic-affairs-division/clarke-historical-library/explore-the-collection/explore-online/cmu-history/buildings-on-campus/demolished-buildings/20210921_cmuhistory_demobuildings_tempbuildings002_010b3f0e344-44ce-4b10-962d-d2b05db3a0be.jpg?Status=Master&sfvrsn=3157744b_4) Final removal plans were not carried out until 1952, when school officials announced the removal of the temporary buildings from campus. However, they were not simply razed. Two of the three temporary buildings were handed over to the State

Corrections Commission and relocated to a forest in the northern part of the state, where they were used to house prisoners working there. According to a student working for the newspaper at the time, "temporary buildings never die; they just get

moved elsewhere." Although the physical buildings were removed from campus by 1941, the term "sheep sheds" was readily applied to the new temporary structures installed as part of "Vetville" following the end of the Second World War (SEE VETVILLE

SECTION). The last of these sheep sheds, also designed as temporary structures, was not removed from campus until the late 1980s.

Final removal plans were not carried out until 1952, when school officials announced the removal of the temporary buildings from campus. However, they were not simply razed. Two of the three temporary buildings were handed over to the State

Corrections Commission and relocated to a forest in the northern part of the state, where they were used to house prisoners working there. According to a student working for the newspaper at the time, "temporary buildings never die; they just get

moved elsewhere." Although the physical buildings were removed from campus by 1941, the term "sheep sheds" was readily applied to the new temporary structures installed as part of "Vetville" following the end of the Second World War (SEE VETVILLE

SECTION). The last of these sheep sheds, also designed as temporary structures, was not removed from campus until the late 1980s.

Training School (1902-1933)

Opened: August 31, 1902 Destroyed by Fire: January 9, 1933 Cost: $45,000

The original training school was one of the first buildings constructed on campus when it opened on August 31, 1902. It was built at a cost of $45,000. During its existence, it housed the industrial arts department as well as the college elementary

school, where teacher education students worked with the children of Mount Pleasant citizens and Central faculty. However, in 1933, only a few years after the disastrous Old Main fire, the training school was completely destroyed in a blaze that

reportedly started in the paint room. Besides the building itself, over five thousand books disappeared in the fire along with $9,000 in equipment belonging to the industrial arts. Several faculty members lost entire libraries when their

offices were destroyed.

The original training school was one of the first buildings constructed on campus when it opened on August 31, 1902. It was built at a cost of $45,000. During its existence, it housed the industrial arts department as well as the college elementary

school, where teacher education students worked with the children of Mount Pleasant citizens and Central faculty. However, in 1933, only a few years after the disastrous Old Main fire, the training school was completely destroyed in a blaze that

reportedly started in the paint room. Besides the building itself, over five thousand books disappeared in the fire along with $9,000 in equipment belonging to the industrial arts. Several faculty members lost entire libraries when their

offices were destroyed.

Within days, a crew of students and local workers were hired to clean up the site. In total, 36 students and 90 local workmen had the site completely cleared by the end of January 1933, with the exception of an estimated 125,000 bricks that survived the fire. By February 1, the college had announced plans to construct a new training school building on the site of the destroyed structure. The state authorized $75,000 for the construction of the new building, the amount guaranteed by the insurance on the old training school. Construction was underway by late spring. Crews used many of the bricks leftover from the old building in the walls of the new training school. The new building, now known as Smith Hall, opened in May 1934, just over a year since the fire that destroyed the original training school.

Heating Plant I (1905-1948)

Opened: 1905 Closed: 1948

The first heating plant constructed on campus was built in 1905, when school officials authorized the construction a central heating plant located away from the other two main buildings and on the east end of campus, near the present-day location of Smith

Hall. The plant was coal-fired, and Normal boys often helped unload coal from railcars and transport it across campus to the plant.

The first heating plant constructed on campus was built in 1905, when school officials authorized the construction a central heating plant located away from the other two main buildings and on the east end of campus, near the present-day location of Smith

Hall. The plant was coal-fired, and Normal boys often helped unload coal from railcars and transport it across campus to the plant.

In 1932, the Gas Corporation of Michigan converted two of the 150-horsepower steam boilers to natural gas, and the same year an oil-burning boiler was installed. The improvements were part of a large-scale test of the viability of both gas and oil, but by November, officials were convinced natural gas would be the energy source for the school. By December 1932, four of the six boilers had been converted to gas and the other two remained dormant because of the increased efficiency. Workers also laid nearly a mile of pipe from Mission Avenue to the College and added new equipment to the existing gas lines running between the Vernon gas field and Mt. Pleasant. Following the severe winter weather of 1934-35, two oil burning units were installed to help boost the capacity of the heating plant.

The original heating plant supplied steam and heat to all of the buildings on campus through a system of underground tunnels built at the time of the original construction and continually expanded with the addition of new buildings. The tunnels were six feet wide and five feet high, lined with stone, and lighted to facilitate repairs and maintenance. Students "discovered" these pipes again and again over the course of the twentieth century, although exploration of these passageways was discouraged by the University because of safety concerns. Students also had an interesting relationship with the smokestack on the original plant. A heated rivalry developed between freshman and sophomore classes, who would climb the 69-foot stack and plant their initials at the highest point they could achieve, only to be bettered by a member of the competing class shortly afterward.

Improvements and renovations were made to the original heating plant throughout its existence. In 1939, for example, the original smokestack was rebuilt and repaired; the new paint covered the countless initials of the above-mentioned student rivalry. However, the building's age and the growing demands of the campus community limited the long-term usefulness of the facility. By the early 1940s, sections of the building's walls were sagging, leaving rotting timbers exposed. In 1941, with the opening of Sloan Hall, a new girls' dormitory, the needs of campus exceeded the capacity of the original heating plant. In 1941, a State inspector condemned the building, which was finally demolished in 1948 after the completion of a new heating plant on the opposite side of campus.

Bertha Ronan Residence Hall (1923-1970)**

Opened: June 28, 1924

Demolished: August 1970

Cost: $280,000

Capacity: 150

Ronan Hall was the first residence structure at Central Michigan Normal. In addition, it was the first residence hall at a teachers' college in Michigan that was built with funds appropriated by the State legislature. It was located on the southeast corner

of Franklin and Bellows before being demolished in 1970. A plaque can be found near Sloan Hall commemorating the building.

Ronan Hall was the first residence structure at Central Michigan Normal. In addition, it was the first residence hall at a teachers' college in Michigan that was built with funds appropriated by the State legislature. It was located on the southeast corner

of Franklin and Bellows before being demolished in 1970. A plaque can be found near Sloan Hall commemorating the building.

The groundbreaking occurred on October 25, 1922 for a hall that was to be completed by September 1, 1923. Samuel B. Butterworth of Lansing was the architect and the contractor was the Probts, Ford, and Westell Company of Detroit. The craftsmanship of the marble entrance was done by the Christia Batchelder Marble Company. Over 5,700 feet of mahogany was used to frame the windows and doors of this modern building. In addition to being the first residence hall on campus, Ronan had Central's first elevator.

Problems with the foundation delayed the hall's opening by nine months. In August of 1923, one month before the hall was to open, the foundation cracked dangerously. The source of this damage was likely due to poor concrete used in construction and the fact that it was poured when the temperature was below freezing, which did not allow it to cure properly. Rumors of vandalism were rampant, but these were never proven. The damage was quickly repaired with steel rods added to reinforce the original foundation. To reassure students that the building was sound, the contractors undertook dramatic weight tests, showing that the hall's floors could withstand several times the necessary weight.

After the Old Main fire of 1925, the dormitory's recreation room served as a temporary library and the home economics department was housed in the basement. The building's dining hall accommodated 184 people and was used until a new food commons that served the nearby dorms (Ronan, Barnard, and Sloan) opened in 1948. Room rates for the 170-or-so residents ranged from $2 to $4 in the early years of the hall. Although it was not actually named until March of 1939 due to State Board of Education rules prohibiting naming a building for someone currently employed by the institution, the hall was commonly referred to as Ronan Hall from the beginning.

Built as a women's dormitory (there was no men's dorm on campus until Keeler Hall in 1939), the building housed men for the first time in July 1943, when the Navy's V5 program took over the hall for use as a dormitory and training center for new recruits. They stayed for the duration of World War II, turning the hall back over to women in 1945. It again became a men's dorm from 1948 to 1954.

By that time, though, the building was showing its age. Although the residents affectionately referred to it as "Old Bertha," they often complained to the housing authorities about various issues that were not being repaired. In 1966, the Student Senate investigated these allegations and Housing Director Lee Polley blamed the students for most of the damage. Regardless of who was at fault, the contractors hired to look at the building determined that it could not withstand a major renovation due to its structural problems. As a result, the building was razed in August of 1970.

Unlike many public buildings, Ronan did not have a cornerstone (at least, none was found in the rubble). The women of Ronan moved as a group to the newly built Carey Hall in the Towers complex, which was coed by floor.

The hall was named for Bertha M. Ronan, who was a professor in the Department of Physical Education from 1903-1923, and Dean of Women from 1923 until her retirement in 1942. She was given the honor of turning the first shovel of dirt at the groundbreaking

ceremony in 1922 and expressed to the assemblage her hope that the new hall would provide the happiness and inspiration that is found in the atmosphere of a cultured and refined home. She also hoped that it would be a source of pride to alumni and

to those friends of Central Normal who had always been solicitous of its welfare.

The hall was named for Bertha M. Ronan, who was a professor in the Department of Physical Education from 1903-1923, and Dean of Women from 1923 until her retirement in 1942. She was given the honor of turning the first shovel of dirt at the groundbreaking

ceremony in 1922 and expressed to the assemblage her hope that the new hall would provide the happiness and inspiration that is found in the atmosphere of a cultured and refined home. She also hoped that it would be a source of pride to alumni and

to those friends of Central Normal who had always been solicitous of its welfare.

Log Cabin Museum (Alumni Cabin)

Opened: 1929

Closed: 1950

Cost: $750

In the mid-1920s, school officials, led by

President E. C. Warriner, began a drive to establish a log cabin museum

on campus. As planned, a cabin would be built in the woods on campus and

then furnished with relics from Michigan's pioneer past, which were to

be collected from the area. Donations from President Warriner and many

alumni helped finance the project. A summer dramatic reading class

produced the "Log Cabin Plays" as well. Two local cabins were considered

for the project, but officials eventually paid $250 for a cabin located

five miles west of Mt. Pleasant on land owned by Charles McCarthy. The

cabin was originally built in 1878 out of locally harvested pine and was

disassembled and catalogued in preparation for the move to campus.

In the mid-1920s, school officials, led by

President E. C. Warriner, began a drive to establish a log cabin museum

on campus. As planned, a cabin would be built in the woods on campus and

then furnished with relics from Michigan's pioneer past, which were to

be collected from the area. Donations from President Warriner and many

alumni helped finance the project. A summer dramatic reading class

produced the "Log Cabin Plays" as well. Two local cabins were considered

for the project, but officials eventually paid $250 for a cabin located

five miles west of Mt. Pleasant on land owned by Charles McCarthy. The

cabin was originally built in 1878 out of locally harvested pine and was

disassembled and catalogued in preparation for the move to campus.

Relocation of the cabin cost a total of about $500, which included repairs and minor decorating to the cabin. In addition, a stone foundation had to be laid in the woods east of main campus, which were called Normal Woods or Alumni Woods (located in the area of Finch Fieldhouse today). A fireplace for the cabin also had to be built. The cabin was constructed on the freshly-laid foundation in November 1928, and students helped fill the spaces between the logs and shingle the roof. Construction and repairs were complete by the spring. In June 1929, the building was officially presented to the State Board of Education and was featured in commencement ceremonies that month. The building remained in this location on campus for the next 21 years.

Although the log cabin was brought to campus as a planned museum, locating and maintaining a worthwhile collection proved difficult. After several pleas, both general and specific, from President Warriner and others for donations of materials and relics from the pioneer era, several students and local residents did indeed donate interesting artifacts that would have served well in such a museum, including a musket, powder horn, and rocking cradle. The cabin did receive some care from a third grade class at the training school. As part of their study on pioneer life, the class crafted curtains, benches, candles, and a four-poster bed for the cabin.

However, the collection of artifacts never grew to become large enough to fill the museum, and the log cabin remained unused in any official capacity for the first few years of its existence. By the early 1930s, however, the campus community began looking to new uses for the structure, which was now commonly called Alumni Cabin or just the "log cabin." Informal parties were sometimes held in the cabin and Bertha Ronan led the change to make the log cabin a general meeting place for students, alumni groups, and local scout organizations. In 1933, Central received nearly $2,000 and manpower from the Civil Works Administration for improvements to the cabin. The fireplace was repaired, the second story was braced, and a kitchen was added to facilitate meetings.

The cabin remained a popular meeting spot for students throughout the 1930s, hosting dinners and small gatherings of various sorts. When Keeler Union (now Powers Hall) opened in 1939, however, the cabin was once again abandoned. It remained in its location in Alumni Woods until construction on the new Health and Physical Education Building (Finch Fieldhouse) began. At this point, the cabin was once again dismantled, catalogued, and stored. In March 1950, the cabin was donated to the Isabella County division of the Saginaw Valley Trails Council of the Boy Scouts. They rebuilt the structure on land donated by the Weidman Estate on the Chippewa River, where it would be used for camping and field trips.

The collection of artifacts

housed in the cabin for a time was catalogued and, along with a

collection of bird specimens held in the biology department, relocated

to a new museum on campus in the former quarters of the Clarke

Historical Library in Ronan Hall, which had been vacated with the

completion of the new Park Library. This collection was used to create

the what has become the Museum of Cultural and Natural History, which is

housed in Rowe Hall today.

Barnard Hall (1948-1996)

Opened: September 23, 1948 Demolished: 1997 Cost: $1.4 million Capacity: 400

The Anna M. Barnard Residence Hall was the fourth residence hall built on the campus of CMU. It was the first designed by architect Roger Allen of Grand Rapids, who later designed many residence and academic halls across campus. The $1.4 million

building, designed to house 400 students when it opened, was built by the Weber Construction Company of Bay City over the course of 1947 and 1948. It was constructed with the latest fireproofing techniques: gypsum block partitions, steel casements,

and steel stairways. At the time it was built, Barnard was the largest residence hall on campus. It officially opened on September 23, 1948.

The Anna M. Barnard Residence Hall was the fourth residence hall built on the campus of CMU. It was the first designed by architect Roger Allen of Grand Rapids, who later designed many residence and academic halls across campus. The $1.4 million

building, designed to house 400 students when it opened, was built by the Weber Construction Company of Bay City over the course of 1947 and 1948. It was constructed with the latest fireproofing techniques: gypsum block partitions, steel casements,

and steel stairways. At the time it was built, Barnard was the largest residence hall on campus. It officially opened on September 23, 1948.

Like many halls, Barnard opened before it was actually completed. When the first residents moved in, there were no beds and the lobby was not yet finished. Nevertheless, the demand for housing after World War II led to the building's early opening and for it to be filled beyond capacity for several years thereafter. The building was built as a women's residence hall and housed women from its opening until 1964, when it was converted to a men's hall. With the completion of the southeast quad in 1966, women again moved into Barnard. The building continued to be a women-only hall until 1973-74, when it became coed until it closed.

Designs also called for an adjoining food commons that seated 600 and served Barnard, Sloan, and Ronan residence halls. This type of quadrangle arrangement was among the first of its kind and became a model for other residence hall complexes on campus. Room and board was set at $207.25 per semester for all three halls. The students of Barnard published a hall newspaper for several years starting in 1953. A high point in the history of Barnard Hall occurred in 1955, when former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited Central and stayed in the hall's guest room.

Barnard Hall continued to serve the needs of on-campus students for decades. However, in 1993 Barnard and Tate residence halls were closed due to low enrollment, structural problems, and general inefficiency. The Board of Trustees announced future plans to demolish Barnard and Tate Halls in December 1995. The decision to raze them was based on the high cost of remodeling and continued low student enrollment. The University awarded the demolition contract to Diamond Dismantling, a Detroit company, who agreed to complete the demolition for $357,221. Demolition began in May 1996, after furniture was auctioned and utility equipment was salvaged. Certified Abatement of Detroit and Termico Incorporated of Midland were hired to assist with the removal of asbestos from the site. Demolition was complete within a few months and a parking lot was laid on the spot of Barnard and Tate Halls in 1997.

In December 2011, the CMU Board of Trustees announced plans for a new Graduate Student Housing Project on the site of the former Barnard and Tate Halls. The Christman Company of Lansing was hired to contract out the work. The total budget for the project

was $28.5 million, which included funds for the expansion of an adjacent parking lot. The new buildings were closely modeled on the architecture of Barnard Hall, both to recall the dormitory that once stood on the location and also to better

incorporate the new buildings into the existing architectural style on north campus. The new graduate housing, which opened in 2013, was built to serve the recently completed College of Medicine.

In December 2011, the CMU Board of Trustees announced plans for a new Graduate Student Housing Project on the site of the former Barnard and Tate Halls. The Christman Company of Lansing was hired to contract out the work. The total budget for the project

was $28.5 million, which included funds for the expansion of an adjacent parking lot. The new buildings were closely modeled on the architecture of Barnard Hall, both to recall the dormitory that once stood on the location and also to better

incorporate the new buildings into the existing architectural style on north campus. The new graduate housing, which opened in 2013, was built to serve the recently completed College of Medicine.

Barnard Hall was named for the head of the Department of Foreign Languages from 1899-1944. She resigned October 1, 1944. An article in the July 30, 1947 edition of CM Life reported some of her accomplishments:

In the many years Miss Barnard taught here she has made countless friends among the alumni of the school and has been a considerable influence upon the lives of students as well as upon the institution itself. She has been a keen student of languages throughout her teaching career, spending every opportunity in travel abroad to get firsthand information. Among the countries in which she has lived and studied are England, France, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Greece, the Near East, Denmark and Scandinavian Countries.

Tate Hall (1956-1996)

Opened: September 1956

Demolished: 1997

Cost: $1.14 million

Capacity: 300

The Rachel Tate Residence Hall was built, along with several other residence halls, to meet the needs of a rapidly expanding campus

population in the 1950s. The $1.14 million building was designed by Roger Allen and Associates of Grand Rapids, who designed many other residential and academic buildings on Central's campus. Tate shared a food commons built in 1948 as part of Barnard

Hall.

The Rachel Tate Residence Hall was built, along with several other residence halls, to meet the needs of a rapidly expanding campus

population in the 1950s. The $1.14 million building was designed by Roger Allen and Associates of Grand Rapids, who designed many other residential and academic buildings on Central's campus. Tate shared a food commons built in 1948 as part of Barnard

Hall.

The designs for Tate Hall saw the last change in room layout until the building of the Towers complex in the late 1960s. The building copied the innovative suite plan designed for Robinson Hall, but added a second bedroom to the plan. This plan was used on the next eleven residence halls at Central Michigan University. Construction was underway by early 1956, and the cornerstone was laid in July 1956. The building was opened a few short months later in September, but it was not dedicated until January 19, 1958. Although its 75 suites were designed to house 300 students, the first year of operation saw 325 women rooming there. It was located next to the President's House, now Carlin Alumni House, on the present-day location of parking lot 8.

Its location next to the president's residence, led to many dinner invitations to the president and his wife as apologies for excess noise. In 1958, the entire Homecoming court lived in Tate Hall. The building housed women from 1956 to 1972, and

became coed for the rest of its history.

Its location next to the president's residence, led to many dinner invitations to the president and his wife as apologies for excess noise. In 1958, the entire Homecoming court lived in Tate Hall. The building housed women from 1956 to 1972, and

became coed for the rest of its history.

Tate Hall continued to serve the needs of on-campus students for decades. However, in 1993 Tate and Barnard residence halls were closed due to low enrollment, structural problems, and general inefficiency. The Board of Trustees announced future plans to demolish Barnard and Tate Halls in December 1995. The decision to raze them was based on the high cost of remodeling and continued low student enrollment. The University awarded the demolition contract to Diamond Dismantling, a Detroit company, who agreed to complete the demolition for $357,221. Demolition began in May 1996 after furniture was auctioned and utility equipment was salvaged. Certified Abatement of Detroit and Termico Incorporated of Midland were hired to assist with the removal of asbestos from the site. Demolition was complete within a few months and a parking lot was laid on the spot of Barnard and Tate Halls in 1997.

In December 2011, the CMU Board of Trustees announced plans for a new Graduate Student Housing Project on the site of the former Barnard and Tate Halls. The Christman Company of Lansing was hired to contract out the work. The total budget for the project was $28.5 million, which included funds for the expansion of an adjacent parking lot. The new residence halls were closely modeled on the architecture of Barnard Hall, both to recall the building that once stood on the location and also to better incorporate the new buildings into the existing architectural style at the north end of campus. The new graduate housing, which opened in 2013, was built to serve the recently completed College of Medicine.

The building was named for Rachel Tate, who was an instructor in the Department of English and a part-time women's dean from 1897 to 1916. She was born October 12, 1848 in Berrien County, Michigan. She attended Niles High School, then earned her degree

from Michigan State Normal (now Eastern Michigan) in 1889. She did graduate work at Harvard and the University of Chicago. Before coming to Central, she taught grade school in Chicago, was commissioner of schools in Berrien County, and taught at Benton

Harbor College and St. Mary's College in Illinois. She died on March 16, 1916. In her memory, the Rachel Tate Literary Society was formed in 1924, at a time when fraternities and sororities were banned at Central. In 1940, the "literary society"

was reorganized as Sigma Phi Delta sorority, then as Alpha Sigma Alpha in 1941.

The building was named for Rachel Tate, who was an instructor in the Department of English and a part-time women's dean from 1897 to 1916. She was born October 12, 1848 in Berrien County, Michigan. She attended Niles High School, then earned her degree

from Michigan State Normal (now Eastern Michigan) in 1889. She did graduate work at Harvard and the University of Chicago. Before coming to Central, she taught grade school in Chicago, was commissioner of schools in Berrien County, and taught at Benton

Harbor College and St. Mary's College in Illinois. She died on March 16, 1916. In her memory, the Rachel Tate Literary Society was formed in 1924, at a time when fraternities and sororities were banned at Central. In 1940, the "literary society"

was reorganized as Sigma Phi Delta sorority, then as Alpha Sigma Alpha in 1941.

Alumni Field (1930-1997)

Opened: 1930 Closed: 1997 Cost: $40,000

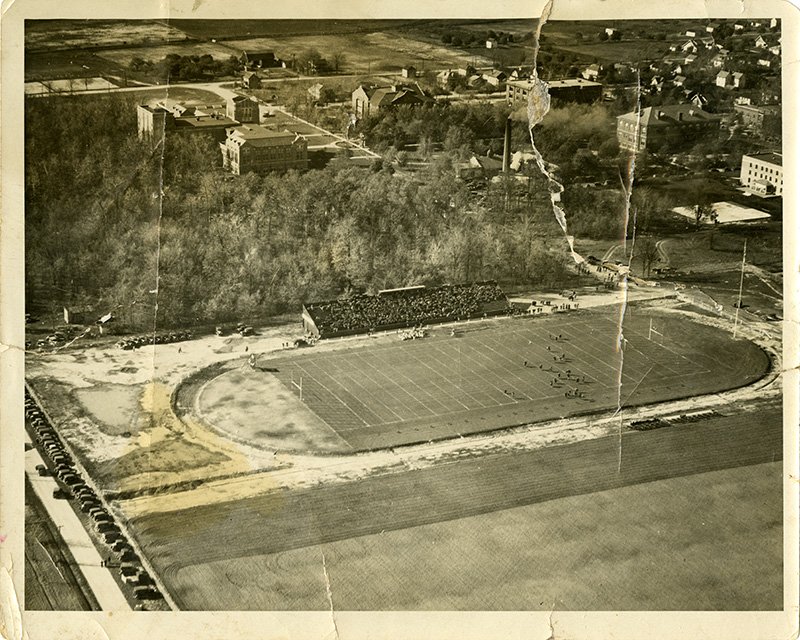

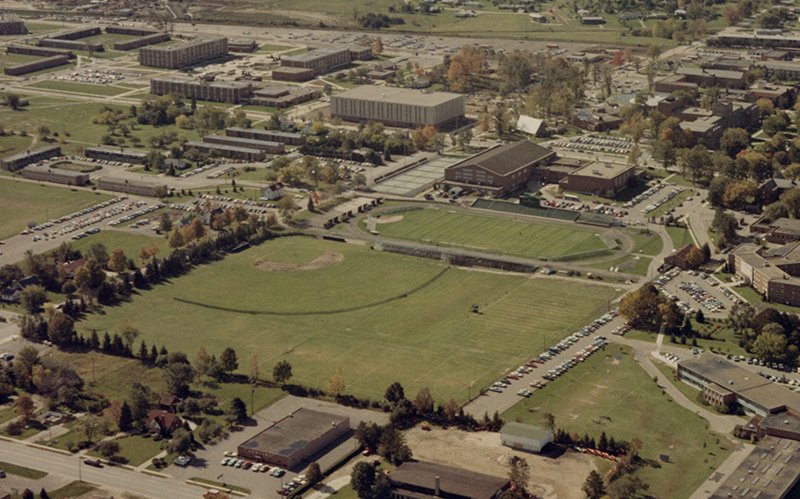

Alumni Field and the adjacent University Baseball Stadium (also known as Alumni Stadium) were located on a 22 acre plot of land in the heart of Central Michigan University's campus. Major improvements to the field were made in 1930, when a new field house

was constructed and a new Alumni Field was established. Alumni Field contained a track and field facility, a gridiron, a grandstand capable of seating 2,500 spectators, a baseball diamond, and practice fields. The complex was well fenced, properly

drained, and of sufficient size for future plans for expansion. Its location in the center of campus made it a convenient and popular place for students to attend athletic events or to stop by on their way to and from classes.

Alumni Field and the adjacent University Baseball Stadium (also known as Alumni Stadium) were located on a 22 acre plot of land in the heart of Central Michigan University's campus. Major improvements to the field were made in 1930, when a new field house

was constructed and a new Alumni Field was established. Alumni Field contained a track and field facility, a gridiron, a grandstand capable of seating 2,500 spectators, a baseball diamond, and practice fields. The complex was well fenced, properly

drained, and of sufficient size for future plans for expansion. Its location in the center of campus made it a convenient and popular place for students to attend athletic events or to stop by on their way to and from classes.

Alumni Field underwent significant renovations during its forty-plus year run as the home of CMU athletics. In 1938, lights were installed on the football field, allowing for night games. In 1941, with the help of the Public Works Administration, tennis courts were added to the athletic field. The baseball scoreboard was replaced in 1970 and again in 1990. In 1981, Central Michigan University paid $350,000 to substantially renovate Alumni Field, installing bleacher-type seating, a ticket booth, concession stand, and restroom and media facilities.

In 1986, the track and field facility that was commonly known as Alumni Field (although the name also applied to the general athletic grounds of which the track was only a part) was officially renamed the Lyle Bennett Track, in honor of a former CMU track

coach. A year later, the baseball stadium (commonly known as Alumni Stadium or just the baseball stadium) was rededicated as Theunissen Stadium in honor of Bill Theunissen, a former CMU baseball coach, athletic director, and Dean of Health, Physical

Education, and Recreation.

In 1986, the track and field facility that was commonly known as Alumni Field (although the name also applied to the general athletic grounds of which the track was only a part) was officially renamed the Lyle Bennett Track, in honor of a former CMU track

coach. A year later, the baseball stadium (commonly known as Alumni Stadium or just the baseball stadium) was rededicated as Theunissen Stadium in honor of Bill Theunissen, a former CMU baseball coach, athletic director, and Dean of Health, Physical

Education, and Recreation.

Although it had been home to many athletic events since 1930 and the home of CMU baseball since 1949, Alumni Field no longer exists in physical form. On November 4, 1972, the football team played its first game at the new Perry Shorts Stadium. By the 1990s, the University made an effort to concentrate all of the athletic facilities on the south end of campus. Following the construction of the new Theunissen Stadium, the Indoor Athletic Center, and new track and field facilities, University officials announced plans for a new instructional facility on the site of the old Alumni Field. The Health Professions Building and the College of Medicine are now situated where Alumni Field athletic complex once existed and the grassy area between these facilities and Finch Field house is the former site of the football field and Bennett Track.

Old Theunissen Stadium (1949-2001)

Opened: 1949 Closed: 2001

Central Michigan University's baseball team played at the facilities that would eventually become the original Theunissen Stadium starting in 1949. The University Baseball Stadium (informally known as Alumni Stadium) was built on the corner of Preston

and East Campus Drive and was part of a larger collection of outdoor athletic facilities known as Alumni Field. The stadium hosted games from 1949 until 2001. Located in the heart of CMU's campus, baseball games could be heard from classroom windows

and were often attended by students on their ways to and from class.

Central Michigan University's baseball team played at the facilities that would eventually become the original Theunissen Stadium starting in 1949. The University Baseball Stadium (informally known as Alumni Stadium) was built on the corner of Preston

and East Campus Drive and was part of a larger collection of outdoor athletic facilities known as Alumni Field. The stadium hosted games from 1949 until 2001. Located in the heart of CMU's campus, baseball games could be heard from classroom windows

and were often attended by students on their ways to and from class.

Alumni Stadium was rededicated in 1987 as the William V. Theunissen Stadium. It was named after Bill Theunissen, a former baseball coach with the University who led the team to a 151-114-1 record during his tenure in the 1950s and early 1960s. At the time of his retirement in 1986, Theunissen was the winningest coach in CMU baseball history, and he currently ranks fourth on that list. Besides playing a variety of sports and coaching baseball at CMU, Theunissen became a professor of health and physical education before serving as dean of the School of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation (later renamed the School of Education, Health, and Human Services).

The stadium was improved a number of times during its tenure as home of CMU baseball. The University built a new scoreboard in 1970, replacing it with a more modern one again in 1990. The stadium underwent a significant renovation in 1980-81, when the University spent $350,000 for improvements including the installation of bleacher-style seating, a ticket booth, concession stands, and restroom and media facilities.

In 2002, the new Theunissen Stadium opened on West Campus Drive as part of an effort to concentrate all of the University's athletic facilities on the south end of campus. At the closing ceremony for the old stadium, Bill Theunissen joined over a hundred former players to bid farewell. The old Theunissen Stadium, which hosted its last season in 2001, was demolished to make room for the Health Professions Building and the College of Medicine, which occupy the site today.

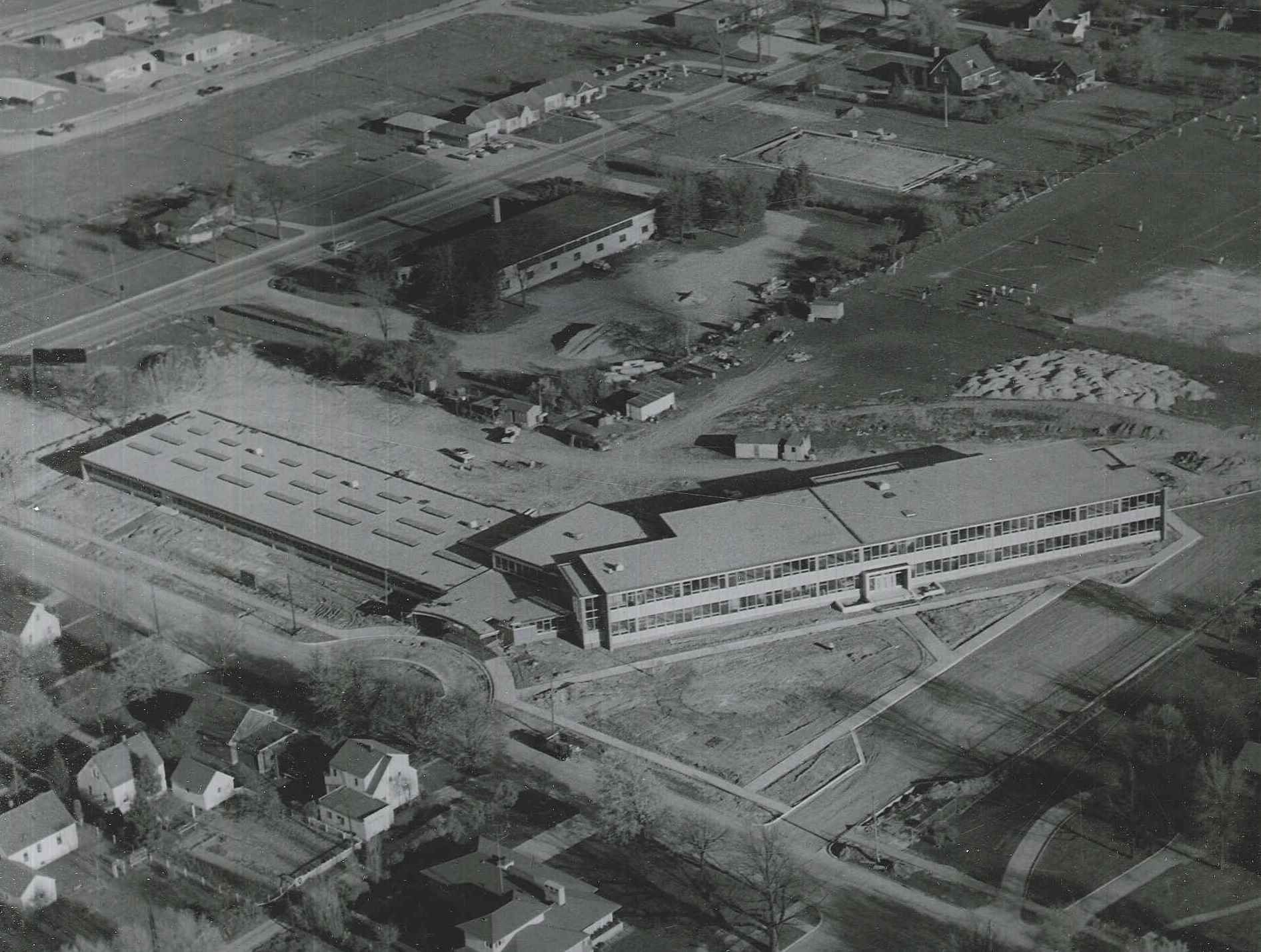

Rowe Hall East Wing (1958-1998)

Opened: 1958 Closed: 1998 Cost: $1 Million

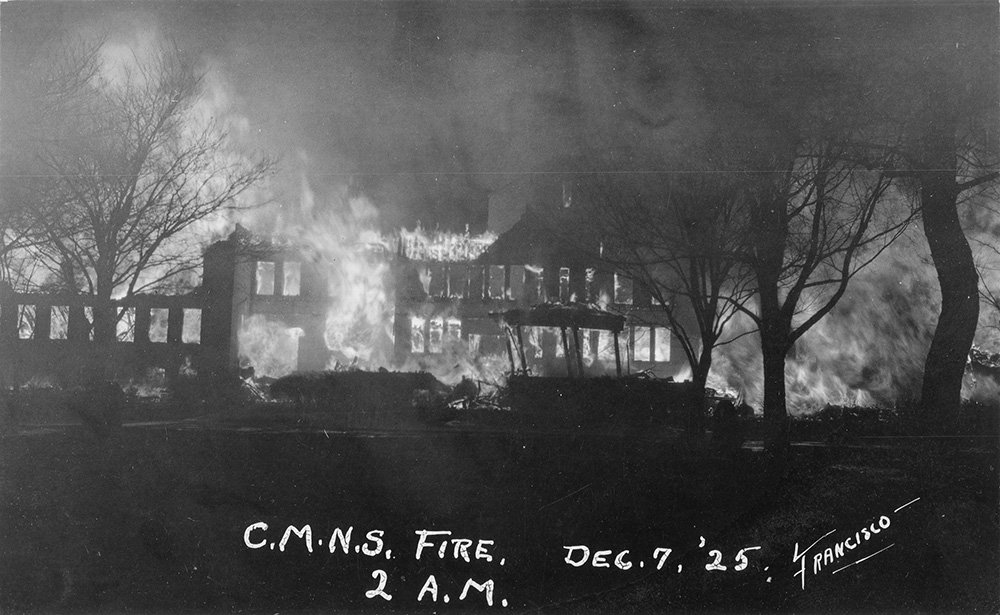

College officials announced plans for a new college elementary, psychology, and education building in 1956. Groundbreaking on the $1 million building, designed by architect Roger Allen, took place in May 1957. In December 1957, President Anpsach announced

the new building would be named in honor of Eugene C. Rowe, and in May 1958, the cornerstone was laid. The cornerstone contained signatures of all the elementary students attending the school in 1958, as well as a photograph. The building was designed

with flexibility in mind, featuring movable dividers between classrooms and movable cupboards and storage within classrooms.

College officials announced plans for a new college elementary, psychology, and education building in 1956. Groundbreaking on the $1 million building, designed by architect Roger Allen, took place in May 1957. In December 1957, President Anpsach announced

the new building would be named in honor of Eugene C. Rowe, and in May 1958, the cornerstone was laid. The cornerstone contained signatures of all the elementary students attending the school in 1958, as well as a photograph. The building was designed

with flexibility in mind, featuring movable dividers between classrooms and movable cupboards and storage within classrooms.

The building was opened in the fall of 1958 and saw some significant renovations over the next few decades, including a renovation of the office wing in 1969 and the addition of an elevator in the 1980s. The former gymnasium now houses the Center for Cultural and Natural History, which relocated to Rowe Hall from Ronan Hall in 1975. The Museum reopened to the public in April 1978. A Native American art gallery, started by a donation from Olga and G. Roland Denison, was dedicated in 1994.

In June 1998, a fire broke out and significantly damaged the east wing of Rowe Hall. This wing had until this point housed the College of Extended Learning (CEL), and the fire left many faculty members without office space. In addition to the loss of CEL space and materials, other offices were left covered in soot and the Museum of Cultural and Natural History also sustained smoke damage. The Museum remained closed until September, and temporary facilities for the departments displaced by the fire were set up in the Student Activity Center, Warriner Hall, Powers Hall, Park Library, and Woldt Hall. Cost of the clean-up and post-fire renovations reached $400,000. The 16,500 square foot east wing was determined to be too heavily damaged and was razed. A new entrance was built on the east side of the building, new brick facing was added to the section of the building adjacent to the demolition, and sidewalk and landscaping improvements helped integrate the renovated building into the exiting surroundings.

The building was named after the founder of the Department of Psychology and Education at Central. Eugene C. Rowe was born in Monroe, Michigan, on March 8, 1870. He received his AB from Olivet in 1897 and his PhD from Clark University in 1909. He came to Central in 1902 and retired in 1936. He was the first faculty member at Central to have a PhD.

Rowe was a prominent psychologist. He offered the first Mental and Sex Hygiene courses in the state. He was a clinical psychologist for the New York City Police from 1915 to 1916. During World War I, he was the US Army's Chief Psychological Examiner,

attaining the rank of Major. He helped design the Army Alpha test, which is a fore-runner of the modern IQ tests. He was a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and a life member of the American Psychological Association.

In addition to his work as a psychologist, Rowe was also a pioneer in the controversial eugenics movement. He died on December 31, 1946.

Rowe was a prominent psychologist. He offered the first Mental and Sex Hygiene courses in the state. He was a clinical psychologist for the New York City Police from 1915 to 1916. During World War I, he was the US Army's Chief Psychological Examiner,

attaining the rank of Major. He helped design the Army Alpha test, which is a fore-runner of the modern IQ tests. He was a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and a life member of the American Psychological Association.

In addition to his work as a psychologist, Rowe was also a pioneer in the controversial eugenics movement. He died on December 31, 1946.

Football Office (circa 1960's-1974)

Opened: circa 1960's Closed: 1974

The head football coach and his staff shared office space with the rest of the athletic department since the establishment of the program in the early-twentieth century. By the 1960s, coach Bill Kelly's office in Finch Fieldhouse was growing increasingly

inadequate to meet the football program's needs. In the late 1960s, the football coach and his office staff moved to a long-standing building on Preston near the intersection with Franklin, which became known as the Football Office.

The head football coach and his staff shared office space with the rest of the athletic department since the establishment of the program in the early-twentieth century. By the 1960s, coach Bill Kelly's office in Finch Fieldhouse was growing increasingly

inadequate to meet the football program's needs. In the late 1960s, the football coach and his office staff moved to a long-standing building on Preston near the intersection with Franklin, which became known as the Football Office.

In 1974, following the completion of the Rose Center and relocation of athletic activities and offices to the south end of campus, the University decided to redevelop the area on which the football office was situated (between Park Library and Foust Hall today). The building was sold to Robert Sweet in April 1974 for $4,392 and was removed on May 1, 1974. After removal, the House brothers of Rosebush agreed to restore and landscape the area at a cost of $4,000, which they completed summer 1974.

President Emeritus House [Anspach's Home] (1959-circa 1970s)

Opened: 1959 Closed: circa 1970's

When President Anspach retired in 1959, he moved into a house located at 3582 Fancher. The house was situated within the Preston Court Apartment complex, near the site of the present-day music building. The house enabled Anspach and his wife to reside

on campus even after his retirement. After moving in during the summer of 1959, the Anspachs lived in the house for a number of years. However, at some point during the 1970s the house was removed from campus.

When President Anspach retired in 1959, he moved into a house located at 3582 Fancher. The house was situated within the Preston Court Apartment complex, near the site of the present-day music building. The house enabled Anspach and his wife to reside