Cultural Engagement

Preparing to go abroad and adjust to your host country and culture is one of the most important parts of your pre-departure “to do” list. This information will help you to start thinking about the cultural engagement experience that awaits you.

- Culture shock and cultural adaption

- Understanding differences in language

- Cultural bias and stereotypes

Culture shock and cultural adaption

Cultural adaptation

Cultural Adaption is the process of learning how to adjust to new and unexpected cultural situations. While being and living abroad, whether for a short time during a faculty-led study abroad program or for a longer time during a direct enrollment program, you will have to manage many changes and adjustments to your daily routines as well as your preconceived notions of life abroad. You are likely to feel some degree of Culture Shock, the anxiety experienced when a person moves into a completely new environment that is often connected with the feelings of lack of direction, not knowing what is appropriate or inappropriate, not knowing what to do, or how to do things in a new environment. Culture shock is completely normal! It is also an opportunity for learning and developing new perspectives as well as a better understanding of oneself, which may stimulate personal growth and creativity.

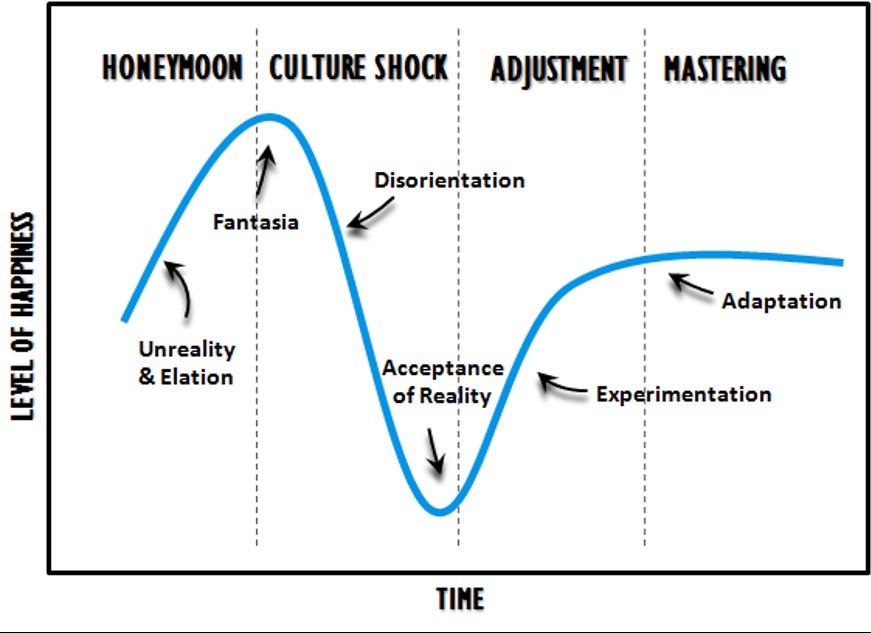

Studies in intercultural education have shown that there are distinct phases of adjustment that virtually everyone who lives abroad experiences. However, the sequence and duration of the stages vary for everyone.

While most people go through each of these stages, individual experiences may differ and one stage may last longer for some, or in some cases be skipped entirely. These stages are:

- Initial Euphoria/Honeymoon: This stage begins with your arrival in the new country and ends when the initial excitement wears off.

- Culture Shock/Frustration: During this phase, people usually take a more active role in their new surroundings. This produces frustration because of the difficulties encountered in dealing with even the most basic aspects of everyday life. Your focus may turn to the differences between the host culture and your home culture, and these differences can be troubling. Sometimes these insignificant problems can get blown out of proportion. This stage is referred to as culture shock.

- Adjustment: When the culture shock phase is over, you slip into the adjustment stage. You may not even be aware that this is happening as you will begin to orient yourself and interpret subtle cultural clues. The culture is gradually becoming familiar to you.

- Mastering/Adaptation: The ability to function in two cultures with full confidence is the fourth stage. Your acute sense of foreignness no longer exists. Not only will you be more comfortable with the host culture, but you may feel a part of it. You may experience a sense of shared fate concerning events in the host country.

- Re-entry phase: When you return home you enter the last stage of cultural adjustment, the re-entry phase. For some people, this can be the most difficult phase of all.

Cultural engagement

Global learning encompasses knowledge, skills, and attitudes and involves a combination of classroom and book-centered learning and experiential learning. One can learn the facts about another culture by reading about them. However, it is through experiential engagement with individuals from another culture that skills and attitudes are developed and nurtured. There are formal and informal ways of engaging and immersing yourself in another culture. Formal ones may be part of your program, such as homestays, language learning, group work with local students, research work with local faculty or students, etc. Informal ways that you can individually undertake to further your cultural engagement with people may range from social media engagement, volunteering, book clubs, English language teaching, exploring food culture, etc.

As you implement your strategies for cultural engagement, whether as part of a program or on your own, here are some ideas to keep in mind:

Understanding differences in language

Language

Language is the primary entry point into any culture. It is the most important way to access and learn about a culture and create connections with other people that have similar viewpoints and interests. Since culture is a “historically transmitted pattern of meanings embodied in symbols,” and words are symbols, accessing language is accessing meaning.

There are various other benefits to learning a foreign language while studying abroad:

- You will cultivate greater awareness and a deeper understanding of other cultures.

- Acquire an indispensable skill that will facilitate your ability to communicate with others and improve your potential for success in your chosen field.

- You may explore career opportunities involving a foreign language.

Signs, symbols, gestures, and manners

The meanings of signs, symbols, gestures, and manners are constituted by the culture in which they are produced. Although a sign, symbol, or gesture may look identical, their meaning will be adduced by the person who ‘reads’ it through their cultural perspective. The situatedness of symbolic meanings may be experienced cross-culturally and even intra-culturally (among members of the same culture).

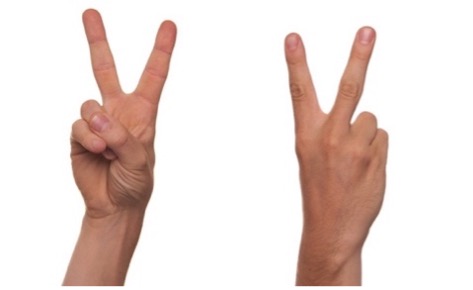

Think about the sign below, which is not limited to any particular culture. However, as a symbol (something that represents or suggests something else), its meaning is culturally produced. What does it mean?

It may be interpreted by many people as representing the number two. In some cultural contexts, the palm out started as wartime “V is for victory” (famously used by Winston Churchill) which morphed into a sign for “peace” in the 1960s that’s still used today. However, with the palm facing in, its meaning is transformed into “F--- you” in the United Kingdom, Australia, and other cultures. Depending on how this sign is used and gestured, it may also carry cruder meanings. In many east and southeast Asian countries, this sign is now used especially by young people in selfies to signify “hi” or “hello.”

As part of intercultural learning, engaging in dialogue with members of the host culture will be extremely important for understanding the meanings of signs, symbols, gestures, and manners to effectively communicate and help you appreciate and respect the diversity of the cultures around the world.

Greetings

Greetings are also culturally constituted. In the contemporary global context, the handshake has become nearly ubiquitous in certain contexts. However, when you travel to a particular country, you will generally be expected to follow the customs and rituals when greeting someone. You will want to keenly observe the nuances of how local people in your destination greet each other and if necessary, politely ask about how to greet if you are unsure.

Some general greeting behaviors to keep in mind:

- A simple “Hello,” “Hi”, or “Hey”

- These are perhaps the three most common phrases for greetings in use around the world today. In many cultures, greetings are expressed not only verbally, but also through an accompanying physical gesture. Different cultures have different customs and greetings.

- Handshaking

- A firm handshake is a popular way to greet in the US and other parts of the world, especially in political or business contexts. However, in some cultures, the handshake may be far more intricate and meaningful than you may assume.

- Bowing

- Bowing is the traditional way of greeting, although there are specific ways to do it in different countries or regions.

- In India, people traditionally greet each other with the phrase namaste (“I honor to you”) or namaskar (“I honor you”) which is accompanied by a common gesture of pressing the palms together with the fingertips facing upward (añjali) and a nod of the head or a bow depending on the status of the person you are greeting.

- In Thailand, people greet each other with the word sawatdee (สวัสดี) followed by polite gendered-particle ka (ค่ะ) for female speakers and krub (ครับ) for male speaker and accompanied by the wai (ไหว้), which involves the placing of two palms together, with fingertips touching the nose. The person should bow their head with their palms pressed together to indicate respect.

- Bowing is the traditional way of greeting, although there are specific ways to do it in different countries or regions.

- Cheek Kissing

- To kiss or not to kiss? That is the question! Cheek kisses are common in many countries across the globe. Depending on the culture and how well the two parties know each other, the number of kisses may range from one to four.

- Spain, Brazil, Germany, Italy, Romania, Turkey, and Tunisia tend to go for two kisses, while Lebanon, Belgium, Egypt, and the Netherlands opt for three. South American spots like Argentina, Chile, and Peru stick with a single kiss.

Gendered norms and greetings

For better or worse, gendered norms are part of the assemblage of culture. In many cultures, males and females have different manners of greeting other people. The gendered and even cultural identity of the greeted individual may influence the greeter’s behavior.

In some cultural contexts, same-sex/gender contact may be appropriate and acceptable, while in others, greetings that involve physical contact with someone of a different sex/gender may be considered inappropriate and unacceptable. If you are unsure about the proper way to greet the host culture, observe and politely ask about how it should be done.

In the context of cheek kisses, gender is an important consideration. In Europe and Latin America, kiss greetings between two women, and between a man and a woman, are widely accepted. A kiss between two men, though rarer, does occur in places like Argentina, Serbia, and Southern Italy. As one might expect, male/female kisses are frowned upon in regions interaction between members of the opposite sex/gender is more culturally strictly regulated.

To tip or not to tip

A perennial question that Americans face when going abroad because tipping is a general practice in the United States that is embedded in the economics of the service industry (waiters, servers, cooks, etc.), but not so in many countries in the world. Why do Americans tip service industry employees? The answer is an economic one: tips are considered part of the wages that service workers earn and report as income to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). In other words, tips are taxable income.

However, regardless of issues around a “living wage,” the minimum income necessary for a worker to meet their basic and essential needs, tipping practices around the world vary. Tipping is also a way to show gratitude for good service, and that value is completely at your discretion. With increasing globalization, tipping customs around the world continue to morph. Indeed, in some places, service industry employees may not expect a tip from a local customer but may expect it from a foreigner. In some countries, a tip is already included in the bill often as a ‘service fee.’ In other countries where the general ideology is that the service staff works for the restaurant as a team and if a customer enjoys their visit, they will return to the restaurant again, tipping may be considered rude.

When abroad, your general practice should be to follow the tipping conventions of your destination country. Observe the locals and follow their lead. You may always politely ask the hotel concierge, hostel staff, or restaurant manager, for example, if you may tip the service staff.

Gastronomy and cultural engagement: Eat bravely while abroad

Like language, food is an integral part of every culture and can serve as another entry point for understanding. Food is a system of signs and symbols in which products and foods are “assembled as a structure, inside of which each component defines its meaning.”[1].

The study of the relationship between food and culture mirrors the complexity of culture itself and can open a window into the economy, history, religion, political society, religion, and other components of culture as well as provide a lens through which to approach contemporary issues such as local and global sustainability issues that intersect food. In the context of global learning and study abroad, openness to new foods is a way to immerse oneself in a new culture through the cultural experience of food– the meanings behind selecting, preparing, and sharing food. Venturing into new foods is venturing into the culture!

Cultural bias and stereotypes

Preconceptions, cultural bias, and stereotypes

Studying abroad provides a unique opportunity not only to learn about another culture but, perhaps more importantly, to critically reflect on and expose your own deeply ingrained preconceptions (idea or opinion you have about something before you really know much about it), cultural biases (interpreting and judging phenomena by standards inherent to one's own culture) and stereotypes (the generalized expectation or belief that you may have about every person o fa particular group) about another culture. Because studying abroad is inherently an intercultural learning experience – learning that takes place in the engagement between members of different cultures – it is also an opportunity for persons of the host culture to learn about you and your culture. Just as you will have preconceptions, cultural biases, and stereotypes, individuals from your host culture will also have them about you.

Stereotypes of Americans abroad

Just as “Americans” perceive a person from a foreign country as a cultural representative, you will be seen as the face of the United States and perhaps the first point of contact with American culture and politics for a person of your host country. In this encounter, both you and your host will be engaged in intercultural learning.

For better or for worse, in our contemporary highly interconnected world, American culture — from TV and movies to politics — has spread throughout the globe. Like all cultural biases and stereotypes, the perception of American abroad is a mixed bag. Americans are often perceived as:

- Wealthy

- Optimistic

- Loud, rude, and boastful

- Hardworking

- Judgmental, moralistic

- Impatient and always in a rush

- Extravagant, wasteful

- Confident they have all the answers

- Politically naïve or uninformed

- Ignorant of other countries

- Disrespectful of authority

- Materialistic

- Generous

- Superficial

As you engage with individuals from your host country, topics like politics, geography, pop culture, crime, etc. in the U.S. will come up in everyday conversations and people will be genuinely interested in what you have to say, in the same way, that you will want to learn about these topics from your host. Indeed, you may find that taboo topics in the US, especially religion and politics, are par for the course in your host culture. Doing some research on your host country's political system (monarchy, constitutional monarchy, etc.) and political categories (Left vs. Right, Liberal vs. Conservative, and shades of the center) will lead to more enlightening and productive conversations.

In the context of these conversations, you should be prepared to answer questions about not only “American culture” but about the complexity of American politics and government. Having a basic understanding of how American government and politics work at the local (city, county), state, and federal levels or why something is culturally relevant or noted, will go a long way to a productive conversation in the context of global and intercultural learning while studying abroad.

[1] Montanari, M. (2006). Food is Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 99.