Homecoming

An Enduring Campus Tradition

Homecoming is the quintessential campus event. Since 1924, when Central celebrated its first Homecoming, thousands of alumni have returned to campus for a weekend celebration that allows them to renew ties with old friends, revisit past haunts, see what's new on campus, and, of course, cheer on the team.

We invite you to revisit Central Michigan University's past Homecomings by clicking on any of the headings below. If you are interested in learning more details about CMU's past Homecoming celebrations please also read an article about the event in

the Clarke Historical Library's fall 2000 newsletter.

This exhibit was prepared by the staff of the Clarke Historical Library as part of Central Michigan University's 2000 Homecoming celebration. Special Thanks to Mr. Hudson Keenan who made available to us the color image of the 1952 queen's float.

CMU's First Homecoming

A student, Bourke "Dutch" Lodwyk, brought the idea of Homecoming to Mount Pleasant. In the fall of 1924 Dutch was sent on a trip to Albion College to scout the school's football team prior to its game with Central. He came back with the

goods on the team and also with tremendous enthusiasm to establish here what he had witnessed in Albion: a fall Homecoming. The idea took some selling because of various practical problems. For example, some people worried about who

would pay for the postage to mail invitations to the event to alumni. Despite these concerns, students, faculty, and the administration eventually embraced the idea.

A student, Bourke "Dutch" Lodwyk, brought the idea of Homecoming to Mount Pleasant. In the fall of 1924 Dutch was sent on a trip to Albion College to scout the school's football team prior to its game with Central. He came back with the

goods on the team and also with tremendous enthusiasm to establish here what he had witnessed in Albion: a fall Homecoming. The idea took some selling because of various practical problems. For example, some people worried about who

would pay for the postage to mail invitations to the event to alumni. Despite these concerns, students, faculty, and the administration eventually embraced the idea.

Central held its first Homecoming on Saturday, November 22, 1924. The celebration actually began on Friday with a pep rally and a bonfire. A dance, the largest of the season, followed. It continued until 11:45 p.m., when the band played "Taps." The next morning the American Legion decorated the town with flags, and a parade of approximately one hundred cars drove down Main Street. That afternoon fortune smiled on the football team, and Central defeated Alma College 13-0. The day ended with various parties and a "rush" at the Broadway Theater. "Rushing" was a student tradition, frowned on by the administration, in which people rushed past the ticket takers to enjoy a free evening's entertainment.

Pre-World War II

Central's pre-World War II Homecomings were composed of events built upon ties to school friends and emotions felt by the alumni about their years at Central. Homecoming continued and grew because it created a way for old college friends

to come together, allowed students to show their support for the school while meeting with alumni, and gave the faculty and administration the opportunity to put the school's best face forward.

Central's pre-World War II Homecomings were composed of events built upon ties to school friends and emotions felt by the alumni about their years at Central. Homecoming continued and grew because it created a way for old college friends

to come together, allowed students to show their support for the school while meeting with alumni, and gave the faculty and administration the opportunity to put the school's best face forward.

Then as now, the parade, the band, and the game were key elements in the celebration. However, in the early years Homecoming was much smaller than it is today. At its peak, only about 3,000 students and alumni attended. In 1925 the

first floats appeared in the Homecoming parade, and prizes were awarded for the best float. But the parade had no unifying theme. Early floats were often merely a decorated car or a small trailer that had been dressed up for the

event. Perhaps because the number of people on hand was small, the parade was broadly inclusive. On occasion the entire student body would march in it. Houses, particularly those in which students lived, and later the dormitories,

were also decorated for the event.

All-school dances played an important part in the early years of the celebration. Frequently dances were held on both Friday and Saturday evenings. Student rushes on the Broadway, and later the Ward, Theaters also occurred regularly.

Particular groups took on specific duties. For example, freshmen would scour the city for days to gather together the "flammables" to be lit as the climax of Friday night's pep rally.

Some innovations of the prewar years have become honored traditions. Of particular note is the CMU Fight Song, which was composed by student Howard "Howdy" Loomis and played for the first time at the 1934 Homecoming. Other innovations

had less of an impact. In 1929 the workers in the college's plant department constructed a huge electrical sign that flashed "Central" and hoisted it to the top of the Administration Building (today Warriner Hall) tower. The sign,

however, soon disappeared. The decision in 1930 to have President Warriner make the game's opening kick (a twenty-yard kickoff, described as "beautiful" in the yearbook) was never repeated.

Some innovations of the prewar years have become honored traditions. Of particular note is the CMU Fight Song, which was composed by student Howard "Howdy" Loomis and played for the first time at the 1934 Homecoming. Other innovations

had less of an impact. In 1929 the workers in the college's plant department constructed a huge electrical sign that flashed "Central" and hoisted it to the top of the Administration Building (today Warriner Hall) tower. The sign,

however, soon disappeared. The decision in 1930 to have President Warriner make the game's opening kick (a twenty-yard kickoff, described as "beautiful" in the yearbook) was never repeated.

With the coming of the Second World War limitations on rail travel and the rationing of critical supplies such as gasoline made it difficult or impossible for alumni to return to campus. Consequently, Homecoming was not held between 1943 and 1945.

Classic Era

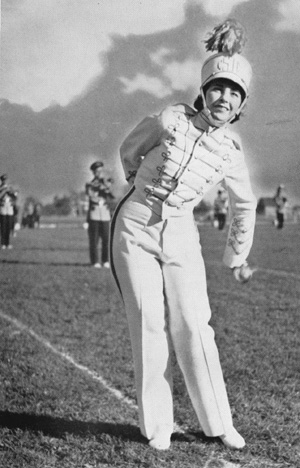

With the end of World War II, Homecoming was reborn in 1946 and entered its "classic" era. Homecoming became one of the most important events on the student calendar and was also well attended by the alumni. It was celebrated with ever

increasing enthusiasm and extravagance.

With the end of World War II, Homecoming was reborn in 1946 and entered its "classic" era. Homecoming became one of the most important events on the student calendar and was also well attended by the alumni. It was celebrated with ever

increasing enthusiasm and extravagance.

The 1946 Homecoming celebration featured a parade with twenty-two floats. Two all-school dances, one a ballroom dance and the other a square dance, followed the traditional Friday night pep rally and bonfire. Capitalizing on the new team

name adopted in 1941, "Chippewas," "Indian pageantry" was added to the event. The 1946 Homecoming also marked the election of the first Homecoming queen.

In the 1950s Homecoming grew ever larger. Floats became more elaborate. The election of a queen involved increasingly complex activities. Over time the supporters of various candidates for queen paid for ads in the campus newspaper, mounted

loudspeakers on cars to turn out the vote, and even "bombed" the campus with fliers thrown from an airplane. By the late 1950s the post game formal dance had become so popular that all who wanted to attend could not be housed under

a single roof. Thus two balls were held. One was held in Finch Fieldhouse. A second ball was housed in Keeler Union and later, after Keeler was closed, in the University Center.

In the 1950s Homecoming grew ever larger. Floats became more elaborate. The election of a queen involved increasingly complex activities. Over time the supporters of various candidates for queen paid for ads in the campus newspaper, mounted

loudspeakers on cars to turn out the vote, and even "bombed" the campus with fliers thrown from an airplane. By the late 1950s the post game formal dance had become so popular that all who wanted to attend could not be housed under

a single roof. Thus two balls were held. One was held in Finch Fieldhouse. A second ball was housed in Keeler Union and later, after Keeler was closed, in the University Center.

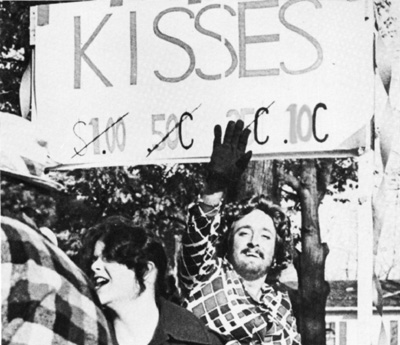

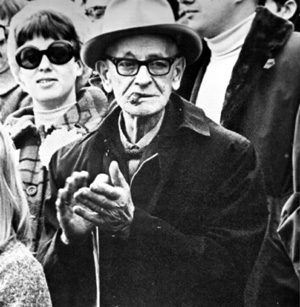

Although far more complex than in the pre-war years, Homecoming still retained the touch of the irreverence found in the pre-war rushes and class hijinks. Most representative of this aspect of Homecoming during the classic period was Elvira

Scratch. One of the events longest running gags, Elvira was the Veterans' Club never very serious candidate for queen. Between 1952 and 1981 Elvira changed her appearance annually but always bore a marked resemblance to one of the

club's more extroverted members in women's clothing. She shaved neither her beard nor her legs, disdained showers, wore a tasteless dress, and was frequently seen with a beer in hand. Her float in the parade was often outlandish. One

year she rode a manure spreader while another year she sat atop a toilet. Beside from her parade floats, she is also remembered for her annual effort to dash onto the football field at half-time to kiss the most senior member of Central's

administration unlucky enough to come within her reach.

Although far more complex than in the pre-war years, Homecoming still retained the touch of the irreverence found in the pre-war rushes and class hijinks. Most representative of this aspect of Homecoming during the classic period was Elvira

Scratch. One of the events longest running gags, Elvira was the Veterans' Club never very serious candidate for queen. Between 1952 and 1981 Elvira changed her appearance annually but always bore a marked resemblance to one of the

club's more extroverted members in women's clothing. She shaved neither her beard nor her legs, disdained showers, wore a tasteless dress, and was frequently seen with a beer in hand. Her float in the parade was often outlandish. One

year she rode a manure spreader while another year she sat atop a toilet. Beside from her parade floats, she is also remembered for her annual effort to dash onto the football field at half-time to kiss the most senior member of Central's

administration unlucky enough to come within her reach.

A Tradition in Peril

Homecoming experienced many difficulties in the 1960s and early 1970s. As collegiate culture underwent a dramatic change in attitudes and expectations, many students declared Homecoming "irrelevant." Other students complained that it was a

"Greek event" that was of little interest to those who were not members of a sorority or fraternity.

Homecoming experienced many difficulties in the 1960s and early 1970s. As collegiate culture underwent a dramatic change in attitudes and expectations, many students declared Homecoming "irrelevant." Other students complained that it was a

"Greek event" that was of little interest to those who were not members of a sorority or fraternity.

Even when students and alumni attended, much of the celebration's cohesiveness was lost. By 1960 the alumni, perhaps tired of their children's rock 'n' roll, began to hold a separate dance. Many fraternities and sororities followed suit. With so many separate events, the all-campus dance began to lose money. It was abandoned in 1974. Other traditions also began to weaken. The Friday night pep rally was sparsely attended. The traditional bonfire fell victim to a Mount Pleasant city ordinance banning outdoor burning. Although supporters of Homecoming soldiered on, it was clear that the event was in trouble.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s various experiments were attempted to reinterest students in the event. For example, a rock concert was added to the weekend activities. In 1971 the event was radically recast as a "Homecoming Carnival." A carnival came to campus for the week. The parade was canceled. The Homecoming queen was renamed "Miss CMU." Despite these efforts student interest lagged, and it seemed possible that Homecoming would become only a memory.

Modern Era

During the mid-1970s a new consensus emerged that reinvigorated the Homecoming tradition. Without denigrating or denying the importance of student participation, Homecoming became more oriented toward the alumni. The celebration became less about students demonstrating "school spirit" and more about alumni "coming back" to campus.

The parade was resurrected in 1972, but it was usually less elaborate than in the classic era. Friday pep rallies reappeared, sometimes punctuated by fireworks. Gone forever, though, were the bonfires and the "Indian pageantry" of

the earlier era. New events, however, replaced old ones and gave meaning and enjoyment to a new generation of participants. Tailgate parties were first held in the late 1970s. In 1982 a Homecoming king joined the queen. In 1997

the entire concept of a queen and king was revamped. "Campus royalty" was replaced by "Gold Ambassadors," students chosen largely on the basis of their service to the University and community.

Homecoming has gone through many changes in the past seventy-six years, but as it enters the twenty-first century the core reasons that led to the first Homecoming in 1924 persist. Homecoming is still an opportunity for old college

friends to come together, for alumni to meet with today's students, and for the University to put its best face forward. As no other event can, Homecoming binds together the University community.

Homecoming has gone through many changes in the past seventy-six years, but as it enters the twenty-first century the core reasons that led to the first Homecoming in 1924 persist. Homecoming is still an opportunity for old college

friends to come together, for alumni to meet with today's students, and for the University to put its best face forward. As no other event can, Homecoming binds together the University community.